- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: The face of the deep

- Article Subtitle: A pilgrimage to the border of oblivion

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

On the surface, Scott McCulloch’s début novel, Basin, takes place in a brutal and degenerated landscape; the edge of a former empire in a state of violent flux. Rebels, separatists, terrorists, paramilitary groups, and the remnants of imperial forces clash over borders and interzones in the wake of the ‘Collapse’, an undefined geopolitical and ecological disaster. Print and broadcast media warn of inter-ethnic conflict and Rebel advances. Bazaars, brothels, and a chain of Poseidon Hotels all operate amid industrial waste and military checkpoints, servicing the region’s fishermen, soldiers, smugglers, and drifters. There is a multiplicity of language and religion (Abrahamic denominations mingle with archaic, pagan beliefs). Alcohol consumption and illicit drug use are rife. The climate is oppressively humid.

- Article Hero Image (920px wide):

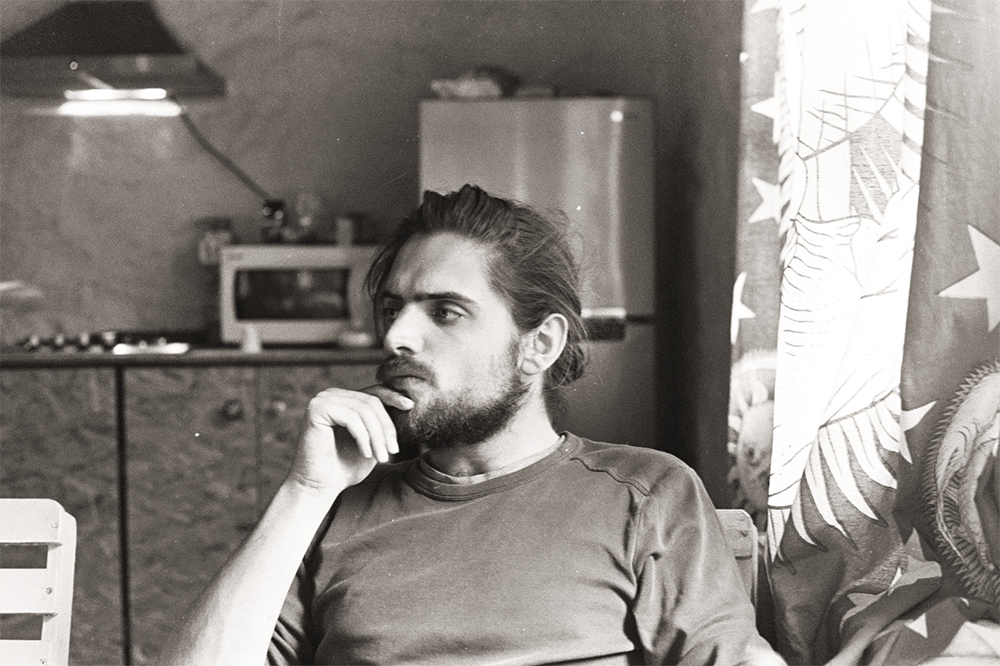

- Article Hero Image Caption: Scott McCulloch (photograph supplied)

- Alt Tag (Article Hero Image): Scott McCulloch (photograph supplied)

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Morgan Nunan reviews 'Basin: A novel' by Scott McCulloch

- Book 1 Title: Basin

- Book 1 Subtitle: A novel

- Book 1 Biblio: Black Inc., $24.99 pb, 186 pp

Enter Figure, McCulloch’s mysterious anti-hero and narrator (named only in the blurb and in the title of the first act), a perpetual exile and nomad; a drug-fuelled ‘tramp’ and public masturbator. For Figure, the war remains ‘illusory’. He is indifferent and dissociated; uncertain of even basic details of the sociocultural context. Early on, he can’t identify a military flag ubiquitous enough to be printed on stickers and towels. Later, he is unsure if the war extends to the Other Isle (he learns fairly quickly that it does). Even after the conflict erupts and surges, forcing him to flee and ramble through a ‘criss-cross’ of seas and rivers, cedar forests and wild steppes (‘[as] a ghost who’s wandered into the odyssey of a lunatic’), Figure maintains a stubborn estrangement.

Part of this is due to his ongoing recovery from a suicide attempt (at the beginning of the book, poisoned and almost drowned, Figure is pulled from the water by a ‘wayward seer’: the deranged paramilitary soldier Aslan). His chronic substance abuse also renders him an inherently unreliable and hallucinatory narrator. There are traces, too, of the sentiment in Theo Angelopoulos’s film Ulysses’ Gaze (1995) (a similarly elliptical road narrative through the war-torn Balkans), when a journalist paradoxically exclaims: ‘What are you looking for? Signs of war? You won’t find any. The war’s so close that it might as well be far away.’ As Basin progresses, a deep, primal ‘amnesia’ shrouds the purgatorial landscape.

McCulloch employs a three-act structure for his protagonist’s wandering journey. Figure drinks with fishermen and shepherds, partakes in fleeting sexual liaisons, witnesses violence and displacement, and benefits from a surprising amount of hospitality. As he covers three broadly distinct regions (by foot, boat, truck, car, and tractor), he oscillates between existential confusion and a yearning for a vague catharsis, with tantalising yet elusive hints at his forgotten past.

The topography of the novel is loosely based on the north-east coastline of the Black Sea and its immediate interior, the southern edge of the Pontic–Caspian steppe (McCulloch has been based between Ukraine and the Caucasus since 2014). While some readers might be tempted to search for references to the region’s recent (and continuing) tumult (the Sukhumi massacre is one likely influence for the major event in the first act), McCulloch undermines parallels to the modern world with the use of fictional or alternative place names and other geographical and historical abstractions (there are eucalypts and cities from antiquity; surrealistic flights). It is a text irreducible to political or historical allegory.

Like Xenophon’s march between the poles of the Aegean and Black Seas, each of the novel’s acts establishes a pattern of anabasis and katabasis; a movement away, then an inevitable return to water. This use of water as the guiding motif is important in the context of a largely plotless narrative, where encounters with minor characters can have shades of the scripted sequences of adventure video games; where the war and its reverberations often act as a McGuffin designed only to propel Figure’s passage from one village to the next. McCulloch’s bold faith in imagery as the connective tissue of the narrative proves to be a great strength.

In obsessively paratactic and incantatory prose, Basin inundates the reader with potent, mesmeric imagery. Echoes of history, mythology, theology, and avant-garde literature and cinema combine in a dogged portrayal of the abject, grotesque, and taboo; collapsing boundaries between past and present, external and internal realities; between bodily and earthly, human and animal. The corporeal writing of Pierre Guyotat and the post-apocalyptic pilgrimage in Konstantin Lopushansky’s film, A Visitor to a Museum (1989), are important precursors that haunt these images.

From the outset (the book begins at chapter ‘0’), McCulloch initiates a dialogue with the primordial abyss, the ‘nudity of Creation’. The swirling mosaic of mythemes on fertility, origins, pilgrimage, flood, and the underworld continues the book’s emphasis on the fluidity of space. The region’s borders and power dynamics arbitrarily shift (fishermen and smugglers haul stock ‘for when the Guard changes again, for when they once again wake up in another new country’). Figure’s Dionysian-like rebirth sees his bodily excretions (his sweat, blood, bile, sperm, and shedding, psoriatic skin) merge and ‘blend’ with the landscape. The first-person, present-tense narration incorporates a ghostly ventriloquism, a disembodied voice which asks early in the book: ‘How many people are we at once?’ The result is a compelling exploration of the nature of creation: the formation of geographical and geopolitical borders; the birth (or rebirth) of the self and its psychological sites; the composition of a work of art.

Basin is a searching, cerebral journey that foregrounds the corporeal in a polyphonic, multilayered text. With a compulsive regard for myth and metaphysics, the novel successfully emerges from the primeval waters of oblivion.

Comments powered by CComment