- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: From France to Shark Bay

- Article Subtitle: The voyage of Rose and Louis de Freycinet

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

The great age of sail – of European exploration and colonisation – is typically depicted as trenchantly masculine, with the only ‘women’ being unpredictable ships and the sea itself. Women have traditionally been considered bad luck, distracting, or not tough enough for life at sea. Nonetheless, historical research is increasingly revealing that many women played active roles at sea, as commanders, companions, and crew – from the gundecks of Trafalgar, to the topmasts of the American merchant navy, to the French voyages of discovery to the Indo-Pacific and Australia.

- Article Hero Image (920px wide):

- Article Hero Image Caption: Rose and Louis de Freycinet in Dili (Portuguese Timor) in 1818, painted by Charles Duplomb (photograph via State Library of New South Wales Q980/F, Wikimedia Commons)

- Alt Tag (Article Hero Image): Rose and Louis de Freycinet in Dili (Portuguese Timor) in 1818, painted by Charles Duplomb (photograph via State Library of New South Wales Q980/F, Wikimedia Commons)

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Danielle Clode reviews 'Rose: The extraordinary voyage of Rose de Freycinet, the stowaway who sailed around the world for love' by Suzanne Falkiner

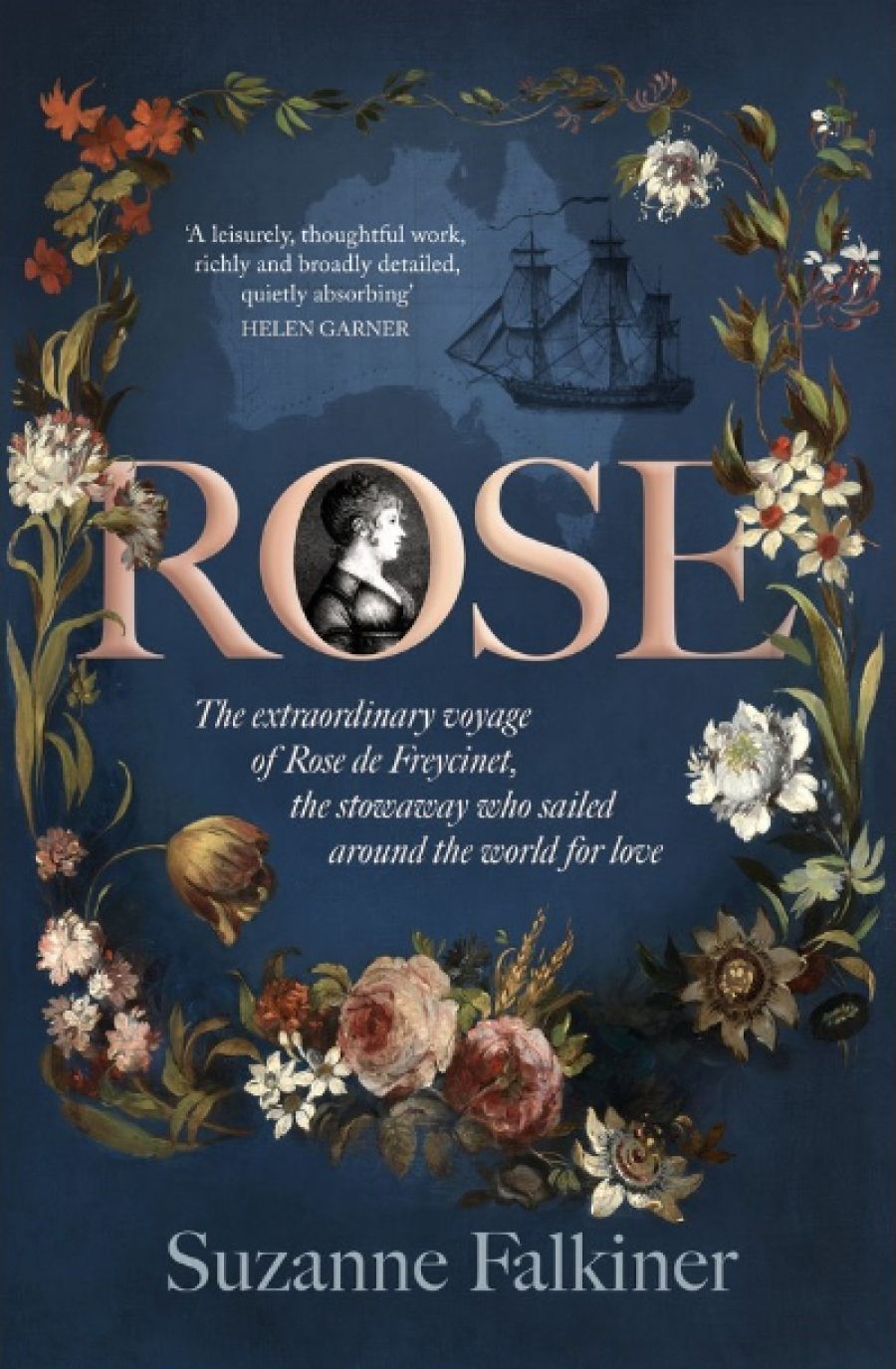

- Book 1 Title: Rose

- Book 1 Subtitle: The extraordinary voyage of Rose de Freycinet, the stowaway who sailed around the world for love

- Book 1 Biblio: ABC Books, $34.99 pb, 404 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/7mq4JV

Rose de Freycinet (1794–1832), the titular subject of Suzanne Falkiner’s latest book, differed from her predecessors in several ways. In 1817, she too disguised herself as a man in order to board the Uranie on its planned circumnavigation of the world. Once onboard, however, Rose soon resumed female dress and sailed in a privileged position as wife of the captain, Louis de Freycinet. She was also the only woman from these French journeys to have left her own written account of her travels in the form of a journal for a friend and letters to her mother.

Rose’s voyage took her from France to South America and Africa, before reaching the shores of Shark Bay in Western Australia, where she enjoyed dining on fresh oysters from the rocks. From here she sailed north through Indonesia up to the Mariana Islands and across to the Hawaiian Islands before finally reaching Port Jackson and the first ‘town with houses built in the European style’ that Rose had seen in eighteen months (and where they were promptly robbed of their silver and linens). The return journey realised Rose’s worst fears: shipwrecked at the Falkland Islands, before they were rescued and taken to Montevideo and returned to France.

On their return Louis faced court martial, not for illegally taking his wife on board, but for the loss of his ship. Absolved on the latter charge, Louis also had his earlier sin mitigated by the king’s judgement that it was an offence unlikely to be copied by many wives.

Despite the title and the cover design, this book is not really a romantic story of ‘the extraordinary voyage of Rose de Freycinet, the stowaway who sailed around the world for love’, but rather an account of the entire expedition, populated by a rich ensemble of remarkable characters. Louis de Freycinet, long regarded as one of the more staid and boring captains, emerges as a complex and earnest character beset by the anxieties and burdens of command. Various members of the de Freycinet and Pinon families crowd the wings of the stage like a Greek chorus proffering sage advice and warnings, and voicing disapproval. Colourful cameos greet the travellers at different ports, some kind and generous, others inhospitable or slightly mad. Some members of the expedition will reappear in future lead roles, such as Louis Isidore Duperrey and Jules Dumont d’Urville, both of whom later commanded their own voyages. Other less well known and perhaps under-appreciated figures are able to come to the fore. Joseph Paul Gaimard and Jean René Constant Quoy, ship’s surgeons and exceptional naturalists, occupy centre stage. Also prominent are the words of Jacques Arago – artist, writer, and adventurer – whose dramatic accounts of travels by ship and balloon would inspire the young Jules Verne. And in the background hovers the ghost of Baudin, the commander of Louis de Freycinet’s formative first scientific expedition, to whom Falkiner unexpectedly devotes the first few chapters.

As the substantial scholarship around Baudin’s controversial voyage attests, the impressive archival resources created by these French expeditions frequently leads to divergent perspectives and interpretations of events. This wealth of material is both the greatest asset and challenge to understanding these voyages. Untangling these interpersonal complexities requires a nuanced and skilful close reading of the divergent narratives, as exemplified by Jean Fornasiero and John West-Sooby’s recent anthology, Roaming freely throughout the Universe (Wakefield Press, 2022). Falkiner forgoes the opportunity to focalise her story closely through either Rose’s own vivid and personable firsthand accounts, or even Louis’s, in favour of a sweeping and distant third-person approach. Rose’s voice is largely paraphrased and swamped by the volume of male voices. Falkiner’s approach makes it difficult to critically interrogate or compare the shifting perspectives of different narrators or to maintain a strong narrative flow, limiting the reader’s engagement with the protagonists’ emotional journeys. Rose herself remains distant throughout the book. Her untimely death from cholera, for example, is swiftly noted in a few lines before the narrative sweeps on with a discussion of Louis’s financial difficulties in publishing his narrative of the Uranie’s tour du monde.

The journey of Louis de Freycinet and his wife provides a fascinating insight into our often overlooked French–Australian history. Suzanne Falkiner’s in-depth account of this journey is an overdue addition to our knowledge of a voyage that is worthy of more attention and interest, as much for its unexpected heroine as it is for its strong supporting cast of characters.

Comments powered by CComment