- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Brooms and cupboards

- Article Subtitle: A familial portrait of the Melbourne art world

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

In 1961, Gwen Harwood submitted a sonnet to the Bulletin under the name of Walter Lehmann. Her poem, ‘Abelard to Eloisa’, held a shocking acrostic secret that many people considered very bad art. Nobody discovered the secret until after it was published. But despite her transgression, as Wikipedia puts it, ‘she found much greater acceptance’ – to the point that she is today considered one of Australia’s greatest poets.

- Article Hero Image (920px wide):

- Article Hero Image Caption: Edwina Preston (photograph supplied)

- Alt Tag (Article Hero Image): Edwina Preston (photograph supplied)

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Jane Sullivan reviews 'Bad Art Mother' by Edwina Preston

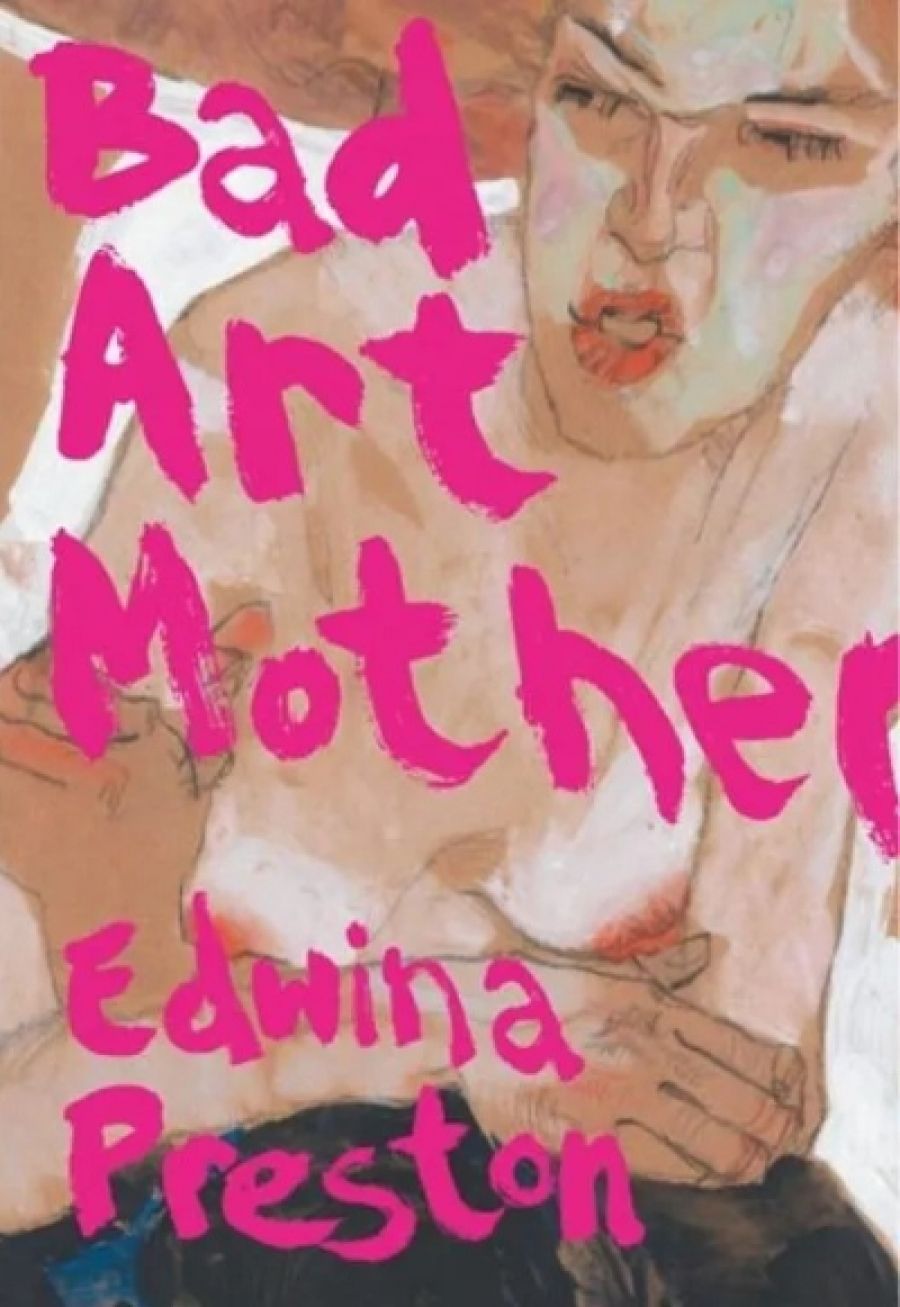

- Book 1 Title: Bad Art Mother

- Book 1 Biblio: Wakefield, $32.95 pb, 324 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/rnrVXd

No such luck for Edwina Preston’s fictional poet, Veda Gray. On the first page of this ferociously funny novel, Preston borrows Harwood’s secret and ascribes it to Veda at the launch of her first book of poetry. When the secret is disclosed, it kills the book – and ultimately, we suspect, it kills Veda. ‘It was 1970,’ says her son Owen, the narrator. ‘Germaine Greer was yet to publish The Female Eunuch. Mother wasn’t a respectable woman.’

Veda confronts the same question that faced Harwood – how to be a poet, a wife, and a mother – but with a different result. Everything works against her ambition. Her husband, Jo, is perennially absent, running a restaurant and feeding the poor. The cultural gatekeepers, all men, see no value in her work and its small, domestic subjects – as Veda describes them, ‘too many brooms and cupboards and pieces from jewellery boxes’. At last, one gatekeeper agrees to publish a book of her poems, but it is constantly delayed and censored by its editors. She fights hard to give herself space and time to create, but unfortunately she’s an expert at self-sabotage, internalising criticism that undermines her confidence. She comes to believe that she has no natural affinity for anything and might have been better off living in a time when women did not learn to read.

Any creative person, particularly any creative woman, will recognise these battles between the outer and inner world. The complacent chauvinism of the postwar era has shaped our culture, and it’s far from dead.

Inevitably, volatile Veda spirals out of control, taking refuge in alcohol and cigarettes and a brittle insouciance that sometimes explodes in bouts of self-destructive fury. In this sense she’s a Bad Mother. Not that she would dream of hurting Owen, though he is often neglected.

He is, however, blessed with two substitute mothers who fill the gaps that Veda leaves wide open. Mrs Parish, a wealthy, childless woman with her own longings, takes the boy under her wing and becomes an adult friend; while his ‘almost-aunt’ Ornella, a grumpy, unmagical Mary Poppins without a creative bone in her body, puts in all the practical care a growing boy needs. It’s no coincidence that Owen is telling his story to Ornella.

Just as there are three mothers to Owen in this story, there are also three women pursuing their own dreams of creativity. Apart from Veda, there is Rosa, a migrant worker in Jo’s restaurant who paints her beloved Dolomites on the walls. Meanwhile, Mrs Parish is quietly snipping away at her ikebana flower arrangements. All are in the shadow of Mr Parish, a celebrated and influential poet who can make or break an artistic career. He is so deeply mired in misogynistic views of women and art that he can’t even recognise his own prejudices.

As the author of a biography of Howard Arkley, Preston already knows a thing or two about art and artists. Here she proves adept at weaving together the tales of her characters against a backdrop of Melbourne in the 1960s, a time when old money and old certainties were challenged by an influx of European migrants and a subversive spirit of entrepreneurial and arty bohemianism. This was typified by the real-life Mora family, with their winning combination of restaurant, art gallery, and outrageous artist in the person of Mirka Mora.

The Moras don’t make it into the novel, but Preston observes this backdrop with a wide-ranging and accurate eye, and a bit of assiduous name-dropping: ‘Max bloody Harris’s bookshop’ or Mrs Parish’s ‘Hal Ludlow’ dress (I’m assuming that ‘Hal’ instead of ‘Hall’ is a typo). But Preston never romanticises the era: Mr Parish and men like him have their deadening hands on artistic hopes.

We feel most sympathy for Veda through Preston’s device of including letters to her sister Tilde, where she can be honest about her feelings – sometimes wistful, sometimes desperate. The dreams of girls are enormous air balloons, she writes – ripe for the pricking.

But the triumph of this engaging novel is the voice of Owen, the boy narrator. He is irresistibly appealing in his earnest bafflement, trying to understand these strange grown-ups, willing to believe the best of everyone, becoming a vegetarian so he can direct his anger and sense of injustice towards the people who kill animals.

Veda is the biggest puzzle because of her moods: ignoring him, shooing him away, then gathering him up and kissing him (‘“poor darling O-yo, Mummy’s such a bad old Mummy” … How could I know what to be, with a mother like that?’). His innocent observation makes for an original, poignant, and often hilarious take on the dilemmas of creative women and the roles that the patriarchy expects them to perform. He is a generous narrator. Even horrid Mr Parish is converted through Owen’s eyes into a figure of pathos. And he’s spot-on in his conclusions about what art does to these people. Art made Mrs Parish ‘calm and strong … Art made Mother sad, Mr Parish silly, and Rosa overexcited.’

We also meet Owen as an adult, keeper of the flame of his mother’s work: after her death, she is finally venerated as a pioneering feminist poet. His partner is the publisher of Veda’s collected works, not a poet but more than a little like Veda herself. I found myself fervently hoping for their happiness.

Comments powered by CComment