- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Tribute

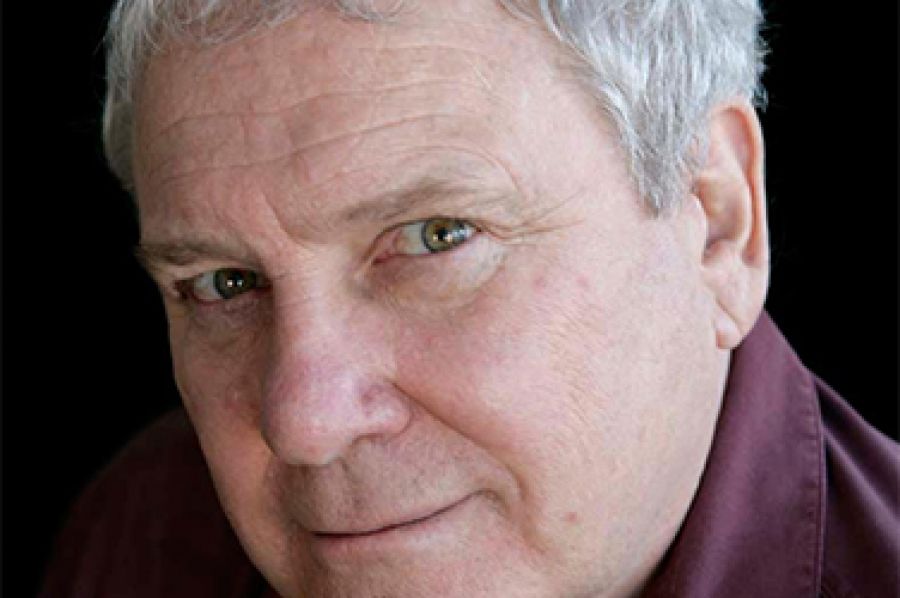

- Custom Article Title: A tribute to Frank Moorhouse

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: A tribute to Frank Moorhouse

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Frank Moorhouse, one of Australia’s most prolific and loved authors, essayists, and public intellectuals, died aged eighty-three on 26 June. Moorhouse left a legacy of eighteen fiction and non-fiction books, a series of screenplays, and countless essays. He was also a tireless activist on a range of fronts, including opposing censorship and promoting copyright law reform.

- Article Hero Image (920px wide):

- Article Hero Image Caption: Frank Moorhouse (photograph by Kylie Melinda Smith/Penguin)

- Alt Tag (Article Hero Image): Frank Moorhouse (photograph by Kylie Melinda Smith/Penguin)

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): 'A tribute to Frank Moorhouse' by Catharine Lumby

Moorhouse left Nowra at the age of seventeen to become a cadet on the Daily Telegraph. He had a complicated relationship to his origins. He wrote often about the South Coast and loosely based a character on his father in his third book, The Electrical Experience (1974), who also appears in his League of Nations novels, Grand Days (1993) and Dark Palace (2000). When I asked him in an interview about how much growing up in Nowra influenced him, he said, somewhat tongue in cheek: ‘I’m always writing about Nowra. You could say everything I’ve ever written is about Nowra.’

In 1959, Moorhouse married his childhood sweetheart Wendy Halloway (now Wendy James), who was also an aspiring writer. The marriage did not last long, but James and Moorhouse remained in touch intermittently until his death. When Moorhouse published his semi-fictional memoir Martini in 2005, James took exception to the way she was portrayed in a thinly veiled character based on letters she wrote to Moorhouse as a teenager, and wrote a lengthy piece in The Australian in 2007.

Moorhouse left journalism at the age of thirty to become a full-time writer, an audacious career move at the time. From his earliest days as a writer, Moorhouse infused his work with accounts of political and social issues that defined the milieu and broader society he narrates. His writing is also frequently and transparently entangled with his life. Not that he directly translates people and events – no writer does. Moorhouse once told me that characters in his fiction were parts of a ‘discarded self’. The same characters recur in his early work: Milton and Anderson being two key examples. Both are semi-fictionalised, or refracted, references to his friends of the time: Milton to the scholar and writer Michael Wilding; Anderson to his long-time friend, the scholar and literary critic Don Anderson.

Moorhouse is known for his use of what he dubbed the ‘discontinuous narrative’, a narrative style that stitches together his short stories into a larger narrative relying on the device of recurring characters and themes – threads that Moorhouse pulls together to weave a more complex and novel-like story.

In his first book Futility and Other Animals, published in 1969, Moorhouse set about renovating the short story and bringing it into the present day. His style is already apparent: knowing self-deprecation, irony, an uneasy yet complicit relationship with the intellectual life, and a searching approach to received ideas about gender, sexuality, and human relationships.

What is remarkable in hindsight is the characteristic frankness with which Moorhouse narrates and names the uncertainty and the dissonances that attended the social change affecting sexual identities and gender roles at the time of writing. The Americans, Baby was published in 1972, at a time when homosexual acts between men were still criminalised in all Australian states and when the gay liberation movement was in its infancy. Moorhouse has never been pegged as a ‘gay’ writer, but he was one of our earliest fiction writers to openly tackle the subject and to do so through characters who were sometimes bisexual.

To understand the way the women’s liberation and the gay liberation movements unfolded in Sydney in the 1970s, and the issues that Moorhouse was implicitly grappling with in his early work, it is critical to see the fingerprints that the Libertarian movement, known as the Sydney Push, left on Sydney intellectual and political life. Moorhouse often described himself to me in interviews as a left-wing anarchist, by which he meant that he was suspicious of hard-line ideology on either the left or the right and rejected a polemical or doctrinaire approach to debate. On the issue of free speech, about which he and journalist and academic Wendy Bacon led anti-censorship battles in the 1970s, he was fascinated by how many rules we need to live civilised lives. His instinct was to question why laws or rules were put in place and whom they protected.

His major work, the League of Nations trilogy, was prompted by his fascination with the grand scheme the League embodied: to design rules for civilised living for the global community. He spent years in the archives funded by the newly established Australia Council Creative Fellowship, also known as the Keating Fellowship.

In the first book of the trilogy, Grand Days, Edith Campbell Berry arrives in Geneva to work at the newly created League of Nations amid an atmosphere of heady idealism. Dark Palace, for which he won the 2001 Miles Franklin Literary Award, chronicles the fall of the League as Hitler comes to power. The third, Cold Light (2011), is set in Canberra, where Edith returns after World War II, and focuses on the building of the capital and the anxiety at the heart of Australian national identity.

Moorhouse, at times, found himself the subject of unwelcome controversy in the literary world. Grand Days was bizarrely dismissed from contention by the Miles Franklin judges on the grounds that it was ‘insufficiently Australian’, despite being a book that interrogates the meaning of borders and features a young woman from the south coast of New South Wales. As Moorhouse noted in a speech to a literary lunch at the time, the book examines: ‘the crossing of borders and the meaning of borders, national and other, and identity.’

Moorhouse also wrote a number of screenplays, including for the movie The Coca-Cola Kid (1985), directed by Dušan Makavejev and produced by David Roe. Moorhouse’s oeuvre is remarkable not only for his productivity but equally for his ability to write in the voice of female characters. Writer and commentator Annabel Crabb, who launched Cold Light, founded the unofficial Edith Campbell Berry fan club. She says of Edith: ‘There’s a joy in finding a [female] character who is complicated, who’s appealing, is clever, but fallible … She feels like a gift to me.’

Moorhouse worked closely with publisher Jane Palfreyman and later with Meredith Curnow at Random House. Palfreyman says that working with him on Grand Days, Dark Palace, and Martini: A memoir were life and career highlights for her and that Moorhouse was an ‘astonishing talent, a true original and one of our finest writers’.

Moorhouse had many intense and loving relationships throughout his life and a wide circle of friends, too numerous to name here. He loved the rituals of eating out, drinking, and engaging in excellent conversation. He was a bon vivant and a very witty raconteur.

He is survived by his brothers Owen and Arthur. His memorial was held at the State Library of NSW on 13 July. Among the speakers were literary critic and scholar Don Anderson and the author Tom Kenneally, both friends and admirers of his work.

Comments powered by CComment