- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Loneliness in the lazaret

- Article Subtitle: Fiction that is a shade too careful

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

A child of nine is taken to Sydney for the first time to visit her mother, a patient at the Coast Hospital lazaret. Upon arrival, she learns that she, like her mother, has leprosy. Her fate is fixed from that day; she will live the remainder of her life in the lazaret. She takes the new name of ‘Alice’ to hide her former self, and the world closes in upon her. There will be no more school, no playing with her younger brothers and sisters, no friends of her own age, no prospect of romance, no hope of freedom.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Penny Russell reviews 'The Coast' by Eleanor Limprecht

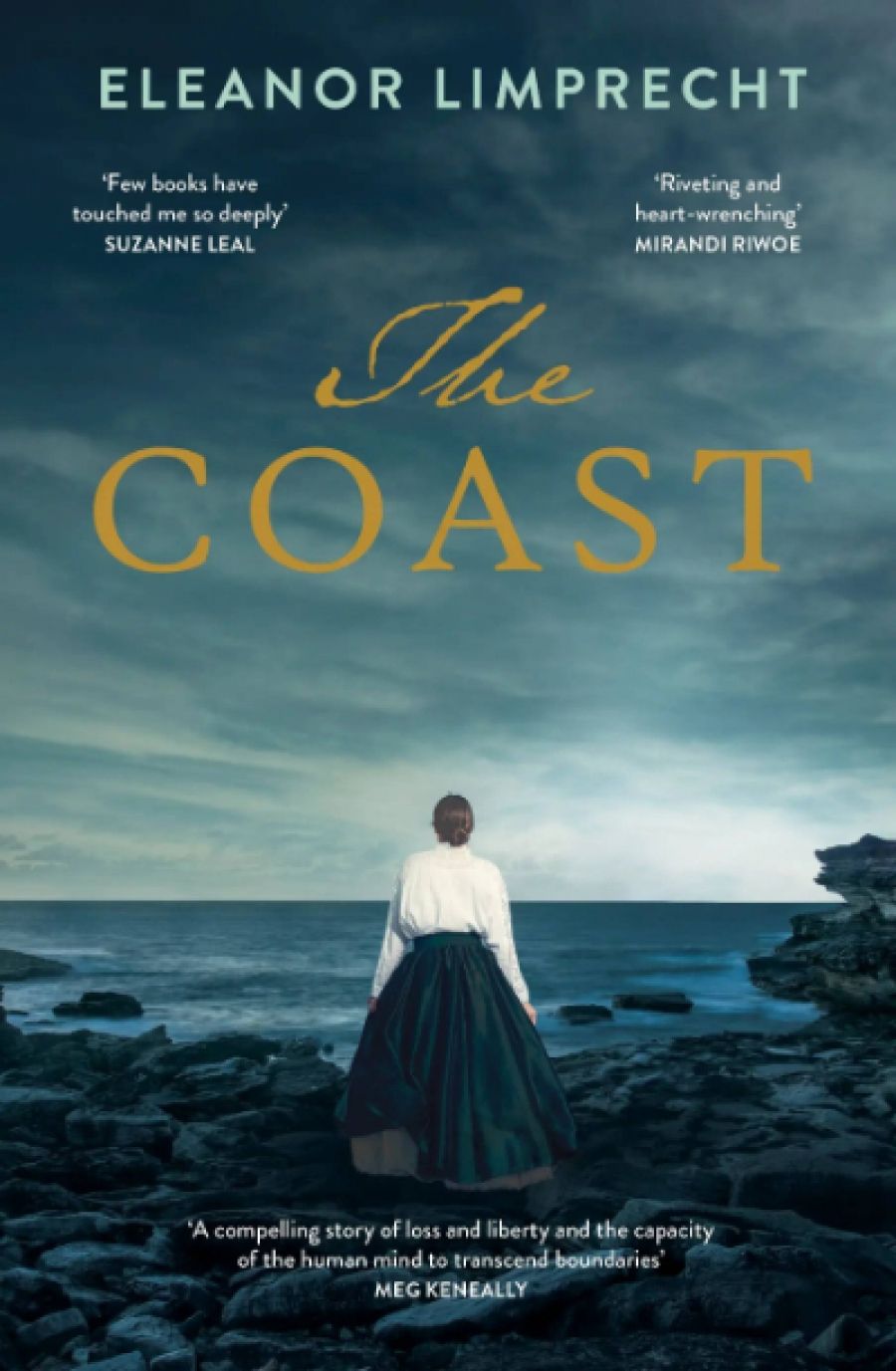

- Book 1 Title: The Coast

- Book 1 Biblio: Allen & Unwin, $32.99 pb, 334 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/0JogQM

Alice’s mother finds refuge from loneliness in sensual pleasure – the company of men, the consolations of grog. Mother and daughter confront the emotional complexities of their relationship under the benevolent gaze of the doctor, Will Stenger, who fights for his patients while battling his own demons of isolation and loss. The arrival at the hospital of Jack, a Yuwaalaraay man known in the lazaret as Guy, briefly transforms Alice’s world.

Eleanor Limprecht (photograph via author's website)

Eleanor Limprecht (photograph via author's website)

With its plot weaving across several decades, from the 1890s to the 1920s, The Coast is a meticulously researched historical novel. Eleanor Limprecht sketches striking images of crowded Sydney streets, the exigencies of rural poverty, the discomforts and indignities of transport, the menacing presence of prejudice and fear. She is informative on medical and surgical treatments of leprosy, conditions in the Coast Hospital, the arrangement of the lazarets, the entertainments and living conditions of the lifelong inmates. Through Jack’s storyline, she brings in contrasting conditions in other leprosaria, such as Queensland’s Peel Island, describing in shocking detail the racially discriminatory treatment of Aboriginal patients.

It is impossible not to sympathise with the dreams, fears, and frustrations of the four main characters, caught as they are in strangling webs of indifferent bureaucracy. At the same time, I remained oddly detached from their suffering. Perhaps the very plethora of historical detail forestalls an emotional response. It is just a shade too careful, making us aware of an observing authorial presence that hovers above the action and outside the minds of the characters, noticing and duly reporting on the material and social peculiarities of the world they inhabit. Those characters themselves are curiously ineffectual, often appearing more as victims than products, let alone agents, of their historical world. The drama of the plot is not generated by tension between individuals but rather unfolds inexorably from the miserable conditions of the past in which they find themselves, with all its prejudices, hypocrisies, and fears.

It is a past in which they do not quite seem to belong. Against her beautifully crafted historical background, Limprecht sets four main characters whose embodied experience is credibly of their time, but whose views and values are sometimes jarringly anachronistic. It is hard, for example, to think where and how a doctor trained around 1900 could have acquired the attitudes to race, gender, class, or sexuality that Will Stenger holds. His views on leprosy, contagion, and the policy of isolation have certainly been borrowed from a real doctor from the period, E.H. Molesworth. But when Molesworth waxed eloquent on the cruelty of isolating leprosy patients from the world, his sympathies were strictly qualified. Isolation was unnecessary for those of European race, he insisted, for they had greater resistance to the disease than ‘native’ and ‘coloured’ races. To be confined for life in the company of those more susceptible races was, in his view, a particularly cruel punishment for white Australians.

Limprecht selectively borrows Molesworth’s words, massaging them to fit a character who will not offend her readers: Stenger unites his progressive medical opinions with enlightened and respectful views on race. I wished that Limprecht had peopled her historical world with characters whose sensibility was more recognisably a product of it, who shared its moral values and failings, but who nevertheless engaged our interest, even our reluctant sympathies. Instead, she invites our sympathy for characters who, though born in the twenty-first century, seem to have been tossed by bitter circumstance and a malicious author onto the stormy waves of a world that is not their own.

As the narrative shifts from one point of view to another, and back and forth through time, sympathy is demanded for each of the major characters in turn. We do not linger long with Alice’s horror at being thrust without warning into lifelong confinement, but move swiftly on to her mother’s own story of betrayal and disappointment. By the time we return to Alice, some chapters later, she is already partly resigned to her lot. There is tragedy and real feeling in the account of Jack’s removal from his family at the age of five; but some of his later experiences seem compressed, hurried, and thus muted in impact. Time sweeps over the characters while our emotions are demanded elsewhere.

The multiple perspectives allow Limprecht to present a broad tapestry of historical experience, and a rich portrait of lives caught and held in fleeting, fragile connection. Greater complexity comes, however, at the cost of diffusing emotional intensity. The trade-off may indeed be intentional. If we stayed always in Alice’s head, locked in her diminishing world of doomed hopes and only gradually, with her, coming to understand the separate burdens carried by the other main characters, this would be a story of almost unbearable poignancy. I wondered at times whether Limprecht was shielding herself as much as her readers from an excess of pain. Together we dip a toe into a sea of anguish, and hastily retreat.

Comments powered by CComment