- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: History

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: ‘Linger with the voids’

- Article Subtitle: Examining the relationship between past and present

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

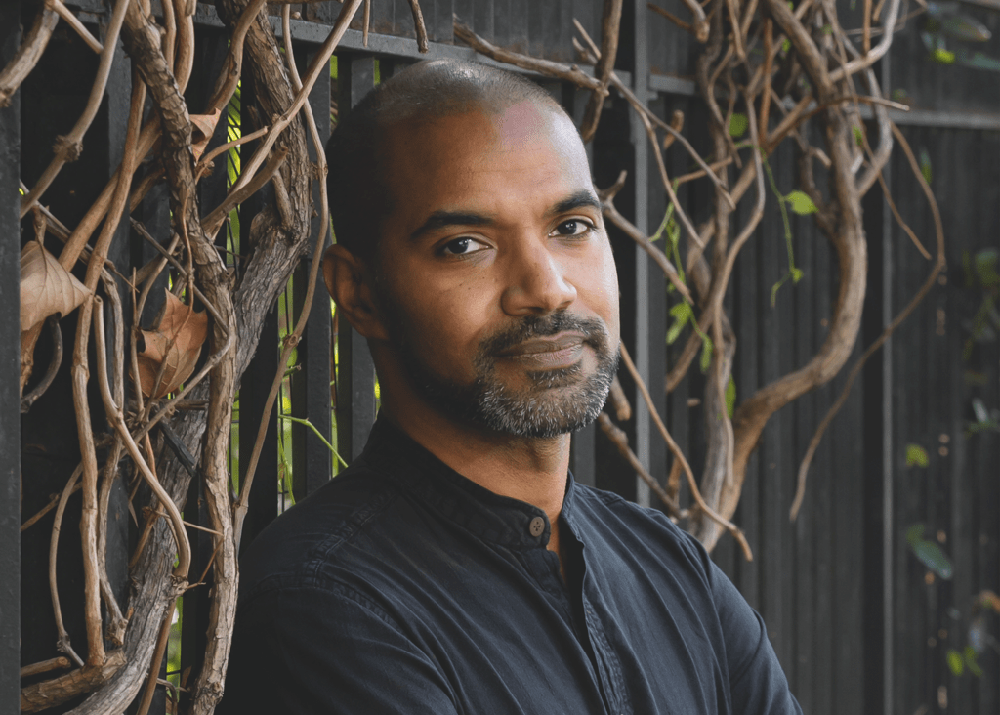

‘To fully understand why the shadow of slavery haunts us today, we must confront the flawed way that it ended.’ This premise guides the third book of Kris Manjapra, a Bahamian of African and Indian descent and history professor at Massachusetts’s Tufts University. As Manjapra invites us to see, the ‘voids’ in his family’s history reflect the pernicious afterlife of five hundred years of Atlantic slavery; his loss just one of its manifold legacies.

- Article Hero Image (920px wide):

- Article Hero Image Caption: Kris Manjapra (photograph by Beowulf Sheehan/History Extra)

- Alt Tag (Article Hero Image): Kris Manjapra (photograph by Beowulf Sheehan/History Extra)

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Georgina Arnott reviews 'Black Ghost of Empire: The long death of slavery and the failure of emancipation' by Kris Manjapra

- Book 1 Title: Black Ghost of Empire

- Book 1 Subtitle: The long death of slavery and the failure of emancipation

- Book 1 Biblio: Allen Lane, $45 hb, 253 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/oeMQJb

This book is for those who want clarity on the direct relationship between the past and the present. Some would say that is what all history should do; many historians would not. Manjapra is particularly concerned with the interesting relationship between pre-emancipation and post-emancipation societies. His contention is that Atlantic slavery was a war and that policies of so-called emancipation actually extended it. Was this inadvertent? Not at all, Manjapra argues: emancipatory acts were written and governed by slave-owning castes and their associated beneficiaries in the fields of law, industry, finance, and governance, to prolong their profiting from slavery.

Such claims might appear counter-intuitive. If so, read on, for Manjapra is the first to tell you that there are good reasons why many read ‘emancipation’ as ‘freedom from slavery’, not least because it literally means it. As Manjapra shows, in many slave societies emancipation acted as something like modern-day marketing or greenwashing, maintaining the status quo while professing to do something radically different.

Unlike many historians, Manjapra ranges across European slavery empires. Over six chapters, he provides a chronological, if broad-brushed, account of emancipation in the American North, Haiti, the British Caribbean, and Africa. This leaves, in a relatively short book, little space for localised, contextualising detail. Yet the book’s brevity calls to a general readership, as does its geographical and temporal reach.

It means also that Manjapra can investigate structural and rhetorical patterns in the enslavement of Africans. He is most interested in the common and unique ways European societies extended captive labour in the face of sustained and strong African resistance, as well as domestic moral shaming of chattel slavery, particularly by white women. Manjapra’s argument here is that tactics to maintain slavery in the face of such challenges were circulated among European and American powers in language as mild (gradualism, amelioration) as it was deceptive.

The original model for pan-Atlantic ‘gradualism’ was the Act for the Gradual Abolition of Slavery 1780, which stipulated that all those living under slavery would remain so for the rest of their lives. It was only when enslaved children born after 1780 reached adulthood that emancipation in Pennsylvania meant liberty. In the years following this act, strategies to subvert freedom in the name of freedom multiplied across the Atlantic and included periods of ‘apprenticeship’, sometimes more brutal than slavery itself, and laws requiring that the enslaved pay debts of freedom to their enslavers.

Unimaginable, unquantifiable suffering was inflicted on enslaved people by supposed anti-slavery societies, often in the name of acquiring their freedom. Black Ghost of Empire seeks to debunk the notion that the American North was opposed to slavery. Manjapra details the ways slavery underpinned the economic and territorial growth of the North. After it was outlawed, he goes on to point out, slavery in the American South was sustained by northern merchants, manufacturers, investors, law makers, and law enforcers. How otherwise could Black children in New York be repeatedly stolen from their families and sold to southern slavers?

When, after the Civil War, President Andrew Johnson sat down with Black male delegates from twelve states, including Frederick Douglass, to explain that reparations would be going to southern planters, not the formerly enslaved, Johnson insisted that their demands for ‘equality before the law’ would not advance the ‘ultimate elevation, not only of the coloured, but of the great masses of the people of the United States’. Decades of lynching and Jim Crow laws followed, practices that Manjapra terms ‘a political tool of war emancipation’.

Manjapra’s explanation of what happened in Haiti also comes within the fold of ‘war emancipation’. The enslaved of Haiti (known as Saint-Domingue to its French colonists) revolted for thirteen years from 1791 to expel their oppressors – the only European slave colony to do so. The Haitian revolution is among the most dramatically operatic histories of the modern world, but Manjapra is particularly interested in its second act: the French-led isolation of an independent, Black-led Haiti through global trade blockades. Embargoes from all the major European and American states crippled the Haitian economy and led to Act Three, more than twenty years later.

In 1825, King Charles X of France offered to concede the independence of Haiti, giving it access to the international trading community and international law, in exchange for Haiti’s agreeing to the French version of emancipation. It was, in Manjapra’s terms, a patently ‘absurd emancipation professing to retroactively free a people who had freed themselves two decades earlier’. Under this arrangement, Haiti had to pay France an indemnité of 150 million francs, around US$37 billion in today’s money. This they set out to do, with around eighty per cent of Haiti’s revenue going towards the debt in some periods. It was finally paid off 120 years later, in 1949.

Britain enacted something similar under its scheme for emancipation, paying £20 million to slave-owners from 1834. The enslaved were required to labour for a further four years as apprentices, netting slave-owners a further £27 million worth of free labour. Manjapra notes that when the debt to slave-owners was finally paid off in 2015, the British Treasury tweeted: ‘Did you know? In 1833, Britain used 20 million, 40 percent of its national budget, to buy freedom for all slaves in the Empire.’ This cheery missive’s flimsy grasp of history might have been more extensively plumbed by Manjapra (all of those enslaved in India remained enslaved, for instance), but within the arc of his argument there can be no doubting its grotesque glibness. A footnote from this section reveals that Manjapra sought comment from the Rothschilds, whose forebears financed the scheme. This is history-cum-journalism.

The notion that compensating slave-owners and gradualist emancipation was a requisite of freedom is something Manjapra challenges by pointing to contemporary critics of such schemes. In miniature biographies, Manjapra places individual experience within wider contexts, explaining what is unique and typical of these lives. He quotes Robert Wedderburn, the son of an enslaved woman and slave-owning man, who lobbied for abolition in London from 1813. He cites Elizabeth Heyrick, a Leicester Quaker abolitionist, whose 1824 book Immediate, not Gradual Abolition called for compensation for the enslaved. He tells the story of Callie House, born into slavery in Tennessee in 1861, who established the National Ex-Slave Mutual Relief Association, which counted three hundred thousand subscribers and lobbied for reparations for the enslaved.

In recent decades, historians have found innovative ways of visually communicating Atlantic slavery. Here again, Manjapra does not disappoint, bestowing on the reader a terrific map showing benefits of emancipation to slave-owners and a centrefold with wonderfully juxtaposed images.

Black Ghost of Empire concludes by arguing for reparations and anniversaries that commemorate freedom. Such undertakings are as much for the present as for the future, Manjapra argues, for they cultivate ‘continued watchfulness and vigilance’ towards acts of oppression. This book, after all, is history for now. It is history that moves from the archive to the reader’s mind. ‘Think of it,’ Manjapra urges us: ‘linger with the voids’.

Comments powered by CComment