- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Literary Studies

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: ‘Ah well, I suppose’

- Article Subtitle: The editorial challenge of <em>Such Is Life</em>

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

‘Such is life’ is a common phrase in Australian popular culture – it has even been tattooed on bodies – but Joseph Furphy’s novel of the same name, published in 1903, is often forgotten. Ned Kelly mythology suggests that he uttered this phrase just before being hanged in 1880, though some historians argue that what he actually said was, ‘Ah well, I suppose’. Long before Furphy (1843–1912) wrote his magnum opus, the stoic phrase was perhaps wrongly associated with a cult hero’s execution.

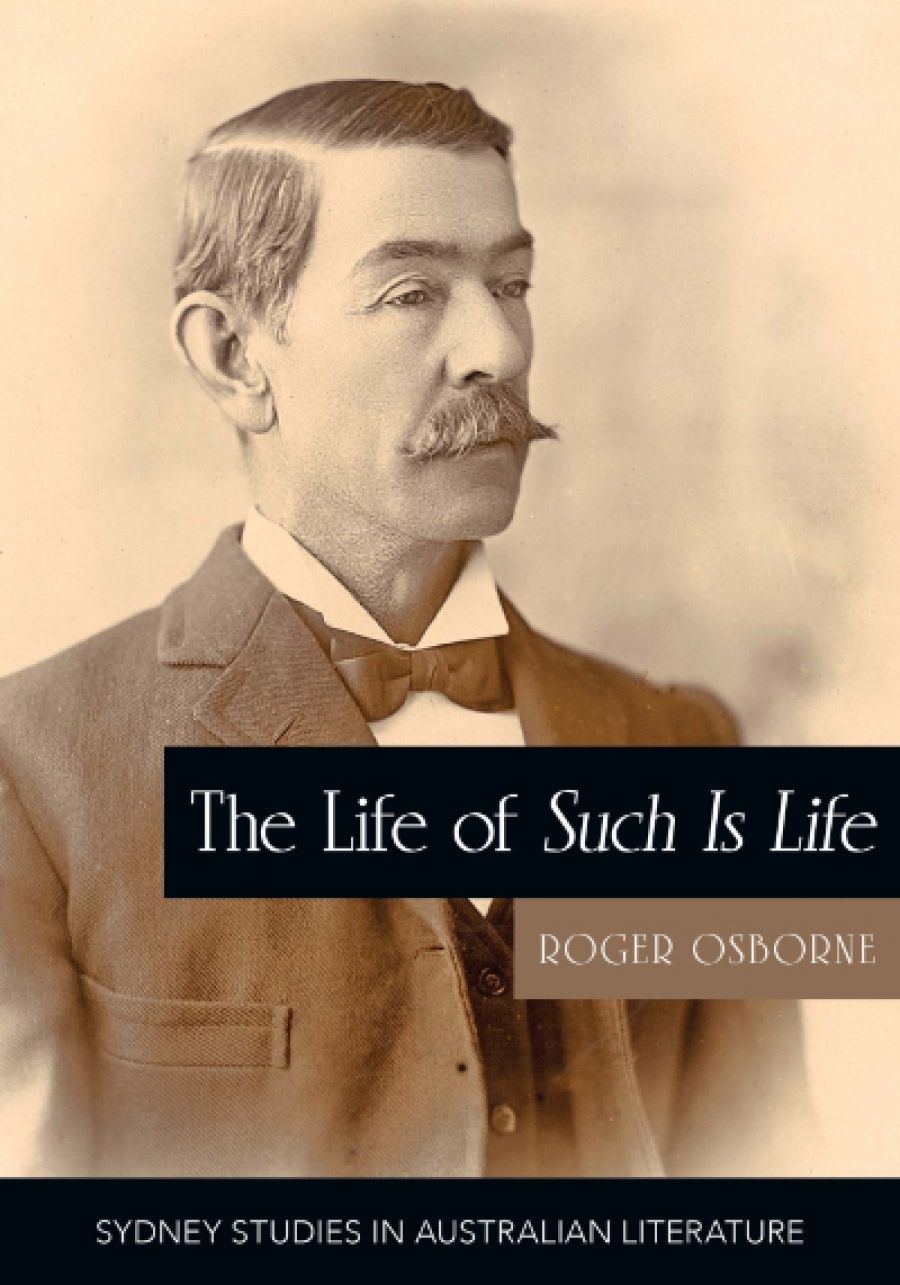

- Article Hero Image (920px wide):

- Article Hero Image Caption: Joseph Furphy, 1903. (From Miles Franklin’s photographs of friends, c.1897–1942, from the collection of the State Library of New South Wales via Wikimedia Commons)

- Alt Tag (Article Hero Image): Joseph Furphy, 1903. (From Miles Franklin’s photographs of friends, c.1897–1942, from the collection of the State Library of New South Wales via Wikimedia Commons)

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Brigid Magner reviews 'The Life of Such Is Life: A cultural history of an Australian classic' by Roger Osborne

- Book 1 Title: The Life of Such Is Life

- Book 1 Subtitle: A cultural history of an Australian classic

- Book 1 Biblio: Sydney University Press, $45 pb, 204 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/0JobdY

Roger Osborne, a senior lecturer at James Cook University, has been working on Furphy’s manuscripts for more than a decade, producing a digital archive along with this book. Osborne has previously argued that Such Is Life has a pivotal place in the development of Australian literature, occasionally wandering on to centre stage, demanding to be heard. Depending on your perspective, it might be read as a realist depiction of bush life or a proto-modernist text that resists interpretation.

The time is right for a study of this classic’s ongoing resonance. The last surge of Furphy publications happened in 1991 with the release of Julian Croft’s The Life and Opinions of Tom Collins: A study of the works of Joseph Furphy and The Annotated Such Is Life, edited by Frances Devlin-Glass, Robin Eaden, Lois Hoffmann, and G.W. Turner. In 2012, a conference was held in Shepparton to mark the centenary of Furphy’s death, followed by a special edition of the Journal of the Association for the Study of Australian Literature (JASAL).

After a career driving bullocks in the Riverina, Furphy set to work on an ambitious literary work while employed at his brother’s foundry in Shepparton. In May 1897, he sent three parcels of manuscripts to A.G. Stephens at the Sydney Bulletin, beginning a six-year-long process of editorial intervention before the book was published in a vastly different form. Osborne shows us the stages it went through, from yarns ‘loosely federated’ in exercise books to the revised typescript, created on a Franklin typewriter, now kept at Tom Collins House in Perth. Under pressure from the Bulletin, Furphy changed ‘the centre of gravity’ of the novel by replacing two long chapters with new ones. The discarded elements formed the basis of subsequent publications Rigby’s Romance (1921) and The Buln Buln and the Brolga (1946).

Osborne offers a cogent chapter-by-chapter breakdown of the major revisions, excisions, and textual transfers, and of their effects on the material condition of Such Is Life. In chapter three, Osborne provides a graphic representation of the movement of text to typescript pages in the period 1898–1903, supporting his contention that broader forces were brought to bear on Furphy’s text (encouraging such drastic measures). Initially, Furphy communicated with his friend William Cathels, an autodidact like himself, but once it was submitted, ‘the boys of the Bulletin’ shaped his sense of the ideal reader of his novel, and what was deemed necessary to meet their expectations. At times, the discussion is very technical and may well be skimmed by many readers except for dedicated textual scholars or Furphy-ites. But it is crucial to Osborne’s contribution to the history of this idiosyncratic book.

He starts this monograph by announcing that he originally approached the book as an editorial challenge. But then he realised the near-impossibility of producing a truly definitive version of this text. As he says: ‘determining which version of Such Is Life best presents the work to readers of the present day presented me with significant challenges.’ His solution is to introduce readers to a network of their peers from the past and to see all the manuscripts of Such Is Life, and its offshoots, Rigby’s Romance and The Buln-Buln and the Brolga, in one place in the Joseph Furphy Digital archive available through the AustLit database. The raw materials Osborne uses for the archive are the 415 extant pages from those Furphy gave Stephens in 1898. These pages have been transcribed (with colour-coded additions in blue and deletions in red), and a small number of textual notes are provided to indicate textual transfers between chapters or important textual cruxes. This format allows us to get up close enough to see alterations at a glance, without painstaking matching and reconciling.

Having struggled with Furphy’s textual legacy myself, I was curious to find out what Osborne thinks about the different editions, such as the controversial 1937 abridged edition by literary critics Vance and Nettie Palmer (though only Vance’s name appears on the cover as an editor), which was widely panned. In 2013, Croft observed that ‘an attempt to retore a text [of Such Is Life] as close as possible to the “original”, no matter if problematic, would be generally welcomed’. Rather than seeing one version as being preferable to another, Osborne regards the text as being in a constant process of becoming, changing according to the interests of the custodians of each time period. The patterns of literary sociability that surround the text are more crucial for him than making definitive judgements about the value of these past editing practices. For contemporary readers, there are problematic elements in Such Is Life, most notably the depictions of women and First Nations people. Osborne registers recent scholarly reappraisals while emphasising the continued relevance of Furphy’s text.

Rigby’s Romance – ‘the socialist core’ of Such Is Life, ‘sugar coated with the sweetest romance you ever struck’ – was one valuable by-product of Furphy’s strenuous editing. Osborne traces what happened to Rigby’s Romance when it was published in Broken Hill’s Barrier Truth – now known as the Barrier Daily Truth – with no financial recompense for the author. He notes that it is extremely difficult, more than a century later, to gauge the impact of a serial on a reading community. Surviving evidence suggests that it was read eagerly by workers, especially miners who used it as a pretext to debate aspects of socialism. Although Furphy’s desire was for Rigby’s Romance to be published as a book, this serialisation allowed it to reach readers in a more immediate way, on the front page of the Barrier Truth. This aligns with John Barnes’s call for ‘studies of Furphy [that] look more closely at Such Is Life as a cultural creation’.

In 1921, Kate Baker, Furphy’s indefatigable standard-bearer, rescued Rigby’s Romance from the files of the Barrier Truth and entered it for the De Garis Novel Competition. It received an honourable mention and was subsequently published. But for Baker’s passionate advocacy, Such Is Life may not have had the longevity it has – she was responsible for many of the events and decisions that eventually established it as a classic.

In this scholarly study, Osborne locates himself at the ‘tail end’ of a 130-year history in which Such Is Life was a ‘touchstone’: a literary work which has embodied divergent cultural meanings. Next to the epilogue is a photo of the author resting under the Joseph Furphy Memorial Tree, which still stands in the Melbourne Botanical Gardens. Osborne is entirely invisible in the shadows. This seems appropriate, given his light touch when it comes to charting the vexed textual history of Such Is Life.

Comments powered by CComment