- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Survival of the spitefullest

- Article Subtitle: An idiosyncratic allegory

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

‘Lapvona dirt is good dirt,’ say the inhabitants of the titular medieval fiefdom in which Ottessa Moshfegh’s fourth novel, Lapvona, takes place. While the description refers to Lapvona’s rich soil, it could easily be an artistic statement. Moshfegh has long been an author concerned with physical and existential waste, and a vector for protagonists who alternately wallow in and renounce their own muck – from the virginal twenty-four-year-old narrator of Eileen (2015), who abuses laxatives and can’t bear to contemplate her own genitals, to the acerbic sleeping beauty at the heart of her most renowned work, My Year of Rest and Relaxation (2018), to Vesta Gul of Death in Her Hands (2020), a hermetic widow obsessively investigating an imaginary murder. The post-plague abjection of Lapvona is therefore fertile ground for Moshfegh to explore the horrors of embodiment that have previously defined her work.

- Article Hero Image (920px wide):

- Article Hero Image Caption: Ottessa Moshfegh (photograph by Krystal Griffiths/Penguin)

- Alt Tag (Article Hero Image): Ottessa Moshfegh (photograph by Krystal Griffiths/Penguin)

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Laura Elizabeth Woollett reviews 'Lapvona' by Ottessa Moshfegh

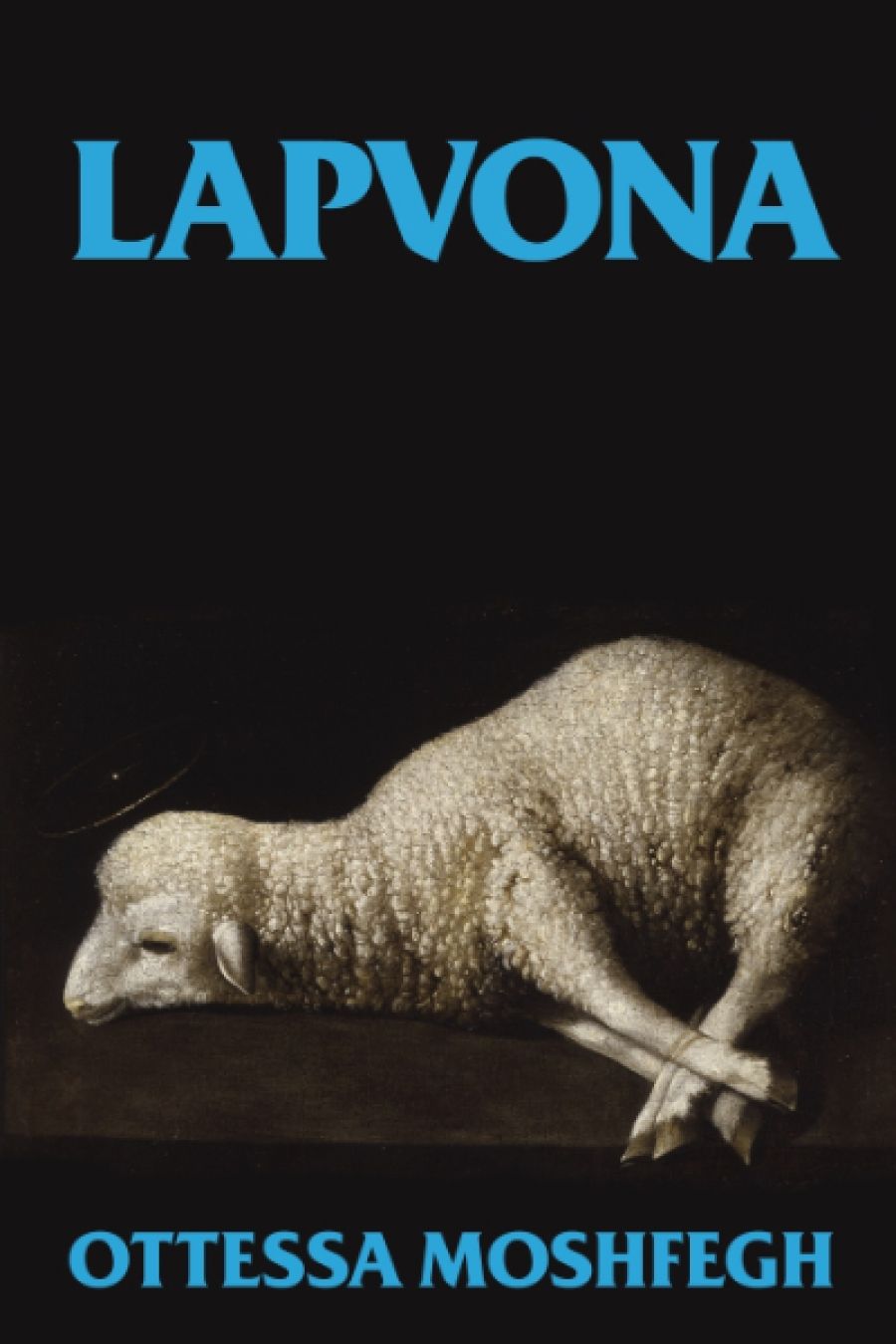

- Book 1 Title: Lapvona

- Book 1 Biblio: Jonathan Cape, $32.99 hb, 304 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/ZdMVNk

Moshfegh’s settings have always been imaginative landscapes, first and foremost. ‘I just want to see the edge of the building, and then I want to go build it myself,’ she stated in a 2018 interview with The New Yorker, explaining her distaste for in-depth historical research. Accordingly, Lapvona is both idiosyncratic and allegorically vague. There are pastures where shepherd Jude and his son Marek graze their ‘babes’. There are dark woods, home to ancient wetnurse, Ina. There is a lake, which transforms into a Boschian hellscape come summer’s drought. There is a moated manor uphill, where overlord Villiam shuns his subjects’ suffering. There are incestuous bandits. There are tall, fair ‘Northerners’ from rival fiefdom, Kaprov. Vegetarianism is godly. Cannabis grows. Milk springs from wizened breasts. Humans see through horses’ eyes. Perversion is quotidian. Death is a release. So far, so Moshfegh.

Where Lapvona differs most from Moshfegh’s other books isn’t its quasi-historical setting (her 2014 novella McGlue dealt with a murder aboard a nineteenth-century ship), nor its forays into the surreal (she is best known for a book about a woman sleeping for a year). Lapvona’s greatest deviation lies in its eschewal of the entrenched first-person storytelling mode that has become synonymous with Moshfegh since the mainstream success of Eileen. Here, she trades the solipsism of her (primarily disaffected and female) narrators for a roving perspective, reminiscent in scope of Damon Galgut’s The Promise (2021). The plot is theoretically grounded by thirteen-year-old shepherd-boy Marek – a disfigured child of rape, incest, and paedophilia – and the impulsive crime that leads to his replacing golden boy Jacob as Lord Villiam’s son and heir. Yet this plot feels secondary to Moshfegh’s experimental head-hopping, and Marek is (beyond his initial rebellion) a phlegmatic character, given too little space or charisma to be a compelling anti-hero.

Of course, Marek’s lack of charisma is significant: power doesn’t necessarily belong to the charismatic, nor does the poverty into which Marek is born render him more capable of benevolent leadership than his princely rival Jacob, or Villiam himself – a limp, giddy, eternally bored degenerate, so detached from reality that his own son’s corpse seems to him like a work of theatre, ‘staged for his private amusement’. Power and who wields it, in Lapvona, is mostly a genetic lottery. Those like Marek who snatch at life above their station, or who like Jude and Ina survive in spite of famine, do so out of pent-up ressentiment or blind hunger. Nobody is particularly intelligent, caring, or attached to existence, and the few who are motivated by passion – Jacob, with his penchant for adventure, or his mother, Dibra, in love with horseman, Luka – appear doomed. Survival of the spitefullest is Lapvona’s natural law.

For all the horrors that Moshfegh inflicts on her characters, and they on each other, she is evidently fond of them. She has fun untangling their faiths, foibles, and perversions, and finds humanity where others may not. Take Villiam’s eventual slide into depression, when he is unable to withstand his own bottomless need for stimulation. Or self-flagellating abuser Jude, so lacking in insight that he ponders over his abjection: ‘Hadn’t he been a good man? Hadn’t he prayed enough? Hadn’t he lashed himself correctly? It never occurred to Jude that the capture and detention of Agata … was anything but his rightful duty as a man.’

However, Moshfegh’s enjoyment of her characters only amounts to so much. It is difficult to read Lapvona without thinking of what’s come before, and what might have been. Lapvona’s conceit recalls the Marquis de Sade’s unfinished opus The 120 Days of Sodom, which follows the months-long orgy of four libertines and their harem of victims in a secluded castle. As in 120 Days, violence and boredom are bonded in Lapvona; characters are flattened by their overarching damnation, and readers are likely to become desensitised by the sheer excess of human waste. Yet the incompleteness of 120 Days ultimately resensitises, as Sade’s storytelling gives way to lists of victims’ names, methods of torture and murder, leaving a lasting impression of violence without form and of vanity of giving form to violence. Lapvona, by contrast, is controlled. Moshfegh’s elegant, droll prose seems removed from the universal chaos she’s depicting. There is no culmination to the action, no catharsis, no great spiritual growth or death – just a frieze of well-drawn weirdos, loosely connected by setting and lineage. For all its bloodshed, Lapvona can feel bloodless.

If Moshfegh wanted to write another My Year of Rest and Relaxation, centred on the psychology of a single Lapvonian, she could have done so; it might have been a more engaging novel. That Moshfegh attempts something broader here is ambitious. That Lapvona is less than the sum of its parts shows that Moshfegh is still learning the lay of the land. Good dirt is good dirt, but it doesn’t always yield.

Comments powered by CComment