- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Politics

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: All about Malcolm

- Article Subtitle: Liberal loathing of one of their own

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

When out of government, the Coalition parties resemble nothing so much as an ill-disciplined horde, by turns bombastic and bilious, riven with discord, forever tearing down putative leaders and searching for scapegoats to explain their losses and lot. The blame almost always falls on the departed. In the 1980s, it was Malcolm Fraser’s unwillingness to undertake proper economic reform that they most decried; after 2007, it was John Howard’s refusal to relinquish the leadership to Peter Costello. In Aaron Patrick’s new book, Ego, the blame is laid not at the feet of Scott Morrison, as might have been expected, but at those of Malcolm Turnbull.

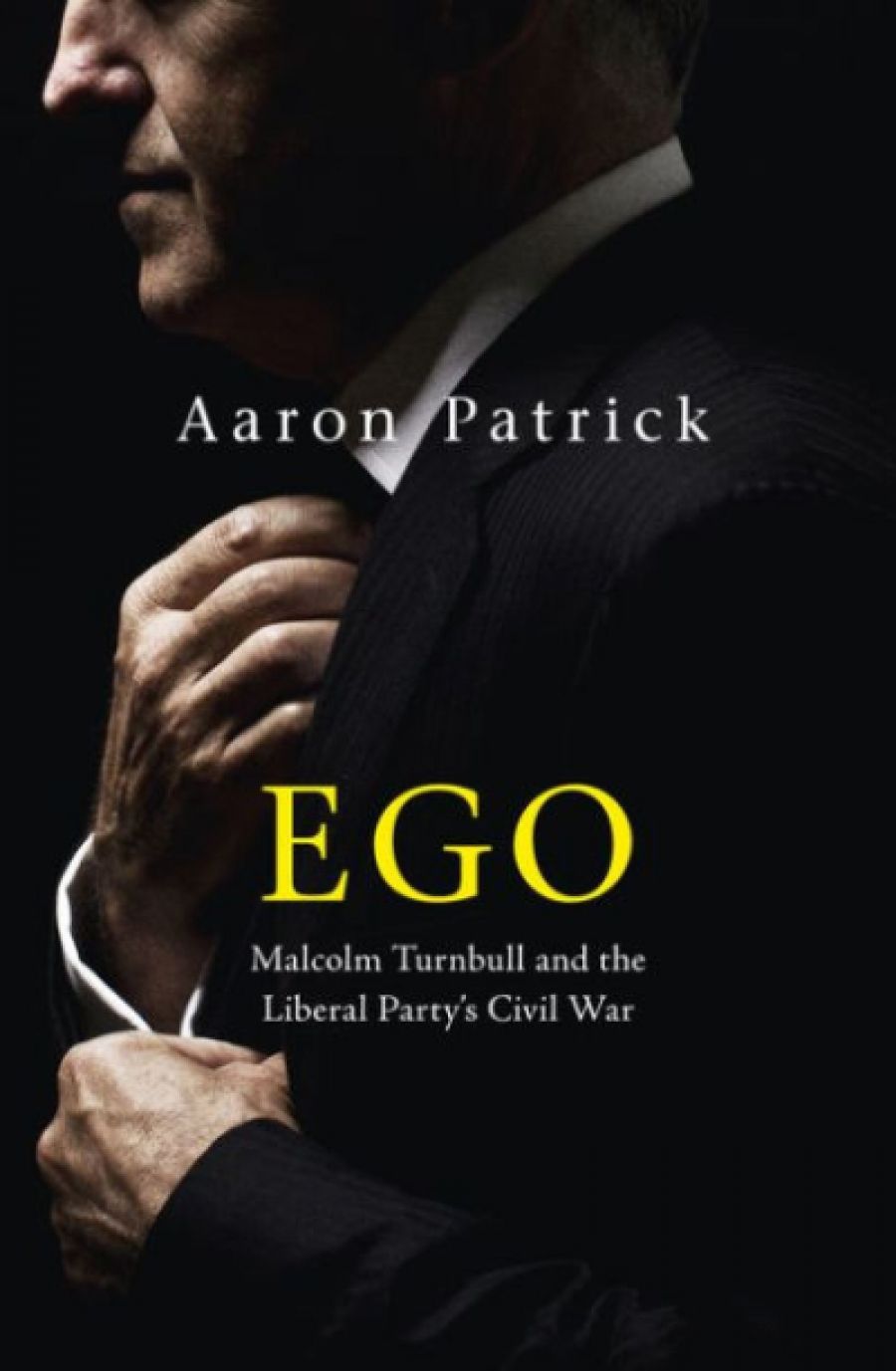

- Article Hero Image (920px wide):

- Article Hero Image Caption: Former prime minister Malcolm Turnbull (photograph via MediaServicesAP/Alamy)

- Alt Tag (Article Hero Image): Former prime minister Malcolm Turnbull (photograph via MediaServicesAP/Alamy)

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Patrick Mullins reviews 'Ego: Malcolm Turnbull and the Liberal Party’s civil war' by Aaron Patrick

- Book 1 Title: Ego

- Book 1 Subtitle: Malcolm Turnbull and the Liberal Party’s civil war

- Book 1 Biblio: HarperCollins, $34.99 pb, 336 pp

A writer for the Australian Financial Review, Patrick has authored book-length accounts of the rot at the heart of the last Labor government (2007–13), of the dysfunction of the prime minister’s office under Tony Abbott (2013–15), and of the shock delivered by the 2019 re-election of the Morrison government. He is an experienced observer of the federal political landscape, if also one who, in recent years, has become better known for his contrarian views, some of which find voice in this expansive and tendentious volume.

According to Patrick, Turnbull, after losing the prime ministership in August 2018, engaged in a sustained campaign to undermine his successor: ‘He plotted and schemed, applying his enormous energy to the destruction of the Morrison government.’ This energy was most palpable during controversies around the treatment of women and issues of sexual harassment, during the government’s self-torturing attempts to simultaneously do something and nothing about climate change, and over Australia’s ill-fated submarines deal with France. In Patrick’s view, Turnbull evinced a naked hostility towards his party and former colleagues that is without parallel in Australian political history.

There can no doubt that Turnbull was a notable critic. His command of public attention and his willingness to speak bluntly about the government’s failings, especially to left-wing audiences, helped him to recover some of the stature he had lost in office. And whether it was on the allegations against Christian Porter or the government’s candour with the French, Turnbull offered commentary that was articulate, scathing, and entertaining to boot. Having dismissed Kevin Rudd and Abbott as ‘miserable ghosts’ for their ongoing engagement with political debate in post-prime ministerial life, Turnbull’s own engagement represented a notable about-face, of which some have been rightly critical. And, to be fair, Turnbull’s commentary was not always judicious. Turnbull’s speculation about the circumstances of the suicide of Porter’s accuser was ill judged, and his calls for an integrity commission rarely acknowledged that he had resisted similar calls while in office.

In some instances, too, Turnbull’s pressure was efficacious. Porter’s decision on 3 March 2021 to out himself as the minister accused of historical rape offences came only a few days after Turnbull gave great publicity to the allegations by speaking about them at a writers’ festival and on ABC radio. And Turnbull’s attacks on Morrison’s character – ‘He’s lied to me on many occasions,’ he told journalists – certainly contributed to the growing distrust of Morrison’s authenticity and honesty.

But apportioning responsibility for the Morrison government’s woes is hardly as simple as this book suggests, and despite Patrick’s best efforts Turnbull appears more as an agitator, not an instigator, during the cavalcade of scandals and controversies that erupted between 2018 and 2022. It was Morrison’s constant resort to the tone-deaf platitude that saw issues around sexual harassment and the treatment of women become so potent. It was the government’s unwillingness to establish an inquiry to delve into the Porter allegations that allowed them to become so heated. It was the government’s diplomatic ineptitude that provoked France’s hostility when the AUKUS arrangements were announced. It was the government’s internal disunity that crippled any meaningful action on climate change. And it was the government’s failure to attract talented women into its ranks and deal successfully with the issues near and dear to inner city electorates that saw a swath of Liberal heartland seats fall, in May 2022, to the Teal independents.

At the heart of this book is a question about loyalty: to the public, to the country, to party, to institutions, to movements. Should Turnbull, for partisan interests, have muzzled his views on issues in which he had a longstanding involvement? Should he have curbed his desire for revenge on former colleagues? Patrick suggests the answer is yes, if only for the Liberal Party, which gave Turnbull a seat in parliament and then the prime ministership.

‘It had given him the prize he had always sought. It expected, and later hoped, forlornly, for loyalty in return.’ And yet, as Turnbull, sharply, replies: ‘The Right believes in loyalty until it doesn’t suit them, and then they blow the place up.’

For all the heat and light directed at Turnbull, what Ego most sharply illuminates – perhaps unwittingly – are the fevered prejudices, petty vanities, and self-interested paranoias shared by members of the former government. Josh Frydenberg can ‘command access to millions of television cameras, almost at will’, Patrick writes, yet he is upset when junior colleagues fail to retweet his ghost-written banalities. The current deputy leader of the Liberal Party, Sussan Ley, blames Turnbull for her 2017 resignation as health minister: it was not her blatant misuse of travel entitlements but his desire for clear air that was pivotal. Former Defence Minister Linda Reynolds called someone a lying cow but thinks the insult is mitigated by context and regards herself as a victim. The Liberal Party’s right wing thinks Porter a ‘martyr to the cause of conservatism’, no matter that he decided of his own volition to retire from politics.

Perhaps most notably, the sustained barrage of controversies led members of the government to perceive a ‘conspiracy’ at work to destroy the Coalition’s hold on power, with Turnbull a central figure. Patrick appears to have gulped the Kool-Aid. References to the possibility of informal alliances, too striking coincidences, and unrevealed connections abound. The publisher of Turnbull’s score-settling autobiography is also the publisher of a polemic on the Morrison government’s ‘lies and falsehoods’. Turnbull, prompted the opening of Guardian Australia, an outlet frequently critical of the Coalition. It was also the home of Katharine Murphy, one of a handful of female journalists regarded by the Coalition as enemies because of their coverage of the government’s issues with women and sexual harassment. Patrick does not repeat his much-criticised 2021 claim that these journalists produced ‘angry coverage that strayed into unapologetic activism’, but his account of their work is sceptical.

We can harbour reservations about efforts to apportion all the blame for the May 2022 election defeat to Turnbull. Despite Patrick’s claims that ‘it was all about Malcolm’, that he was ‘the shadow figure’ in all its misery, that he was ‘at or near the heart of the conspiracy’ to cast the Coalition from office, the truth is simpler. A government long in the tooth, bearing the scars of bitter leadership battles, prolonged instability, and division, staring at the world with a jaundiced eye, detecting enemies wherever it looked, led by a man distrusted by the broader public and denigrated by his own followers, was ultimately driven by its own demons to stampede like the Gadarene swine to the precipice of electoral oblivion – and then to plunge in.

Comments powered by CComment