- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: History

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Flares and embers

- Article Subtitle: A richly detailed analysis of American exceptionalism

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

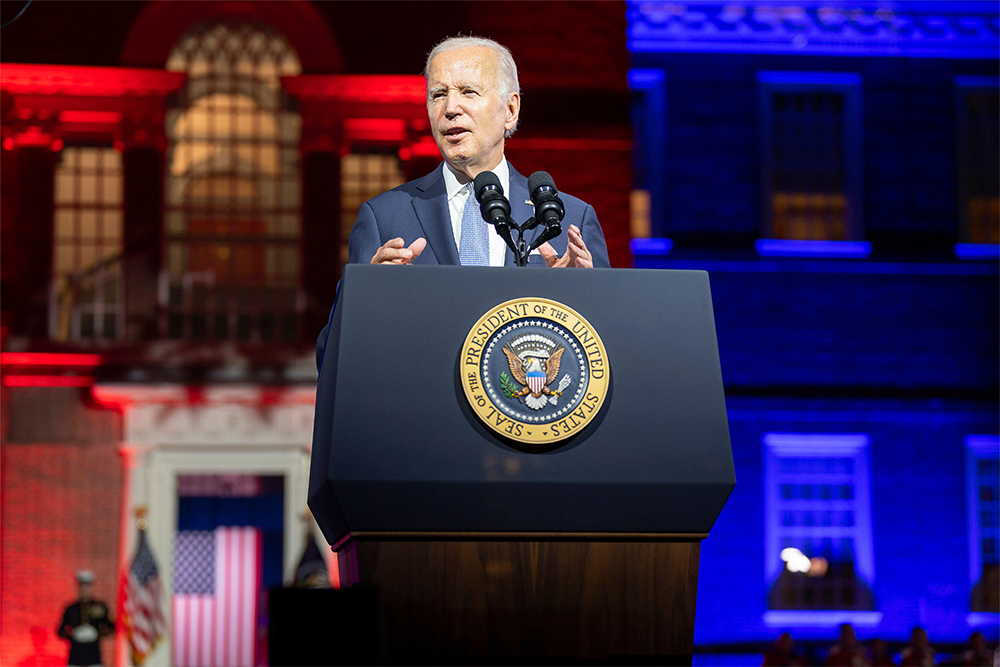

The forty-sixth president of the United States, like most of his predecessors, is an avid student of American history. In August 2022, Joe Biden met for the second time with a group of pre-eminent historians to discuss his presidency and the many threats facing American democracy. A month later, standing in Independence Hall in Philadelphia, he told the American people: ‘I know our history.’ Biden has, from the beginning of his campaign for the presidency, characterised his own period of American history as a ‘battle for the soul of the nation’, riffing off historian Jon Meacham’s book The Soul of America: The battle for our better angels (2018).

- Article Hero Image (920px wide):

- Article Hero Image Caption: US President Joe Biden speaking at Independence Hall in Philadelphia, 2022 (Adam Schultz/White House Photo/Alamy Live News

- Alt Tag (Article Hero Image): US President Joe Biden speaking at Independence Hall in Philadelphia, 2022 (Adam Schultz/White House Photo/Alamy Live News

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Emma Shortis reviews 'American Exceptionalism: A new history of an old idea' by Ian Tyrrell

- Book 1 Title: American Exceptionalism

- Book 1 Subtitle: A new history of an old idea

- Book 1 Biblio: University of Chicago Press, $57.95 hb, 288 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/jWbKae

Those wishing to understand that ‘battle’, and the role of presidents, historians, and Biden’s audience – the American people themselves – in fighting it out, need look no further than Ian Tyrrell’s meticulous and engaging history of American exceptionalism. Tyrrell’s ‘new history of an old idea’ offers students and followers of American history a richly detailed and compelling historical analysis of the changing, contested, and slippery set of ideas that underlie exceptionalism. Tyrrell’s analysis of exceptionalism and its corollaries is absolutely necessary to understanding how it is that a president standing before a people and warning them of the existential threat to their democracy can, in almost the same breath, claim that they live in ‘the greatest nation on the face of the earth’, one that has ‘for more than two centuries … been a beacon to the world.’

As Tyrrell outlines early on in American Exceptionalism, Biden’s invocation of ‘greatness’ is not necessarily synonymous with exceptionalism – in fact, the difference between those two ideas is ‘foundational’. It is this careful parsing of that underlying set of ideas that informs exceptionalism, in all its forms, that is perhaps the greatest strength of the book. Tyrrell offers precise definitions of those ideas, so that a capitalised ‘American Exceptionalism’ is understood as something quite different to lower-case ‘exceptionalism’, which itself has historically contingent and ever-changing relationships with cultural nationalism, Christian republicanism, Anglo-Saxonism, Manifest Destiny, the American Dream, the American Century, and their subsidiary myths. While this definition and historical explanation of terms has every chance of being dry and stale, this is far from the case – Tyrrell’s claim to offer a ‘new history’ is one that he more than lives up to.

American Exceptionalism has a more or less chronological structure, tracing the ever-changing nature of exceptionalism from the beginning of European colonisation to the present day. In each chapter, through tours of the major touch points in American history, Tyrrell traces the influence of events like the Revolution, the movement to abolish slavery, the Civil War, the New Deal, and the Cold War, and how their memories were and are still made, shaped, and changed, as they themselves changed understandings and makings of exceptionalism. Tyrrell identifies the forces that have made, and often strained, exceptionalism over centuries as international, transnational (particularly the transatlantic), domestic, cultural, and religious, and notes the impact of communities and individuals. In so doing, Tyrrell shows how ‘Exceptionalism had morphed into an ideology reflecting and shaping a social and political worldview, and through which public policy was refracted.’

In tracing this change over time, Tyrrell reveals the deep intellectual and cultural origins of Biden’s understanding of the United States as a ‘beacon’ to the rest of the world – an idea that is connected to, but differs in important ways from, Ronald Reagan’s ‘Shining City on a Hill’ in the 1980s, John F. Kennedy’s ‘City upon a Hill’ two decades before that, and John Winthrop’s similar evocation in the seventeenth century. This idea has been made and remade, and interacted in often surprising ways with Americans, their histories, and their environments. That analysis of the complex relationship between individuals, the state, and the environment is one that is particularly exciting. Drawing on the discipline of environmental history, Tyrrell shows, for example, how the violence of westward expansion and the ‘end’ of the frontier, slavery, and Manifest Destiny ‘unraveled’ Christian republicanism, once again changing the nature of American exceptionalism.

In this ‘new history’, Tyrrell is seeking to disrupt otherwise accepted understandings of the history of American exceptionalism to show ‘how settler colonialism and its denial underpinned U.S. exceptionalism’. In engaging with a narrative around ‘settler colonialism’, Tyrrell hopes to broaden a common and self-reinforcing analytical frame that focuses narrowly on the United States itself. This is not a new argument, but it is a critical one. In many ways, Tyrrell is successful, but in others he undermines the case. Early in the book – much of which deals with questions of race directly – the qualifier ‘white’ is added in brackets, so that a descriptor will become, for example, ‘adult (white) males’. This may seem like a minor point, but such a construction seems to bracket questions of race in the development of early American exceptionalism, when in fact they were fundamental. Just as Biden was recently, and rightly, criticised for inviting only (white) historians to discuss threats to American democracy, this bracketing has significant implications tied to the violence of exceptionalism. Tyrrell, perhaps unlike his colleagues who received that invitation to the White House, shows that this violence is deeply rooted in the history of Americans’ ideas about themselves, characterising the Civil War as ‘a moral conflict grounded in a dispute over the nature of American exceptionalism’. That conflict has never been resolved; as a result, ‘the United States faced, and still does face, the flares and embers of an inner civil war’.

Tyrrell’s analysis of what the United States faces today, and of the modern iterations of American exceptionalism, is unique precisely because it rests on such solid foundations of historical analysis. While it is possible to detect, here, a historian’s reluctance to diagnose the present, Tyrrell’s argument that the way that ‘the discourse of American decline has grown at the same time that the affirmation of exceptionalism has intensified and become a matter of political and ideological conformity … is a departure from the past’ is utterly convincing.

Much of what Tyrrell writes about – the changing nature of ideas, and how ideas are made and constantly revised – is, as he argues, ‘impossible to measure precisely’. In American Exceptionalism, Tyrrell does the hard work of the historian, untangling threads and rejecting simplistic diagnoses.

A student of different historians, the president told his constituents in September 2022: ‘Now, America must choose to move forward or to move backwards, to build a future or obsess about the past.’ Ian Tyrrell’s major contribution is to demonstrate how ‘obsessing about the past’ is entirely necessary for understanding the dramatic and historically contingent present of ‘the greatest nation on the face of the earth’.

Comments powered by CComment