- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: The spirit of place

- Article Subtitle: A timely antidote to cultural amnesia

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

‘In Sydney if you have something to say you hold a party; in Melbourne you start a journal,’ quipped the poet and critic Vincent Buckley in 1962. Buckley was an acute, astringent observer of the literary culture of the two cities. An outsider in both, he recognised Melbourne’s characteristic voice – ‘earnest, do-gooding, voluble’ – in the leftish humanism of its leading literary journals, Clem Christesen’s Meanjin and Stephen Murray-Smith’s Overland. Not for Melbourne the anarchic frenzies of the Bulletin, the Sydney Push and Oz. While Sydney had the best poets, Buckley contended that the southern capital had the most influential opinion makers.

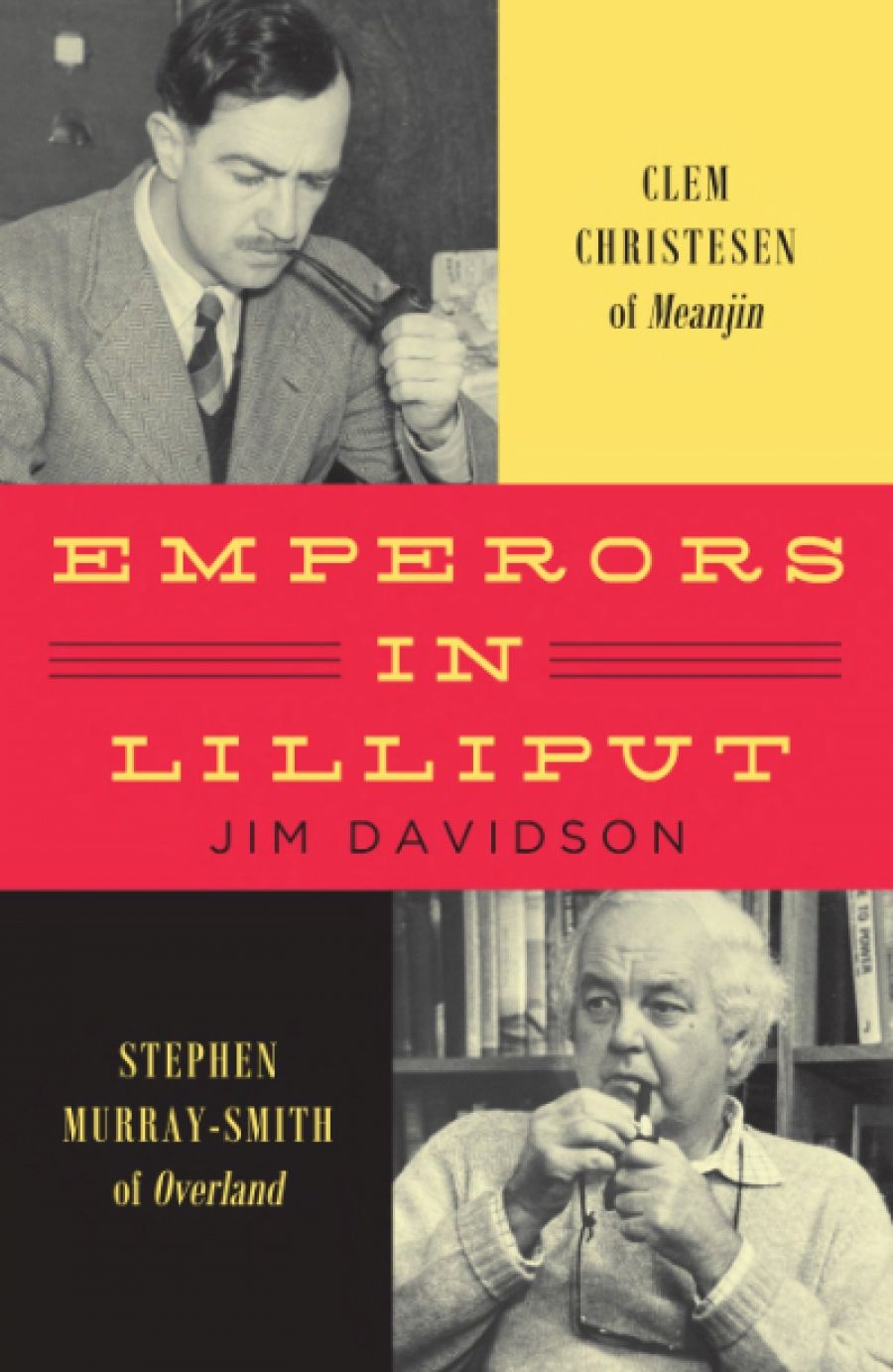

- Article Hero Image (920px wide):

- Article Hero Image Caption: Clem Christesen and Stephen Murray-Smith with Kylie Tennant at Monash University, 1975 (University of Melbourne Archives, Baillieu Library)

- Alt Tag (Article Hero Image): Clem Christesen and Stephen Murray-Smith with Kylie Tennant at Monash University, 1975 (University of Melbourne Archives, Baillieu Library)

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Graeme Davison reviews 'Emperors in Lilliput: Clem Christesen of Meanjin and Stephen Murray-Smith of Overland' by Jim Davidson

- Book 1 Title: Emperors in Lilliput

- Book 1 Subtitle: Clem Christesen of Meanjin and Stephen Murray-Smith of Overland

- Book 1 Biblio: The Miegunyah Press, $59.99 hb, 478 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/n1MDV6

Emperors in Lilliput is the third of what Jim Davidson sees as a ‘loose trilogy’ of biographies of representative Australian cultural figures. The first two, Lyrebird Rising (1994) and A Three-Cornered Life (2010), approached Australia from the outside, through the lives of long-time expatriates Louise Hansen-Dyer, creator of the Paris-based recording company L’Oiseau-Lyre, and Keith Hancock, a distinguished historian of empire who returned to Australia in his late fifties. Christesen and Murray-Smith, by contrast, lived almost their entire lives in Australia and devoted them to the creation of a homegrown literature.

In tracing their careers, Davidson tackles one of the perennial themes of Australian history: the attempt of a settlement society to make its culture. While Davidson acknowledges earlier cultural nationalists, such as J.F. Archibald, Joseph Furphy, P.R. Stephensen, and the Jindyworobaks, his subjects were the characteristic product of a new chapter, marked by World War II and the popular front against fascism, when the left reawakened to the mobilising force of national myths and traditions. That impulse persisted beyond the war as left-liberals and radicals, including Christesen and Murray-Smith, sought to erect a bulwark against the effects of American consumerism, pop culture, and McCarthyism.

Davidson’s two emperors were a familiar presence when I arrived on the University of Melbourne campus in the late 1960s. Murray-Smith, a Falstaffian figure in corduroy trousers and houndstooth jacket, looked and sounded more like an English squire than an ex-communist activist, although, as I found, his manner belied his essential egalitarianism. In my mind’s eye, the dapper, goatee-bearded Christesen, often accompanied by his pretty Russian wife, Nina, was a less conspicuous figure, often sitting among his congenials – ‘the grey men’, my colleague John Foster called them – in a corner of the University House dining room.

Meanjin and Overland drew on kindred streams of left-liberalism and struggled, at times, to differentiate themselves. The circles of contributors and supporters overlapped – Geoffrey Serle was a key figure in both – and there was a reluctance to admit that they might actually be in competition. Each journal was the peculiar creation of its editor. Christesen, a journalist, had founded Meanjin in Brisbane in 1940 – its name, literally ‘spike in earth’, is the Aboriginal name for the Brisbane region – and he brought it to Melbourne in 1945. There he remained for the next forty years while, according to Davidson, never quite feeling at home. He was probably a better editor than Murray-Smith, with a more critical eye, wider literary sympathies, as well as superior and more fastidious design and production talents. He attracted a more diverse stable of writers and built a slightly larger circulation.

Overland, established in 1954, was a legacy of Murray-Smith’s work on behalf of the Realist Writers’ Group and its journal, Realist Writer. When he left the Communist Party after the 1956 Hungarian Revolution, the newly formed Overland and its vital circulation list came with him. Even then, Overland only slowly widened its sympathies beyond the explicit Marxism of its original charter. While aspiring to recruit new working-class writers, the magazine’s most regular contributors continued to be communists or ex-communists – among them John Morrison, Judah Waten, Frank Hardy, and David Martin. Compared with Meanjin, it was more collaborative, informal, and improvised in spirit and style. Murray-Smith’s regular column ‘Swag’ was its authentic voice. While Davidson acknowledges Christesen’s as the greater achievement, he clearly finds Murray-Smith the more interesting biographical subject.

What united and sustained both emperors was their dedication to the creation of an authentic, self-conscious national culture. As Davidson demonstrates, this was a heroic, selfless, sometimes quixotic venture. Spurned by the Commonwealth Literary Fund, then under Menzies’ tight control, and only drip-fed by their institutional supporters, such as the University of Melbourne (Meanjin) and sympathetic trade unions (Overland), Christesen and Murray-Smith were often forced to dip into their own pockets to keep their publications afloat. By 1972, Davidson estimates, Christesen had invested $40 000 of his own money ($400,000 in today’s money) in the journal. Like Ulysses, the two editors were irrevocably bound to their mastheads. While they might lament their burden – and Christesen’s ‘Clemmiads’ were notorious – neither helmsman could or would easily surrender his command.

As Christesen’s successor, Davidson consciously resists the temptation to allow ‘recently gained perceptions’ to shape his narrative. But at page 307, his voice abruptly shifts from the third to the first person. In 1974, then a young and untenured historian, he accepted the editorship of Meanjin, only to discover that the incumbent effectively refused to relinquish it. ‘I was being cast as cabin boy to Clem on his tempestuous voyage,’ he recalls. His chapter on the affair, ‘Power Struggle in the Clemin’, is a candid, sometimes hilarious, ultimately poignant story.

Emperors in Lilliput is much more, however than a portrait of two imperious editors. Davidson draws on what must surely be the largest literary archive in the country – more than 1,000 boxes of manuscripts and correspondence – to construct an intimate and group portrait of the postwar Australian literary community. With characteristic wit and flair, he captures their personalities and offers fresh insights into their writing. Well-known figures such as Vance and Nettie Palmer, Judith Wright, Vincent Buckley, Brian Fitzpatrick, and Dorothy Hewett appear in a new light. Perhaps the most rewarding passages, however, are Davidson’s touching portraits of lesser-known figures, such as Overland ’s poetry editor Laurence Collinson, Meanjin in-house critic Arthur Phillips, Murray-Smith’s closest friend and ally Ian Turner, and, especially the two women, Nina Christesen and Nita Murray-Smith, without whose emotional, intellectual, and material support surely neither man, nor his magazine, would have survived.

By the late 1960s, the two journals were running out of steam. Their editors were ageing, but so too was their conception of national culture. When they looked beyond Australia, it was always to London rather than New York and Paris, and to high culture rather than the new forms of popular culture that were to flourish during the 1970s. It was another war, the Vietnam War, which effectively killed off the radical nationalism that had sustained the two magazines for more than three decades. In charting their history, Davidson illuminates not only the circumstances that made and unmade them, but what they gave us and what would have been lost without them.

‘The important determinant of any culture is the spirit of place,’ Christesen once wrote. The little magazines, and the cultural nationalism they espoused, were a product of that spirit of place. Localism is not dead, but as Davidson perceives, is everywhere under threat from a pervasive and debilitating globalism: ‘The country is in danger of losing its memory, if not its mind,’ he concludes bleakly. Yes, but his book is a powerful and timely antidote to that amnesia.

Comments powered by CComment