- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Memoir

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Tit for tat

- Article Subtitle: The conflicted life of Sandra Willson

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

What could compel a woman to murder a complete stranger? This is the obvious question posed by Sandra Willson’s execution-style murder of Sydney taxi driver Rodney Woodgate in 1959 following the traumatic end of her lesbian relationship with a fellow trainee psychiatric nurse. It is something that Willson grapples with in her searing memoir, which she wrote over several decades. Posthumously edited by historian Rebecca Jennings, it joins one of a small group of books that provide a first-hand account of the criminalisation and institutional repression of lesbianism and gender non-conformity in mid-twentieth-century Australia.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Sam Elkin reviews 'Between Me and Myself: A memoir of murder, desire and the struggle to be free' by Sandra Willson, edited by Rebecca Jennings

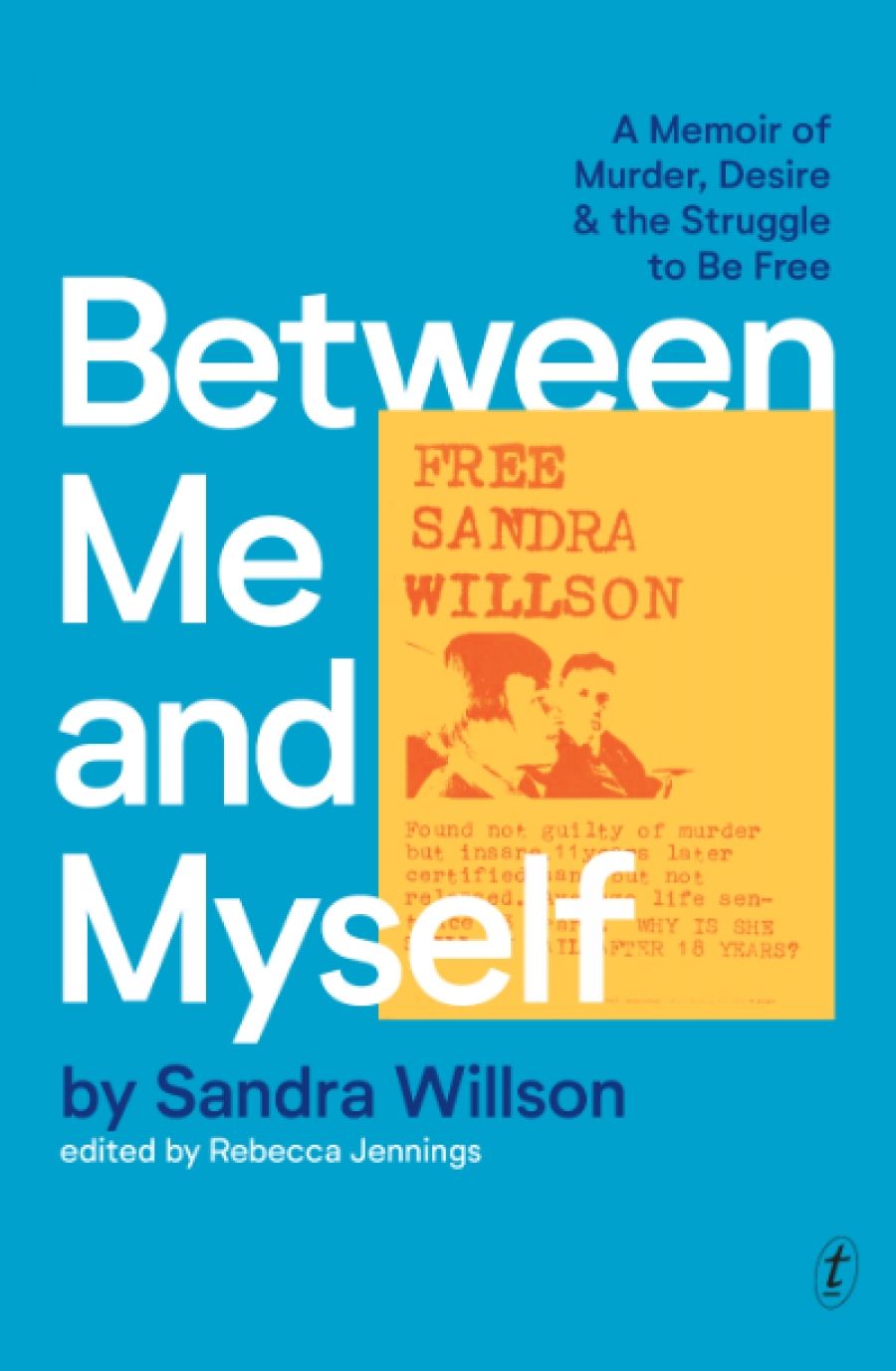

- Book 1 Title: Between Me and Myself

- Book 1 Subtitle: A memoir of murder, desire and the struggle to be free

- Book 1 Biblio: Text Publishing, $34.99 pb, 326 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/RyM0Ga

When Willson died in 1999, her memoir was thought lost. Luckily, a friend of hers bequeathed it to Jennings after she gave a paper on Willson’s legacy at an academic conference in Sydney. Jennings describes the arduous task of turning Willson’s 150,000-word manuscript, written at different periods of her life, into a highly readable book.

The result is a compelling account of the devastating impact of institutional homophobia, family violence, sexual assault, and the incarceration of women in New South Wales. As to the question of why she killed, Willson herself posits a somewhat strange explanation, saying:

[t]he only choice that was left to me was to pick out a single member of society, as it was society itself that would bear the blame for the way that it had taken from me all that I had ever loved. Barbara, and now Norma! I had lost, and now society was to lose. Tit for tat.

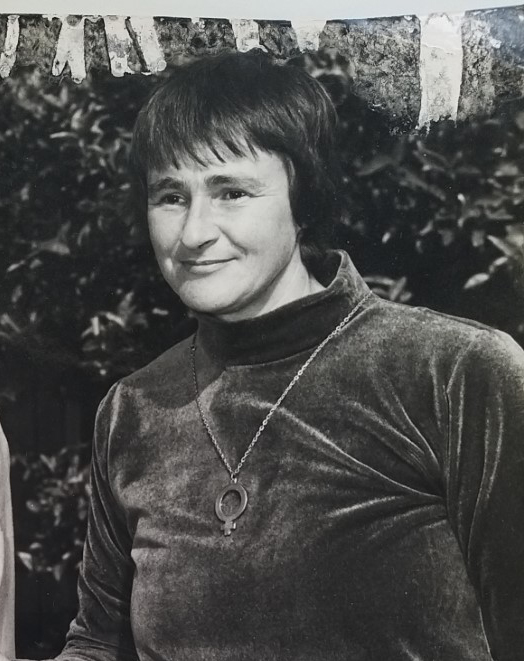

Sandra Willson (photograph via Text Publishing)

Sandra Willson (photograph via Text Publishing)

Her broader life story gives the reader some extra clues. Willson begins with an account of her early life as a masculine, gender non-conforming woman in a British-Australian, working-class family plagued by conflict and profound emotional avoidance. A tomboyish loner, Willson was sexually assaulted by predatory adults and then ostracised and bullied by other children because of her gender presentation. At the age of fourteen, she was brought before the Children’s Court and detained at Parramatta Girls Training school after attempting to initiate a relationship with an adult woman.

Willson’s story presents, in vivid detail, an account of the many ways that Sydney girls reformatories sought to control young omen’s bodies, including forced gynaecological examinations to detect pregnancies and venereal diseases, and the widespread use of the powerful anti-psychotic drug Largactil to suppress unruly behaviour in troubled adolescents.

Upon Willson’s release, she meets other lesbians and briefly finds work at a metal workshop, ‘passing’ as a young male by wearing a suit and deepening her voice. She falls in love with another woman and they begin living together as ‘man and wife’ in Bondi. The romance comes to a disastrous end when the police are tipped off, and she is sentenced again for ‘Being Exposed to Moral Danger’. After harming herself, she is sent to a psychiatric hospital in Gladesville. Aged eighteen, Willson then trains to become a psychiatric nurse herself, and begins a relationship with a fellow trainee. The end of that relationship was the precursor to the murder.

Willson is arrested and ultimately found not guilty on the grounds of insanity, for which she is detained indefinitely, known at the time as being held ‘at the Governor’s pleasure’. During this time, she begins writing her memoir. Willson writes about grappling with the ethics of even writing a memoir at all due the pain it would likely cause her victim’s family. Although the writing process caused her immense anguish, her desire to tell her story was so powerful that at one point she even escaped from the psychiatric hospital to post her manuscript to Penguin.

Willson’s insights into her own behaviour are fascinating. From her reflections on her possessive, demanding behaviour towards her first live-in partner to her grappling with the shifting psychiatric diagnoses she receives over the years, Willson depicts a wilful, lively individual who is prepared to interrogate her own values and behaviour in order to heal and to live a life free from violence. The final chapters provide an account of Willson’s efforts to set up the first halfway house for women leaving prison in New South Wales in conjunction with ‘Women Behind Bars’.

Editing and publishing a memoir about complex and contested topics is not straightforward. Jennings, a historian, understandably footnotes a number of moments throughout Willson’s text where her version of events strays from the official account held in her official prison and psychiatric files. While these footnotes give the book an interesting alternative perspective, they also destabilise Willson’s authority as a reliable narrator of her own life. One wonders how Willson would have felt about the incorporation of these official records into the final text, had she lived to see her memoir published.

An intriguing question about Willson’s gender expression is not addressed by Jennings in her introduction or afterward. Willson describes herself as ‘looking like a man in drag’ in women’s clothes and prefers to wear suits, even gaining employment as a male at a metal workshop. These scenes are reminiscent of Leslie Feinberg’s trailblazing semi-autobiographical transgender novel Stone Butch Blues, first published by Firebrand Books in 1993. Might Willson have experienced her gender differently had she been born in an era of trans and non-binary identities?

So much in Willson’s memoir will fascinate those interested in the history of homosexuality, gender studies, criminology, and psychiatry. It reveals the deep psychological impact of sexism and homophobia, and how quickly a vulnerable person’s life can unravel. As one of the few first-person accounts of the systematic social exclusion of lesbians in twentieth-century Australia, Sandra Willson’s memoir is precious.

Comments powered by CComment