- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Letter collection

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: The New Jerusalem

- Article Subtitle: Filtering experience through the grid of the finite

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Of the major Anglo-American poets of the previous century, none was more transformed, at least on the surface, by the journey across the Atlantic than Thom Gunn (1929–2004). Travelling in the opposite direction, T.S. Eliot found echoes of his mid-Western emotional repression and discreet anti-Semitism in the England of his era, while W.H. Auden, who carried his world with him, was only mildly affected by his time in America.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Ian Dickson reviews 'The Letters of Thom Gunn' edited by Michael Nott, August Kleinzahler, and Clive Wilmer

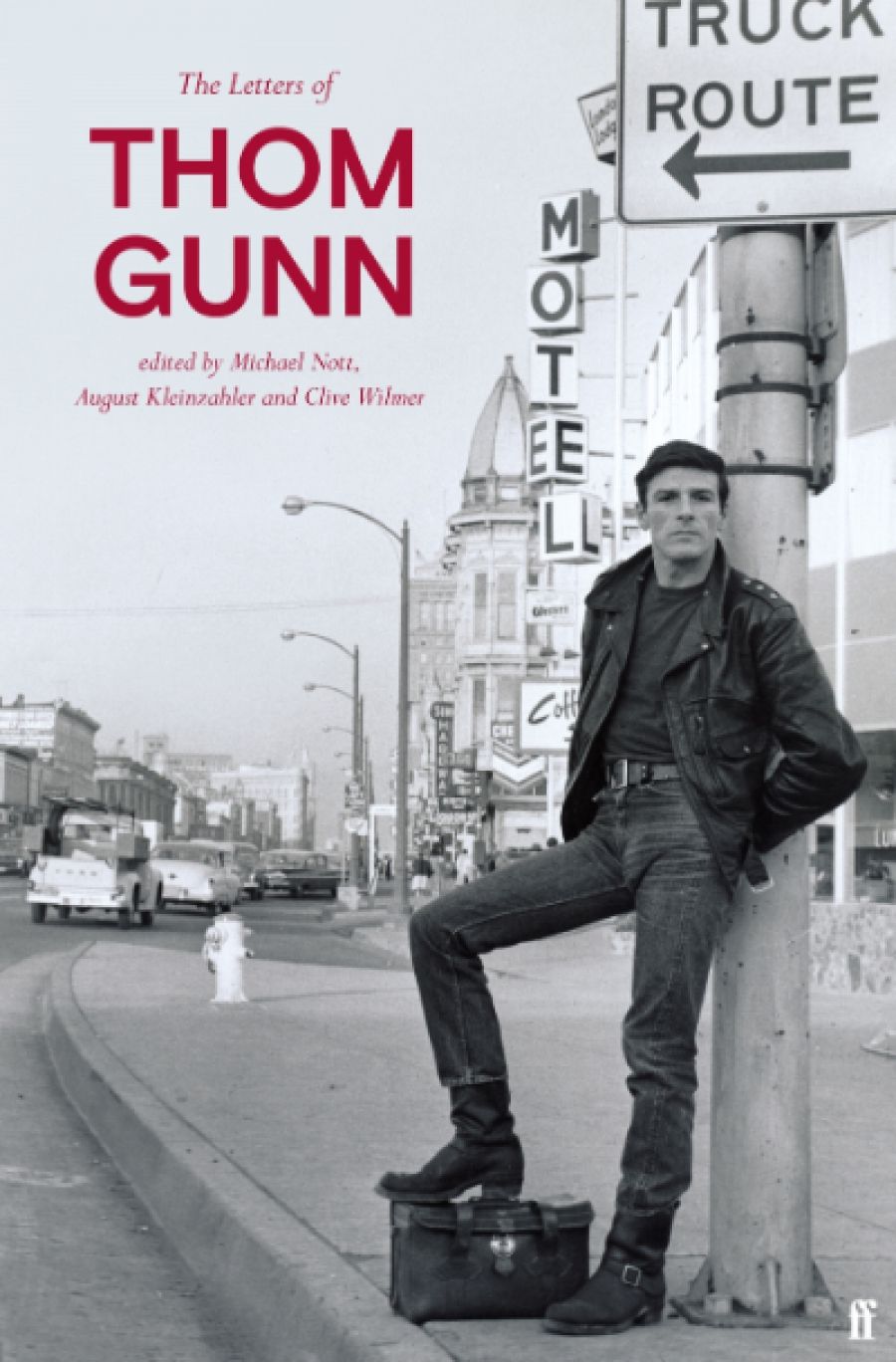

- Book 1 Title: The Letters of Thom Gunn

- Book 1 Biblio: Faber, $79.99 hb, 734 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/oeDxq9

When Gunn left England in 1954, he was a closeted academic who had just published his first collection of poetry, a cautious, emotionally reticent selection called Fighting Terms. By the time of his death from ‘acute polysubstance abuse’ in 2004, he was a gay spokesman openly celebrating the druggy, leather scenes of San Francisco and New York and mourning the friends and lovers who had died in the 1980s and 1990s. His English critics threw up their hands in maidenly horror as his subject matter became more overt and his poetic style relaxed into syllabics and, finally, free verse. But Gunn never entirely abandoned rhyme and metre. Commenting on the fact that many of his drug-related poems are metrical, he claims he was ‘filtering the experiences of the infinite through the grid of the finite’. In Eavan Boland’s words: ‘Few poets in our time have been so deeply nourished by tradition and as lovingly open to change.’ In a late poem, ‘Saturday Night’, Gunn leads us on an evocative tour of a torrid night in a 1970s bathhouse in Dantesque terza rima. Virgil outfitted by Tom of Finland.

Gunn always claimed his childhood – spent first in Kent, then in Hampstead – was a happy one, though his father, a successful journalist and editor, and his mother divorced when he was ten. This idyll came to an abrupt end five years later when Thom and his brother, Ander, pushed open a barricaded door to find their mother’s dead body. Gunn adored her. In an unpublished poem he wrote: ‘Yet / of course, we were lovers. / Who could equal you, dazzling / contradictory woman? If it is true / to say that you made me queer, it is equally true / to say you made me a poet.’ But it was only in his final collection that he was able to write openly about her suicide. He abhorred confessional poetry. In an early letter he states: ‘I don’t want to write of my emotions according to their intensity, but to the competence with which I can treat them.’ He makes his great poem about his mother’s death, ‘The Gas Poker’, work by ‘withdraw[ing] the first person and writ[ing] about it in the third person’.

After a boring period in National Service and a few revelatory years at Cambridge, he followed his then lover and subsequent life partner, Mike Kitay, to the United States, eventually settling in the Haight in San Francisco, where he lived until his death.

Surprisingly, there is yet to be a comprehensive biography of Gunn. But this collection of his letters, edited by Michael Nott, August Kleinzahler, and Clive Wilmer, with a perceptive introduction by Nott and a comprehensive chronology which acts as the shilling life, is a fascinating and revealing complement to his poetry.

Because in his work he refused to wallow in his emotions, Gunn has been inaccurately named a ‘cold’ poet. But there is nothing cold about the man who wrote these letters. The editors seem to have winnowed the recipients down to a fairly limited number, but the tone and the topics vary widely. There are the letters to the family: dutiful ones to the father to whom Gunn was never close; carefully bowdlerised ones to his aunts; and warm ones to Ander.

As he is creating, Gunn reaches out to trusted friends for critical feedback. He makes enlightening comments about what he is trying to achieve in specific poems and proffers drafts which are intriguingly different from finished works. In a letter to his friend Tony Tanner, he subjects the poem ‘Innocence’ to a line-by-line dissection asking for ‘your further advice, because there are real problems with it I can’t work out by myself’.

There is also plenty of literary discussion and gossip. Writing to Christopher Isherwood, he tells him: ‘I would like to write poetry with the same sort of power as your prose.’ At a first meeting, Auden, whose early work he admires, is a disappointment. ‘I could hardly believe this was the Wild One of the thirties … a flabby dilettante, gracious living, complacent and trite.’ Allen Ginsberg, on the other hand, whose work he at first finds uncongenial, is a pleasant surprise. ‘I met Ginsberg for the first time and was hugely impressed: I’d always thought he might be a bit hysterical, like some of his poetry, but he is sensible and kind and takes charge and looks after people in a way I admire.’ He describes Elizabeth Bishop as ‘a person of a certain superficial formality – in a very nice way – beneath which is really a great openness to experience’.

In a letter to Ander, he reacts to the dismissive reviews with which the British critics greeted his collection The Passages of Joy (1982). ‘You may have noticed that my latest books have ruffled the calm of the London literary establishment, who range from snide (Observer) to really vicious (our old friend Ian Hamilton, of course, who seems bent on extending a career founded almost entirely on malice!, in the Times Lit. Sup) … if I am being punished by them for not sharing in their preconceptions about poetry and sexuality, then so much the better – I’m in less danger than being contaminated by their praise.’

For gay men in the Western world who made it to the big-city ghettos, the 1960s and 1970s were a time of ebullient improvisation and experiment. As Gunn remarks: ‘We were making things up as we went along.’ Gunn threw himself into the scene, but this caused tensions with Kitay, who was by nature more monogamous. For a while they split, and the letters Gunn writes as they try to discover a modus vivendi that would work for them are the emotional heart of the book. Responding to Kitay’s accusation of coldness, Gunn makes a personal declaration that could be as relevant to his work as to his personality. ‘You always credit me with lack of feeling because I often don’t show feeling … but I admire the understatement of feeling more than anything … Like in Handel … and Racine … the feelings in them are contained within a clean and strong framework.’

Gunn’s appetite for drugs was as rampant as his appetite for sex. In a long letter to Tanner, he attempts to describe a particularly powerful trip. While admitting that ‘People who go on about their trips are very boring’, he suggests that, ‘One thing it does … is to present as possible still the choices one had thought were settled long ago.’ A more successful attempt to describe the experience is his poem ‘A Fair in the Woods’, one of the poems that most riled the British critics. It is an almost too apt poem in which this devotee of Edmund Spenser and pharmaceuticals attends a costumed pageant, Renaissance Fair, in the San Raphael Woods while tripping on LSD.

As the AIDS epidemic takes hold of his community, the tone of the letters changes. In the poem ‘Elegy’, he writes: ‘They keep leaving me / and they don’t / tell me they don’t / warn me that this is / the last time I’ll be seeing them.’

As he aged, Gunn became more of an elder statesman for both the gay and the literary communities. His letter to the academic and poet Gregory Woods commenting on Woods’s reading of his work is an exemplar of tactful criticism (‘I find you innocently misleading – you are never malicious, just over-ingenious’).

Elder statesman he may have become, but his Rabelaisian side never disappeared. Recalling the 1970s, when it seemed as though the gay community was inventing what he called a New Jerusalem, he writes: ‘There are many varieties of New Jerusalem, / Political, pharmaceutical – I’ve visited most of them. / But of all the embodiments ever built, I’d only return to one, / For the sexual New Jerusalem was by far the greatest fun.’

Comments powered by CComment