- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Literary Studies

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: The <em>Ulysses</em> century

- Article Subtitle: Reflecting on James Joyce’s work a hundred years on

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

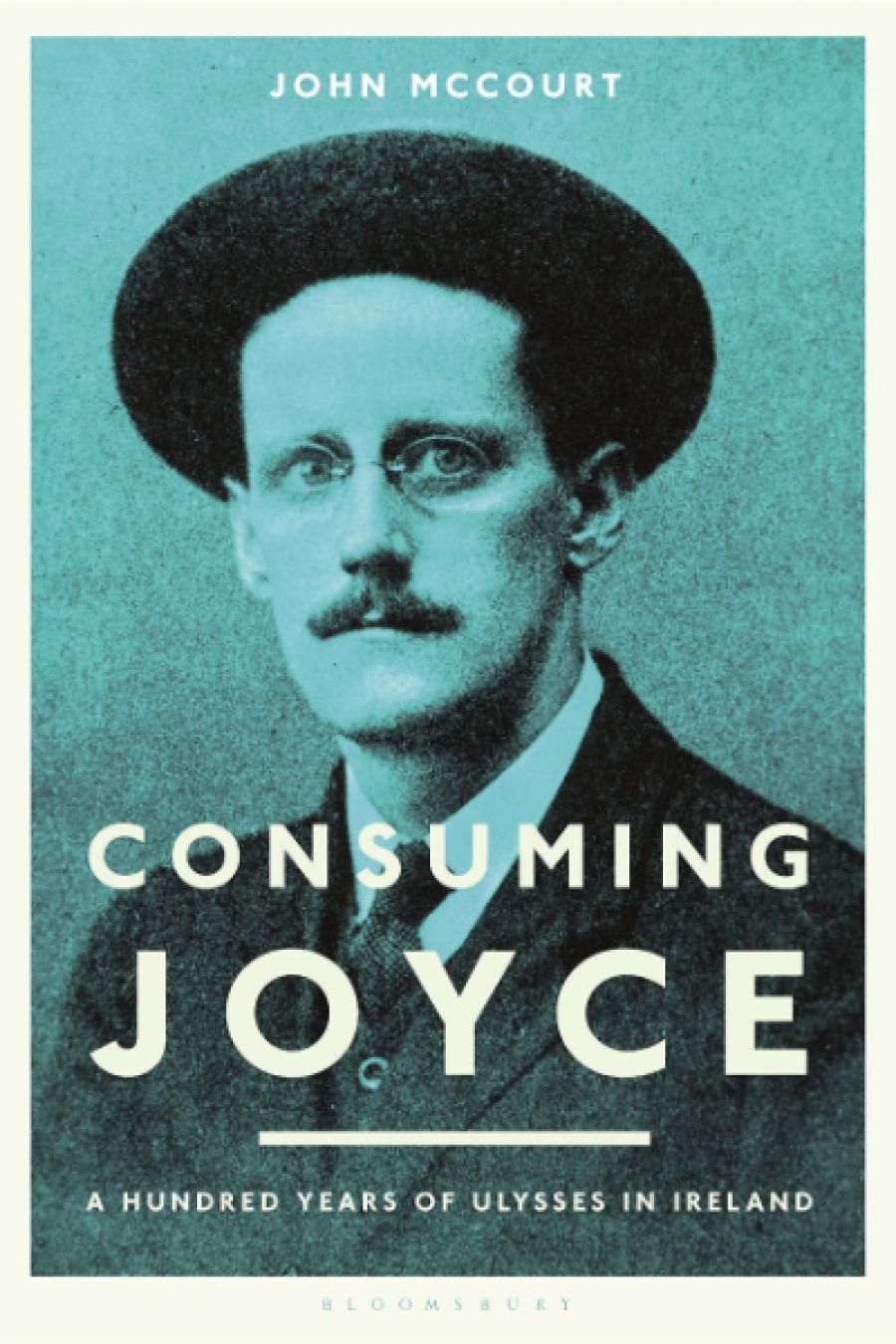

James Joyce’s Ulysses was published 100 years ago by American Sylvia Beach, who ran a Parisian bookstore called Shakespeare and Company. The early history of the work was marked by controversy and censorship. The centenary is being marked by numerous publications in celebration of the work by writers, academic Joyceans, and even the odd Irish ambassador. John McCourt’s Consuming Joyce: 100 years of Ulysses in Ireland traces the reception of Ulysses in Ireland. As much a book about Ireland as it is about Ulysses, it follows the critical, institutional, and popular reception/consumption of the work through the different phases of Irish history.

- Article Hero Image (920px wide):

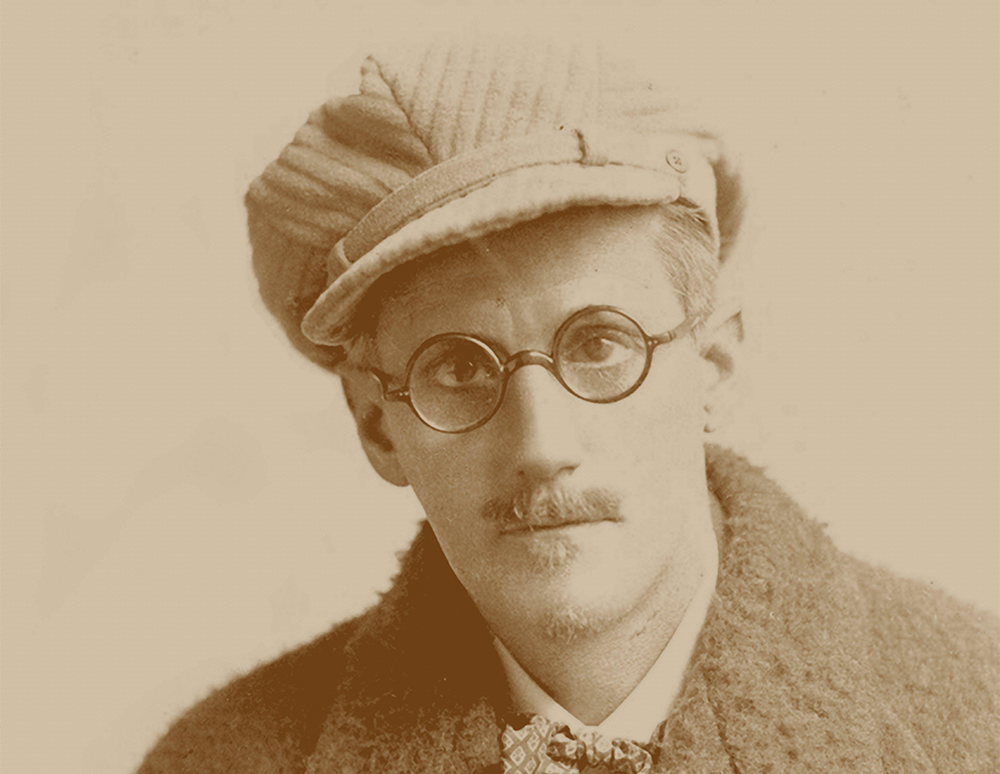

- Article Hero Image Caption: Irish novelist James Joyce (photograph via Alamy)

- Alt Tag (Article Hero Image): Irish novelist James Joyce (photograph via Alamy)

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Gary Pearce reviews 'Consuming Joyce: 100 Years of Ulysses in Ireland' by John McCourt and 'One Hundred Years of James Joyce’s Ulysses' edited by Colm Tóibín

- Book 1 Title: Consuming Joyce

- Book 1 Subtitle: 100 Years of Ulysses in Ireland

- Book 1 Biblio: Bloomsbury Academic, $130 hb, 304 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/Aoedoj

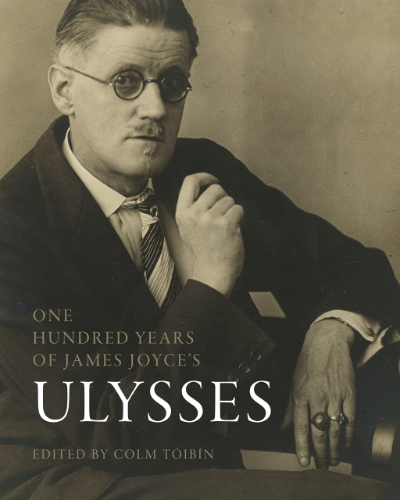

- Book 2 Title: One Hundred Years of James Joyce’s Ulysses

- Book 2 Biblio: Pennsylvania State University Press, US$45 hb, 184 pp

- Book 2 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 2 Cover (800 x 1200):

- Book 2 Cover Path (no longer required): images/ABR_Digitising_2022/July_2022/META/One Hundred Years of James Joyce's Ulysses.jpg

- Book 2 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/15BX5R

When Joyce moved from Ireland into European exile in 1904, he burnt his bridges by employing an ‘unsparing realism’ in his early writing targeted at Ireland’s paralysis and isolation. Ezra Pound’s depiction of Joyce as shedding his Irish background to become an international writer would shape many subsequent interpretations. More recently, there has been recognition of the determining influence that Ireland had on Joyce’s work. McCourt examines the background to this shift by delving into the Irish archive and tracing a line of response to Ulysses that emphasised the Irish Joyce. He recognises that this was a minority response to a work that, more typically, was regarded with hostility or indifference. Ulysses was written during a period of national and political ferment and was published in 1922, the same year as the founding of the Irish Free State. Those turbulent times meant there was little mood for indulging critical voices. The hostile response was focused on the book’s treatment of a Catholic Church that was aligning itself with the new Irish state. Critics such as Mary and Padraic Colum, however, understood the importance of Irishness and Catholicism to Joyce’s own world view. McCourt situates him among an emergent generation of Catholics destined to take leadership positions in the new Irish nation.

McCourt’s prodigious research ranges across reviews and other published responses; government attitudes; book consumption; tourism activity; and the response of writers, academics, and intellectuals. The emphasis on cultural and economic self-sufficiency under Éamon de Valera’s government in the 1930s allowed little place for exiles like Joyce. McCourt is particularly interesting when he documents the response to Ulysses by dissident nationalists who saw in Joyce an alternative vision beyond the conformity and parochialism of the new state. This was a period of growing censorship. While Ulysses wasn’t banned in Ireland, it was regarded as contraband. Meanwhile, Joyce’s growing international reputation placed him on the cover of Time magazine. Writers’ responses tended to be more complicated; early admirers such as Seán Ó Faoláin and Frank O’Connor became alienated when the excerpts of Finnegans Wake were published in different literary periodicals. Nevertheless, young Joyceans like Brian Coffey and Brian O’Nolan (Flann O’Brien) were inclined to question censorship and the nationalist status quo.

The other important strain that McCourt examines is the tension between the Irish response to Ulysses and the emerging US academic scholarship in the 1950s. The first Bloomsday (16 June) in 1954, celebrating the setting of Ulysses, was led by a distinguished gathering of writers that included Brian O’Nolan, Patrick Kavanagh, and others. McCourt notes that this event was largely ignored. The first collection of Irish writing on Joyce in the periodical Envoy adopted a grudging tone and was critical of American academic attention to Joyce. The American literary critic Richard Ellmann also arrived in 1954 and let it be known that he was writing a biography of Joyce (it would be published five years later). McCourt notes a hostility to American Joyceans at this time. New Criticism held sway in the United States, treating works as self-contained and universal rather than being explicable by external circumstances of authorship and historical context. The problem was that the Irish academic response to Joyce was underdeveloped and dominated by memoir and reminiscence.

McCourt notes how Joyce came to symbolise a more liberal Ireland from the 1960s onwards. A key moment in the wider acceptance of Joyce was the formation of the Joyce Tower Society in the 1960s to support the museum at the Martello Tower in Sandycove that forms the backdrop to the opening scenes in Ulysses. This was followed by early documentaries, a film, and international symposia. These developments would sometimes attract disapproval and controversy. The mainstreaming of Joyce and Ulysses through commercialisation and tourism would continue to draw criticism. However, by the centenary of Joyce’s birth in 1982, Ireland had made its peace with him. After some initial foot dragging, the Dublin City Council swung its support behind the celebration. By the time of the Celtic Tiger economy in the 1990s, Ireland was post-nationalist, pro-European, pro-capital, and Joyce was ‘official culture’. After decades of government resistance to concerning itself with the material culture commemorating Joyce, an astonishing €16 million was spent on Joyce manuscripts and material for different national collections.

McCourt also records a contrary movement on the part of postcolonial critics who placed Ireland within a Third World history and Ulysses within a canon of resistance literature. This seems a key moment in questioning the idea of a high modernist Joyce divorced from local concerns. McCourt is resistant to this ‘greening of Joyce’, pointing to his own ‘attempt to give voice to a more nuanced and rooted European or Triestine Joyce’. McCourt’s agreement with criticism that the overly political approach of those like Seamus Deane defeats literary appreciation in advance leaves its own assumptions unexamined, as does the attempt to reconcile these positions through ‘semi-colonial’ approaches. Nevertheless, his last chapter documents new voices and approaches that signal the arrival of Irish scholarship within international Joyce studies.

One Hundred Years of James Joyce’s Ulysses focuses its attention more explicitly on the material heritage of Ulysses. It is generously illustrated by manuscripts, portraits, and photographs from different US collections. Tóibín’s introduction situates the whole within the historical and social background to Ulysses. He discusses the role of song as a kind of yearning and aspiration, the transformations in Ulysses’s setting of Dublin, and suggests that the book acted as a blueprint for a society in the making. The collection opens with a group of essays by distinguished Irish academics, including McCourt, that focus on the circumstances within which the writing took place, that is, in the cities with which Joyce is most closely associated: Dublin, Trieste, Zurich, and Paris. There follow essays that focus further on Joyce’s rewriting and revisioning of Ulysses, its manuscripts, the library collections that house them, its publication, and censorship.

In one of the more interesting essays, Anne Fogarty argues that Ulysses is not just about Dublin but is a ‘staging and embodying’ of its chaotic materiality that manages to change what is possible for the novel form. McCourt’s essay argues that Joyce’s move to Trieste, with its European and modernist affiliations, allowed him to progress from the depiction of paralysis contained in his early work to a more expansive and composite perspective in Ulysses. Both Ronan Crowley’s essay on Zurich and Catherine Flynn’s on Paris trace the further widening of interpersonal and intertextual reference in these cities, vital to the writing of Ulysses. Flynn points out that some of Joyce’s most stylistically innovative chapters were written in Paris, where he drew on writers like Édouard Dujardin, Gustave Flaubert, and Alfred Jarry.

These essays are followed by Maria DiBattista’s discussion of how Ulysses evolved across its different published versions as Joyce continued to edit the text obsessively, even as he received proofs from the printers. She characterises this obsessiveness as the ‘art of surfeit’: naturalistic detail was piled on, with a new novel form emerging from a combination of fact-checking and mythography. An essay by trial lawyer Joseph M. Hassett follows the court case brought by the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice that led to the effective banning of Ulysses in 1921. He also outlines the overturning of the ban in a 1934 court case that transformed the application of censorship to works of art. The complications of Joyce’s writing process are illustrated by another essay on the so-called Rosenbach manuscript, the surviving complete manuscript of Ulysses named after Philadelphia dealer A.S.W. Rosenbach. Close examination of this manuscript reveals it to be simultaneously an advanced draft, a collateral text, fair copy, and final manuscript. The last essays are on one of the main US Joyce collections at the University of Buffalo, along with the Sean and Mary Kelly Collection that forms the core of the Joyce collection at the Morgan.

Inevitably, there is an element of celebration and even public relations in a book like One Hundred Years of James Joyce’s Ulysses. But it confirms McCourt’s observation in Consuming Joyce that Irish academics have found their place within international Joyce studies. The discussion of the cities and geographies associated with the writing of Ulysses, along with the fascinating and impressively illustrated history of the book itself, make it a useful and absorbing document to mark this moment. In some ways, the narrative outlined in McCourt’s new work is also a celebratory one, a story of increasing openness and sophistication in the Irish context. There may have been a lost opportunity to engage more extensively with how the politics of modernist cultures might disturb this narrative. Nevertheless, as studies of the history of the production and consumption of Ulysses, both works prove indispensable for gaining perspective on the centenary.

Comments powered by CComment