- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Australian History

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Blundering on

- Article Subtitle: Mountford’s expedition reappraised

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Soon after the conclusion of the 1948 Arnhem Land expedition, its leader, Charles Pearcy Mountford, an ethnologist and filmmaker, was celebrated by the National Geographic Society, a key sponsor of the expedition, along with the Smithsonian Institution in Washington DC and the Commonwealth Department of Information. In presenting Mountford with the Franklin L. Burr Prize and praising his ‘outstanding leadership’, the Society effectively honoured his success in presenting himself as the leader of a team of scientists working together in pursuit of new frontiers of knowledge. But this presentation is best read as theatre. The expedition’s scientific achievements were middling at best and, behind the scenes, the turmoil and disagreement that had characterised the expedition continued to rage.

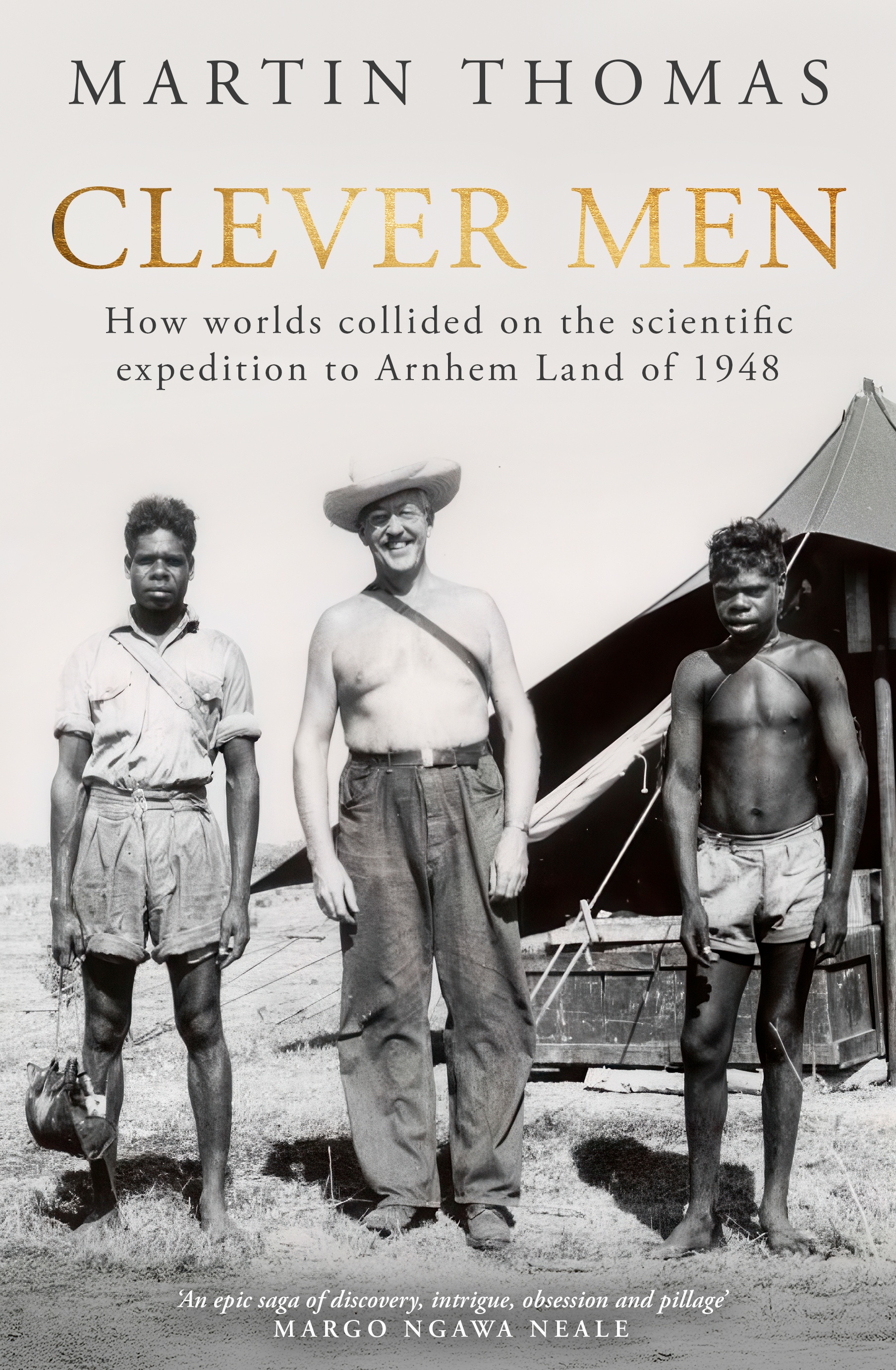

- Book 1 Title: Clever Men

- Book 1 Subtitle: How worlds collided on the scientific expedition to Arnhem Land of 1948

- Book 1 Biblio: Allen & Unwin, $36.99 pb, 496 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

- Book 1 Readings Link: https://www.readings.com.au/product/9781761069321/clever-men--martin-thomas--2025--9781761069321#rac:jokjjzr6ly9m

Mountford had been entirely unsuitable to take on a leadership role. He had no prior experience in leading an expedition; he was disorganised and seemingly either resistant to or incapable of making difficult decisions. Among his many missteps was a failure to organise for the expedition’s equipment to be transported from Darwin to its first Arnhem Land stop in Groote Eylandt. Instead, he suggested that the expeditioners proceed by air ahead of their stores of food, tobacco, recording equipment, and more. At last, he purchased a cheap barge from the navy – cheap because it had been declared unseaworthy – that finally arrived at Groote after a tumultuous voyage of over seven weeks. This troubled beginning did not necessarily affect Mountford’s own research; he had ensured that the gear he needed for that was on the plane. This apparent selfishness and willingness to subordinate others’ research interests to his own prompted ongoing complaint and frustration among his fellow researchers and their subjects.

The expeditioners’ quiet (and sometimes not so quiet) expressions of these grievances recur throughout Martin Thomas’s historical ethnography of their search for knowledge. Clever Men follows its fifteen men and two women to Groote Eylandt, to Yirrkala, and then on to Gunbalanya, its story animated by Thomas’s remarkable attentiveness to the interpersonal dynamics of the group. He describes the expedition in meticulous detail, signalling extensive and collaborative research conducted over roughly two decades. We learn how much (and how loudly) some of its members snored, who of the men seemed the sleaziest, and how their petty prejudices emerged and were felt.

This kind of knowledge produces new questions. How can a group so focused on its internal relationships – and so dissatisfied by them – learn anything about others? Perhaps they can’t; confronted by difference, the expeditioners were often mystified. Sometimes they sought to sublimate this confusion by focusing on collecting data that measured relative superficialities, like the distance people could throw a spear, for instance. At other times they simply blundered on in a state of ignorance.

Reading Clever Men, one senses Thomas’s frustration with the expedition’s failure to produce workable knowledge of its subjects. Writing of the joking songs composed and sung by expedition members in moments of rest or levity, he describes their ‘puzzling … cultural whiteness’, noting that ‘Arnhem Landers are barely even mentioned in the lyrics’. These were songs about the expeditioners themselves, suggesting an inward preoccupation that inflected both work and play.

This navel-gazing is problematic for a historian seeking to examine the significance of the expeditioners’ encounters with the people of Arnhem Land. Thomas addresses this by working alongside today’s descendants of the Arnhem Landers on the expedition, arguing that studying the expedition’s materials alongside the ‘true experts’ (perhaps the true clever men) is ‘essential to any holistic understanding of the expedition’.

Among the few Aboriginal people with whom the expeditioners seem to have formed a close relationship was Gerald Blitner, whose skill, knowledge, and generosity rendered him indispensable as a broker with the Anindilyakwa of Groote Eylandt. Yet being the son of a white German father, Blitner was far from the untouched ‘primitive’ the expeditioners were looking for, and his contributions were erased from the text of their reports. Thomas restores Blitner to the historical record and ensures his voice is audible to us today.

If their focus on performing as expeditioners hamstrung Mountford’s men from learning much new about the people of Groote Eylandt, Yirrkala, and Gunbalanya, what they could at least do was collect stuff. They accumulated tons of materials, including a wide range of animal specimens, few of which represented any new scientific discovery. They requested cultural objects and stories, took thousands of photographs, shot hours of film, and commissioned bark paintings (Mountford acquired nearly 500) and other material culture.

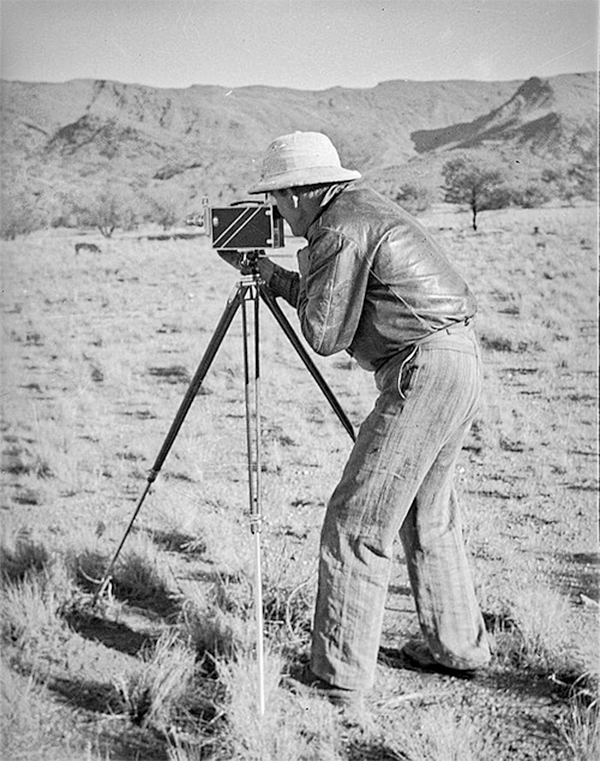

Charles Mountford, Mann Ranges, 1930 (photograph by Bessie Mountfod via Wikimedia Commons)

Charles Mountford, Mann Ranges, 1930 (photograph by Bessie Mountfod via Wikimedia Commons)

Perhaps most notoriously, some of the expeditioners took ancestors’ bones, knowing full well that this practice caused great trouble and anger; they prioritised a mania for collection over local sensibilities. The recent repatriation of stolen bones to Gunbalanya was the subject of Thomas’s 2018 film, Etched in Bone, which exposed the theft carried out by Frank Setzler, Head Curator of Anthropology at the Smithsonian and deputy on the expedition. In the film, Setzler noted many burials while exploring a cave at Injalak. He affected a lack of interest in the bones while his two Aboriginal assistants were present. While they slept, Setzler took his chance, both to steal the bones and to perform, filming himself ‘discovering’ then collecting packages of bones, unwrapping and then boxing them to take to the Smithsonian. We learn in Clever Men that his ‘repellent yet compelling’ recordings present a practiced performance; out-takes reveal a series of attempts at acting the scene, discovering and rediscovering the bones in the guise of, alternatively, a scientist, a madcap explorer, and more. These were undoubtedly well rehearsed; Setzler had procured bones at previous stops, accumulating so many that he only ceased when he ran out of boxes.

Margaret McArthur’s work is less well known and certainly less notorious. Her capacity to conduct meaningful anthropological research positions her as perhaps the most exceptional figure among the expeditioners. One of only two women on the expedition, she tended to remain socially aloof, her companions’ sexism often excluding her from their circle of self-regarding fraternity. Perhaps because she was somewhat of an outsider, she generated actual, valuable knowledge. McArthur’s work – in partnership with Fred McCarthy of the Australian Museum – on childcare, labour, and diet in the bush economy revealed Bininj work patterns, deep environmental knowledge, and ‘affluence’ – a genuinely original contribution to anthropological knowledge.

Overall, Thomas shows, the expedition engaged in a solipsism characteristic of many colonial adventurers who sought to make their name by discovering the habits of a primitive Stone Age people, a species of bug, or something ‘new’. Maybe this is emblematic of an expedition and its practice as a self-actualising masculine quest. It was never really about the locals they encountered, who confounded the travellers’ expectations in ways that they could not quite come to terms with. The expedition was about the men who fancied themselves expeditioners and fashioned themselves accordingly.

Clever Men changes direction in the final chapters. Up to this point we follow Mountford’s itinerary; now the expeditioners recede to the margins and the people of Gunbalanya today are freed to engage directly with the legacy of the expedition, with their records of ceremony, and with the return to Country of stolen bones. In the ideas and stories of Thomas’s collaborator Bininj leader Jacob Nayinggul, for instance, we are presented with another mode of engaging with the world: one characterised by respect, careful consideration, and a sense of responsibility. It is hard to resist comparing this sensibility with those of Mountford or Setzler, with their cavalier and often duplicitous research practice. Clever Men provokes reflection on these dispositions. A valuable contribution, it will be of interest to those curious about the kinds of men who embarked on anthropological expeditions, how they performed their roles, and the ways we might reckon with and take responsibility for their legacies.

Comments powered by CComment