- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Letters

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Unbearable witness

- Article Subtitle: A new light on Simone Weil

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

In his otherwise bleak 1963 novel The Spy Who Came in from the Cold, John le Carré lets himself have a little fun with the character of Elizabeth Gold. She is an idealistic Jewish woman in her mid-twenties who works in a small library in the London neighbourhood of Bayswater. She is also a member of the British Communist Party. For Liz, however, membership is less a matter of ideology than a token of her moral commitment to peace work and the alleviation of poverty. She is disdainful of her local branch, with its petty ambitions to be ‘a decent little club, nice and revolutionary and no fuss’ – unlike her comrades in the German Democratic Republic (GDR), whose determined struggle against the militarism and decadence of the capitalist West she admires from afar.

- Book 1 Title: A Life in Letters

- Book 1 Biblio: Belknap Press, US$37.95 hb, 384 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

- Book 1 Readings Link: https://www.readings.com.au/product/9780733648533/book-2-michael-veitch--michael-veitch--2023--9780733648533#rac:jokjjzr6ly9m

She is therefore delighted, if a little puzzled, when she receives an invitation to attend a branch meeting of the Socialist Unity Party in the GDR as a delegate from the United Kingdom. Once she arrives in Leipzig, Liz encounters living conditions that are meagre, to say the least: the house of the family with whom she is billeted is dark and cold, the food is ‘poor and most of it had to go to the children’. And yet, for all this, she is happy. With the enthusiasm of an acolyte, she embraces the austerity and derives a kind of solace, if not moral purpose, from the hunger: ‘You felt the world was better for your empty stomach.’

Eventually we learn that the invitation is a ruse, and that Liz is little more than an unwitting pawn in a cynical game. Hardly a surprise. Le Carré was, after all, famously suspicious of idealism. Not that he himself was a cynic. He prized courage, admired loyalty and cunning in equal measure, and graced his greatest literary creation, George Smiley, with a tenacious and endearing decency. But an idealistic young person like Elizabeth Gold is ill-suited to the harsh realities of a rough world. However much we may admire her sincerity and applaud her good intentions, she seems destined to be one of its casualties. Which is why, in the final reckoning, she is more of a cautionary tale than a sympathetic figure.

I can easily imagine readers of A Life in Letters responding in much the same way: with admiration for Simone Weil’s earnestness, with wonder at her precocious intelligence, with a certain bemusement at her moral absolutism. But beneath it all sits the condescending pity we typically reserve for those who have not (yet) made their compromise with the injustice of the world. The correspondence included in this volume, nearly all of it addressed to her parents and older brother, invites just such a response. There is, in fact, a disconcerting dual picture that emerges through these letters.

On one hand, we encounter someone who is passionately concerned with the plight of the oppressed – whether they are factory workers in France, or unemployed Germans on the eve of the National Socialists’ ascension to power, or those on the front line during Franco’s brutal repression of the Federación Anarquista Ibérica. We also encounter someone who is incapable of remaining at a safe distance and expressing their solidarity from afar. Weil insists on placing herself, repeatedly, in situations that are at once perilous and physically demanding. The moral commitment to radical proximity with the afflicted (les malheureux) is inextricably bound up with her philosophical commitment to the notion that truth is not so much known as it is lived. Which is to say, there can be no knowledge without participation.

At the same time, we find someone for whom everything must be provided – from basic cooking instructions (‘How do you make rice?’ or ‘How do you eat bacon? Raw or cooked?’) to a steady supply of books, journals, hairbrushes, money, and paper coffee filters. Weil presents as someone who is unusually inattentive to her own well-being and peculiarly accident prone (while volunteering with the Spanish anarchists, she inadvertently stepped in a pot of boiling oil and had to be taken to a field hospital). In nearly every letter to her parents, Weil assures her mother that she is eating enough food or asks her father to discover the least expensive places for her to eat. Waves of parental concern radiate from the gaps between Weil’s infrequent correspondence. It is little wonder, then, that her parents dutifully comply with the requests she makes and are willing to travel considerable distances in order to rescue their daughter from misadventure. Their desperation is palpable – as is her obliviousness.

As a result, these letters sometimes make for excruciating reading, not least because they lack the consciousness of self-presentation, even of posterity, which distinguishes the writing in Weil’s notebooks and other correspondence. With the exception of the three drafts of an unsent letter to her brother, André, on the mathematical problem of incommensurables and the Greeks’ ‘painful conception of life’, there is simply no comparing this volume with what has already appeared in Seventy Letters (1965) or her epistolary confessions to Father Joseph-Marie Perrin in Waiting for God (1950). In a sense, A Life in Letters is Simone Weil’s unedited self.

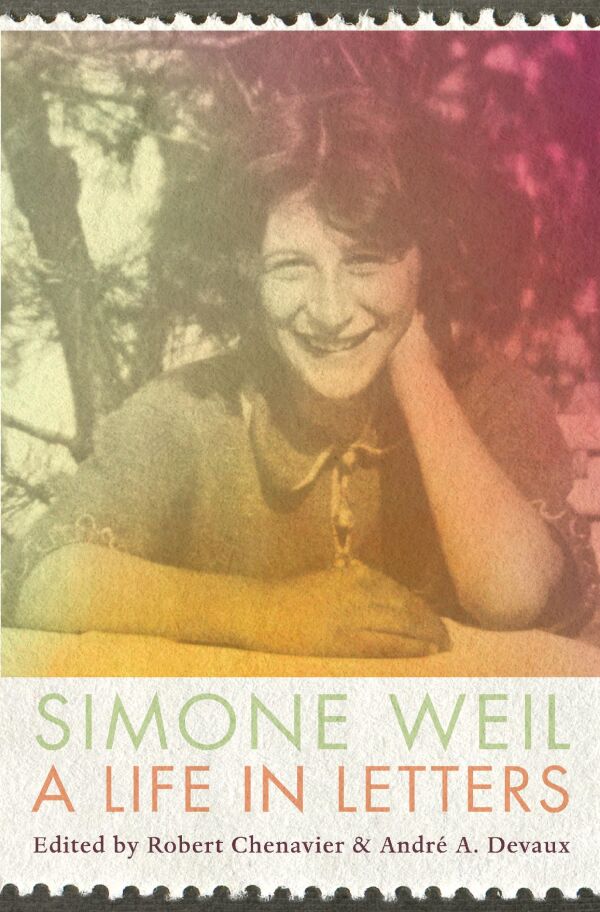

Simone Weil (Danvis Collection/Alamy)

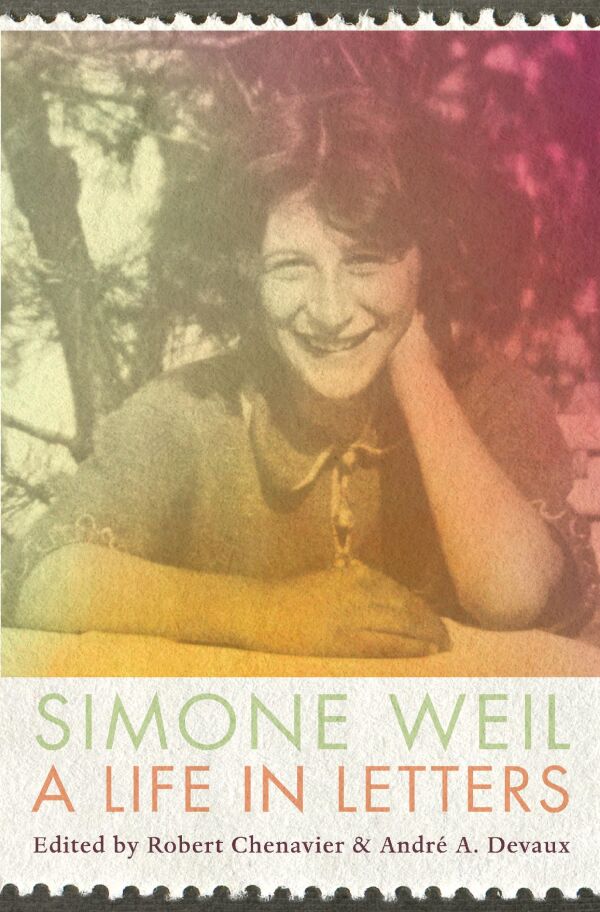

Simone Weil (Danvis Collection/Alamy)

Yet the circumstances of Weil’s premature death – from complications arising from severe malnutrition – would seem to require that we attempt to reconcile these two pictures: her commitment to radical proximity and her habits of self-restriction. I’ll confess that I worry about the tendency to moralise Weil’s troubling relationship with food, however much she herself may have refracted it through the long association that exists in various religious traditions between openness to the divine and forms of denial: of food, of sound or speech, of images, of company, of sex.

Weil was acutely aware that there is nothing inherently virtuous about hunger or silence or solitude. It is rather that the refusal of such transitory satisfactions can help sustain awareness of a longing, an active sense of the soul’s deeper need. So, for instance, she writes to Father Perrin of ‘a silence which is not an absence of sound but which is the object of a positive sensation, more positive than that of sound’.

But, for Weil, there is no form of affliction more fundamental than hunger and no need as basic as food. Hence the recognition of the moral reality of another person begins with a certain attentiveness to their hunger. As she would write towards the end of her life: ‘To know that this man who is hungry and thirsty really exists as much as I do – that is enough, the rest follows of itself.’

In 1942, after she complied with her parents’ wish that she depart Marseilles for New York, and even after she relocated to London later that same year, Weil was overwhelmed with a sense of guilt – that she had consented to live in ‘comfort and security, far from the danger and the hunger’ of those living under German occupation in France. She described herself as growing ‘increasingly and fatally angry’ at herself for having deserted the resistance. In desperation, she dedicated herself to ‘the work’ of establishing a nurses’ corps – of which she intended to be a part – that would parachute behind enemy lines to attend to the wounded. When this plan came to naught, Weil wrote of being cut off from ‘her daily bread’. Denied the work that would morally sustain her life, and unable to refuse the relative safety of London, Weil chose to join the afflicted instead in their hunger.

Should we admire her for her self-destructive choice? There has long been a propensity on the part of Simone Weil’s readers to revere her sanctity, her self-denial. And she herself was conscious of a certain significance stemming from her life, what she would call ‘a repository of pure gold in me that must be passed down’. But this collection of letters is a welcome reminder that admiration is the wrong response to her attempt to bear witness to the afflicted. As she wrote while languishing in New York, the ‘value of a religious or, more generally, spiritual way of life is appreciated by the amount of illumination thrown upon the things of this world’. By venerating Weil herself, we fail to see the way her life focussed attention on the suffering of others. Too many have turned her fragile, fading life into a sort of religious icon; what she meant her life to be was a window through which to see the afflicted as proper objects of love.

Comments powered by CComment