- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: The Daily Dan

- Article Subtitle: A timely political biography

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

During his first electoral campaign, Daniel Andrews hung a sign in his office containing a timeless political wisdom from Lyndon Baines Johnson: ‘If you do everything, you will win.’ He has continued taking it literally. Australian politics has, it is agreed, few harder workers than Victoria’s premier: he is in the same class as LBJ, who famously said that he seldom thought about politics more than eighteen hours a day.

- Article Hero Image (920px wide):

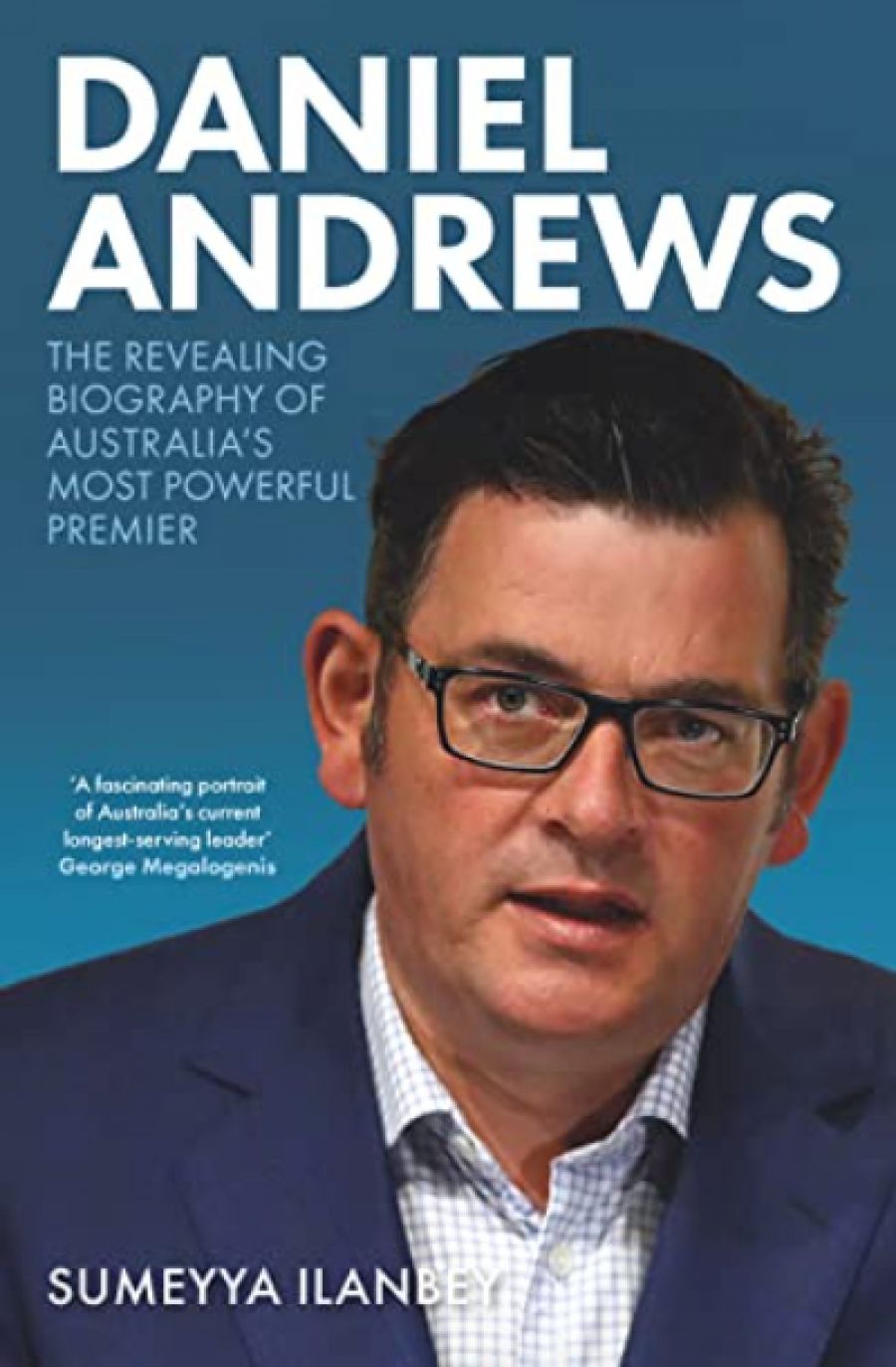

- Article Hero Image Caption: Premier Daniel Andrews (photograph via SOPA Images/Alamy)

- Alt Tag (Article Hero Image): Premier Daniel Andrews (photograph via SOPA Images/Alamy)

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Gideon Haigh reviews 'Daniel Andrews: The revealing biography of Australia’s most powerful premier' by Sumeyya Ilanbey

- Book 1 Title: Daniel Andrews

- Book 1 Subtitle: The revealing biography of Australia’s most powerful premier

- Book 1 Biblio: Allen & Unwin, 312 pp, $26.95 pb

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/3PQbXX

Andrews also does as close to everything in his government as it is possible to do, dismissive of parliamentary process, indifferent to Cabinet government. His huge personal staff, somewhere in the region of one hundred, is said to be larger than the personal staff of the entire Victorian lower house. He has presided over a politicising of the public service that may never be reversed and will legitimise a tit-for-tat response, and his studied insouciance has been absorbed by others. ‘Don’t admit where you got it wrong and make it all about that,’ he counselled South Australia’s premier, Peter Malinauskas. ‘It feels good today, but they will just beat you over the head with it.’

In this sense, Andrews, who will most certainly stampede to a third term at the polls on 26 November, deserves to be regarded as his generation’s most consequential Labor politician, making Daniel Andrews, by The Age’s state political reporter Sumeyya Ilanbey, one of the timelier political biographies.

One of the more fascinating impacts of Covid-19 on journalism was to turn state rounds, which had for decades been stripped of prestige and experience in favour of concentrating dwindling resources in Canberra, into a premium posting. In Melbourne, furthermore, one could go nowhere, do nothing – reporters, like everyone else, were for much of the time stuck at home, confined and curfewed.

Victoria’s state rounds-people suddenly found themselves in proximity to what was guaranteed to be the day’s biggest event: the press conferences that became known, over 120 consecutive days, as the Daily Dan, with Andrews live-streaming his Saint Sebastian act, braving the arrows of Ilanbey and her colleagues.

The grinding monotony of their content notwithstanding, livestreams of the Daily Dan commanded huge audiences and generated maelstroms of social media commentary. Their legend continues to grow. ‘That’s a level of resilience and stamina that I find extraordinary,’ Labor jobs minister Martin Pakula tells Ilanbey. ‘It was a tour de force.’ Well, step aside Volodymyr Zelensky.

Oh purlease! Ilanbey has it just about right when she identifies the Daily Dan as ‘propaganda cloaked as accountability’, quoting an unnamed Labor source as wishing Andrews had spent as much time on the hotel quarantine program as he had on press conferences. And young as she is – twenty-eight – Ilanbey has a pleasing fearlessness.

Among the most bizarre features of the last two years in Victoria has been the herd of independent minds on Twitter dedicated to depicting Andrews’s Covid response as one masterstroke after another – despite the state recording the worst health, social, and economic outcomes of any in Australia – with no deeper reasoning than: ‘You’re alive, aren’t you? Be grateful!’

Journalists who have dared report otherwise – on the opaque secrecy around public health advice, on the self-defeating idée fixe with Covid-zero, on the psychological toll of six lockdowns, on shambles like hotel quarantine and the furloughing of staff at St Basil’s, on the punitive cruelty meted out to residents of the Alfred Street housing commission flats and to the tens of thousands indiscriminately penalised for often trivial lockdown breaches – have had to run a gauntlet of jeering whataboutists and other useful idiots.

Ilanbey, refreshingly, has a crack. Journalists have grown too accustomed to trading access for independence – what Paul Keating called ‘the drip feed’, and what the ABC still sneakily acknowledges in the title of Insiders. She may slip a little too readily into the pugilistic vernacular of the political column: there are too many ‘factional warlords’ and ‘factional brawlers’, too many ‘guns blazing’ across too many ‘firing lines’; the health portfolio is twice described as a ‘poisoned chalice’; Victorians will also be surprised to learn that they have ‘never been resource-rich’, given that their colony was built on gold, and that their state has long been powered by abundant coal and gas.

But Ilanbey has a clear sight both of Andrews, ‘a man who thinks highly of himself and his talents’, and the modus oper-Andrews: ‘When confronted with a crisis, refuse to answer the substantive question, defer to another authority or an investigation, even if you’re legally allowed to comment, and when asked about discrepancies in your answers, shrug your shoulders and say you stand by your comments.’

Such is the protective cordon around Victoria’s premier. Andrews the man is bound to elude Ilanbey. She struggles to get behind the scenes of anything terribly much. To be fair, a live government is as difficult to write of as an athlete still competing. She can impart little of Andrews’s emotional make-up or his family background – what are his tastes and relaxations, what makes him laugh and cry. Developments in his personal life are scattered and superficial (‘On the home front, he would welcome his first child, Noah, just a few months after the election’).

Yet there may not be much to say. It feels, after a while, as though there can be scarcely a non-political bone in Andrews’s body. He has allies rather than friends. He has gestures rather than vision. Even his more laudable achievements as a progressive politician – legislation for the decriminalisation of abortion and assisted dying, support for medicinal cannabis, and adoption rights for same-sex couples – have involved calculatedly minimal expenditures of electoral capital.

Despite his huge majority, Andrews has let less tractable issues go, including, ignominiously, the management of his own party, which he had to cede to the federal ALP, such was its culture of grift and graft. His period as health minister (2007–10) is recalled for the manipulation of figures for hospital waiting times, the subject of a damning report by the auditor-general. His period as gaming minister (2006–7) preluded a royal commission into Crown Casino that was, as Ilanbey observes, ‘a lifeline disguised as a punishment’.

Ilanbey’s most useful insights perhaps concern not Andrews but Victoria, where Labor has a decidedly mixed report card for having been in power for nineteen of the last twenty-three years: the state is per capita Australia’s second-poorest, its economic growth having depended overwhelmingly on population increases which reversed during Covid-19; its health services, vulnerabilities revealed by the pandemic, are gravely overstretched; its schools, overmanaged and under resourced, are the lowest funded in Australia.

On housing affordability and social housing availability, the state ranks poorly. Half the inmates in Victorian prisons are on remand, with Indigenous women the fastest-growing demographic. Family violence statistics remain little changed despite lots of solemn promises. Infrastructure projects cost multiples of their initial estimates, which Andrews has dismissed airily: ‘These things cost what they cost. Anyone that’s done a kitchen reno, for heaven’s sake, knows that.’ He doesn’t hold the kitchen reno, mate.

A half-competent opposition would be having a field day; Victoria’s hapless Liberal Party, of course, resembles an office of particularly dim estate agents. And, ironically, some of the best of Andrews was seen in the role Matthew Guy has now. Ilanbey lays out well how quickly and effectively Andrews picked up and dusted off Labor during its interregnum of 2010 to 2014. His colleagues were not exactly grateful, squabbling petulantly over Cabinet positions while they were allocated as factional spoils.

Maybe this explains a little. Maybe Andrews is the logical outcome of the degeneration of contemporary politics, its reinforcement of an amoral careerism, its effectiveness at filtering out anyone with half a clue about anything. Whatever one may say of Andrews, he is in his way able, focused, and diligent, where his ministers remind you of that sketch in Spitting Image where Margaret Thatcher is in a restaurant with her Cabinet and ordering raw steak from the maître’d. ‘What about the vegetables?’ she is asked. ‘They’ll have the same as me,’ Maggie replies.

Of Andrews, a Labor colleague complains to Ilanbey: ‘He’s always more concerned about looking after his enemies than working with his friends. He holds parliament in contempt. There’s a lot of support internally – you can call that loyalty – but a lot of people who support him don’t really like him.’ This was a depressing comment on the imagined compatibility of the culture of party politics and niceties of the Westminster system. Andrews reminds us, then, of a comment apocryphally attributed to another American president, Harry Truman: that those who wanted a friend in politics should get a dog.

Comments powered by CComment