- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Essay Collection

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: A scandalous insistence

- Article Subtitle: In pursuit of social change

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, a number of cycling groups in Europe were founded on socialist principles. I had some notion, before reading Jeff Sparrow’s Provocations, of the link between cycling and that era’s feminist politics – the independent, bloomer-clad woman on her bicycle, which Sparrow also sketches – but not of Italy’s Ciclisti Rossi (Red Cyclists) or England’s Clarion Cycling Club. The latter’s anthem celebrated its members’ two-wheeled role in advancing class struggle.

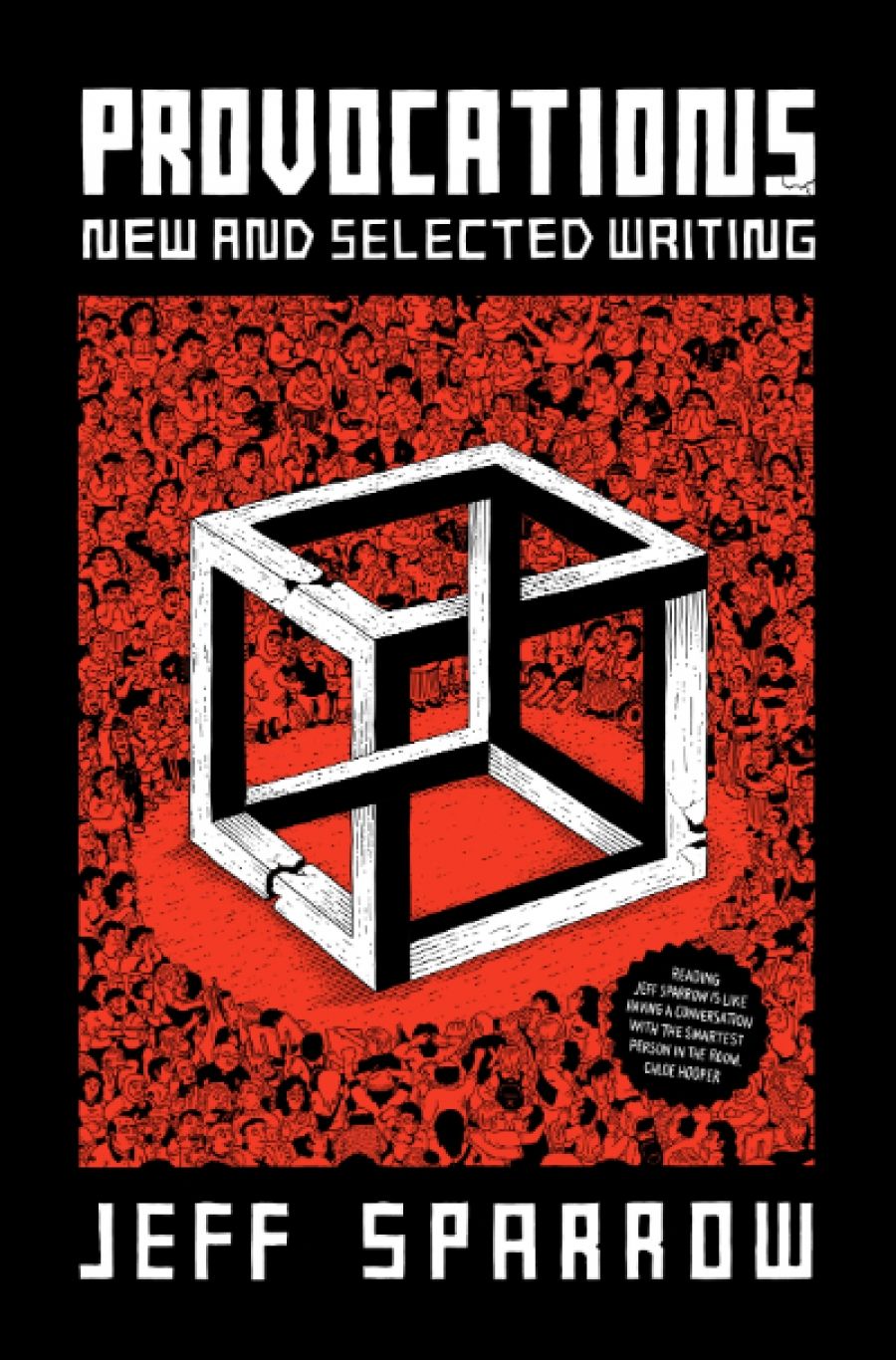

- Book 1 Title: Provocations

- Book 1 Subtitle: New and selected writings

- Book 1 Biblio: NewSouth, $32.99 pb, 399 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/mgMxrq

Jeff Sparrow (photograph via UNSW)

Jeff Sparrow (photograph via UNSW)

Provocations brings together short and shortish essays written by Sparrow over an almost fifteen-year period, on a range of subjects and political questions: the earliest, from 2007, is a sympathetic if ultimately sceptical profile of historical re-enactors, those weekend war enthusiasts, written for Overland. The most recent, which was written for, and closes, the book, examines the contemporary popularity of dachshunds in light of the anti-German prejudice that marred Australian society during World War I. Sparrow’s project as a writer and critic is a serious one, but he also writes within a tradition of left-wing critics and historians, among them Eric Hobsbawm, Ellen Willis, Raymond Williams, and Stuart Hall, who have been willing and able to address substantial political questions through the prism of popular culture and popular phenomena.

The book is thickly studded with quotations and historical examples, and the pieces are concentrated marvels of research. The display of knowledge is rigorous, its intention generous: these are essays aimed at a general readership, many of them having originated as columns in the Guardian. Unlike the output of many newspaper columnists, Sparrow’s writing is not disfigured by either ahistoricism or condescension towards his readers. ‘Genuine radicalism provides hope,’ he writes in the book’s introduction. ‘It provokes through a scandalous insistence that life can be otherwise … that we can make our future better than our past.’ Hence the book’s title, ‘not an endorsement of culture war contrarianism’ so much as a call for readers to think with the author through the complications of history, in pursuit of change.

A crucial part of this intellectual interplay lies in Sparrow’s ability to challenge the assumptions of left-wing readers. In a 2012 essay, ‘Gun Control and Rage Massacres’, for instance, Sparrow provides a nuanced reading of gun ownership in the United States. ‘As soon as you move from abstractions to real history,’ he writes, the cartoonish cliché of the gun-toting right-wing militant is complicated by historical evidence showing that gun control measures were directed, for a long time, against Black people in the United States, who have had most reason to want to arm themselves for protection, and who have faced the most severe crackdowns for carrying weapons.

Sparrow’s essay is by no means an argument in favour of more guns, but he does take care to distinguish between police or government-directed gun control measures, which continue to be strongly resisted in the United States, and a community-led, ‘bottom-up solution to the proliferation of guns’ that does not cede to the far right ‘the mantle of opposition to state power’. The latter is something that the Australian left could agitate for, again in an internationalist spirit.

The passage of time has not invalidated Sparrow’s argument, especially since the far right has continued to present itself, as Trump did, as an insurgent force while holding the levers of state power. But another question concerning time nagged at me while I was reading this book, and it’s a question that applies to any collection of previously published pieces where the original purpose of the writing was reactive, and tied to the news cycle. What is the time, after the fact of their original publication, in which these pieces are best read?

I wonder if the real value of Provocations will be felt by a reader long into the future, when the contemporary events that Sparrow has responded to will have become historical. The book will then constitute a record, both of things that happened in the first two decades of the twenty-first century, particularly in Australia – the specific horrors of our nation’s border policies, the transformation of Anzac Day into a quasi-religious ritual – and of one thoughtful writer’s insistence, in the face of those things, upon the need for a fundamental reorganisation of our society, in line with the socialist principles of those long-ago riders of the Clarion Club.

For the present-day reader, some of these contemporary events are stranded in that disquieting zone between news and history: we have already forgotten the details that Sparrow might only refer to in passing because they were fresh in the mind of his original readership. There is something poignant in this; public memory is very short. If part of Sparrow’s purpose in these pieces is to counteract our forgetting, then that counteraction is also, at the moment, most effective in the pieces where the subject is already historical: the cycling essay, for instance, or the collection’s opening piece, written for the book itself, on indentured Pacific Island labourers in Australia.

‘The past cannot be altered,’ writes Sparrow, in that essay’s conclusion, ‘but it can, perhaps, inspire a different future.’

Comments powered by CComment