- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Nowhere places

- Article Subtitle: Welcome contributions to queer fiction

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

At first glance, neither Marlo nor My Heart Is a Little Wild Thing seemed particularly appealing. Both focus on queer men pining for love in a homophobic world. Both appeared to recycle what Jay Carmichael (Marlo’s author) calls ‘the tradition of tragedy in queer literature’. Digging deeper, we find that the novels offer nuanced and even uplifting perspectives on gay male experience over the decades. There are moments of adversity, but it’s the resilience and emotional strength of the protagonists – their ability to find pleasure in even dire situations – that make both books so compelling.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Jay Daniel Thompson reviews 'Marlo' by Jay Carmichael and 'My Heart Is a Little Wild Thing' by Nigel Featherstone

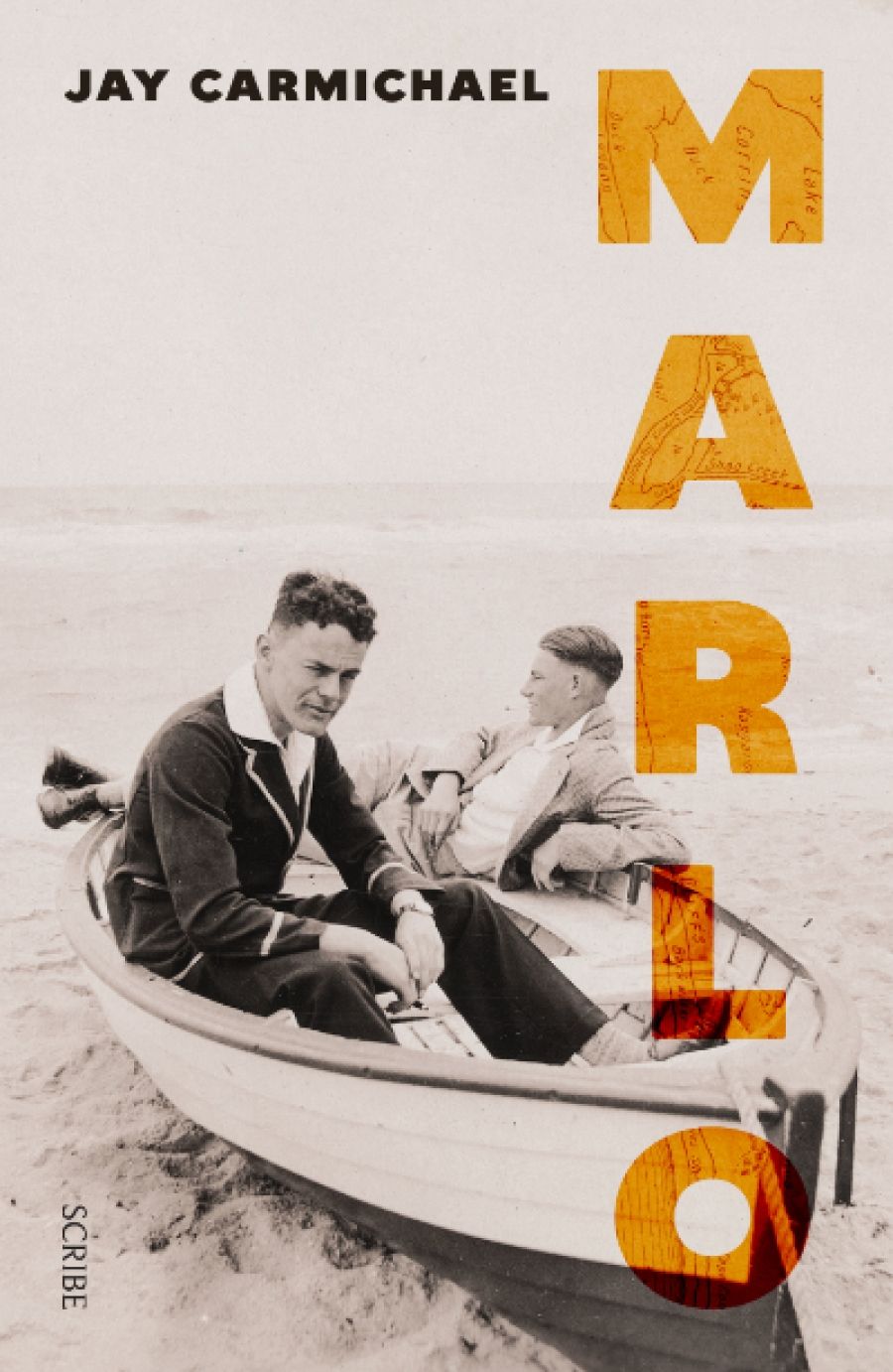

- Book 1 Title: Marlo

- Book 1 Biblio: Scribe, $24.99 pb, 150 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/yRAzGv

- Book 2 Title: My Heart Is a Little Wild Thing

- Book 2 Biblio: Ultimo Press, $32.99 pb, 282 pp

- Book 2 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 2 Cover (800 x 1200):

- Book 2 Cover Path (no longer required): images/ABR_Digitising_2022/July_2022/META/My Heart is a Little Wild Thing.jpg

- Book 2 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/YgPOWm

By day, Christopher toils in a blokey mechanic’s garage. By night he seeks relief from a world ‘not intended for me’ by cruising the Botanic Gardens. This nocturnal wonderland offers a sexual and emotional release, even if that release is tinged with the constant threat of violence. One evening, Christopher meets Morgan, a charming Indigenous man. The pair fall in love and embark on a relationship that unfolds outside – but also in front of – the gaze of a society in which heterosexuality and whiteness are everywhere valorised.

Marlo is bookended with snapshots of archival research. The novel opens with an excerpt from the Crimes Act 1949, which cautioned that any male found to commit an ‘act of gross indecency with another male person shall be guilty of a misdemeanour’ punishable by incarceration. The text concludes with a summary of the societal and legal sanctions that gay men faced during the twentieth century.

These snapshots are useful inasmuch as they contextualise the events described throughout. Carmichael brings to life 1950s Australia with unnerving clarity. The language (including ‘bird’, a crude colloquialism for women) is straight out of the postwar era. The dizzy, drunken excitement of the ‘six o’clock swill’ and the starchy formality of social gatherings are palpable.

Most impressively, Carmichael suggests the inability or reluctance of individuals to see stigmatised ways of being, even as these play out in public spaces. Heterosexual couples stroll obliviously past cafés where gender- and sexually diverse patrons mingle. Male couples share bedrooms and lives, while their straight brethren do not (or will not) ask questions. As Christopher’s sister remarks: ‘Most people trust what they see is true. They don’t stop long enough to see what lies beneath.’ Of course, they choose not to see what is in front of them.

Christopher and Morgan’s relationship is sketched with a touching tenderness, playing out as it does in shadows and sunshine, on trains, and in suburban homes. This is a relationship marked as taboo on two counts (interracial and homosexual); it’s also one that both men mostly refuse to be ashamed of. The reader is mercifully spared the ceaseless despair that is stock in trade for the ‘tragic gay’ genre (see Brokeback Mountain, to which Marlo is likened on the back cover).

My Heart Is a Little Wild Thing unfolds in New South Wales just prior to the Covid-19 pandemic. The book opens in dramatic fashion, with Patrick, the protagonist, declaring: ‘The day after I tried to kill my mother, I tossed some clothes … into my backpack, and left at dawn.’

The reader follows Patrick as he ventures to a childhood holiday home in the country, a ‘nowhere place’ where a simple and carefree existence seems achievable. While there, he falls in love with handsome and enigmatic musician Lewis and gradually embraces the homosexual desire long resisted. Patrick confesses with disarming frankness: ‘I’ve never really come out.’

In what follows, Patrick balances his desire for love and sexual pleasure with his caring responsibilities. His mother, Meredith, has emerged unscathed from the opening attack, though her health rapidly deteriorates through Alzheimer’s disease. Patrick’s love for Meredith is laced with anger and also an uncertainty about who she really is. Strolling around her house, he wonders: ‘What did I really know about the woman who lived here?’

My Heart Is a Little Wild Thing is a coming-out novel, albeit one with a significant difference. Most coming-out narratives focus on youthful protagonists, whereas Patrick is in his early fifties. His queerness is not so much a sudden revelation as a force that has bubbled silently in the background, occasionally acknowledged but seldom acted on. Further, Patrick’s loved ones are aware of his sexuality long before he discloses this to them. The opacity of the line between the seen and unseen is one characteristic that Nigel Featherstone’s novel shares with Marlo. Patrick’s description of homosexuality as a secret society might seem more suitable to 1950s Melbourne than contemporary Sydney, a gay mecca for decades. Yet this comparison, while melodramatic, is understandable given his long sexual silence.

Patrick’s voyage of sexual discovery is nicely paralleled with his quest to learn more about his increasingly frail mother. Neither mission is straightforward; Featherstone avoids easy answers and simplistic psychologising. Patrick encounters anti-gay sentiments, including from Meredith, but these in themselves do not explain his long-standing unwillingness or inability to ‘come out’. He mentions that his mother ‘did things to me’ as a young child, but this is not used to ‘explain’ the protagonist’s queerness or to demonise Meredith. That old, misogynist ‘blame the mother’ trope is refreshingly absent.

The book’s strongest moments depict Patrick’s frequent visits to a nudist beach. This is a space where he can momentarily escape from pressing commitments and engage in sexual encounters with other men. These moments hum with tender eroticism.

Featherstone mostly writes with clarity, though some passages are mired in cliché and earnestness. Patrick embarks on his ‘secret path of desire’ and discovers that ‘[t]here is no greater power than love’. ‘What a dreadful state of affairs is love,’ we are told. Sex scenes are punctuated by dialogue that includes ‘I want you’ and ‘you’re divine’. Such passages are unintentionally amusing; others are cringeworthy. They detract from the novel’s sophistication and freshness.

Marlo and My Heart Is a Little Wild Thing are welcome contributions to the field of Australian queer fiction. Both could so easily have devolved into maudlin misery-fests, but their authors’ eye for the complexities of sexuality and everyday life ensures that neither text meets this fate.

Comments powered by CComment