- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Commentary

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: ‘The burden laid upon her’

- Article Subtitle: Australia’s policy gyrations on China

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

On 17 November 2011, President Barack Obama quoted Banjo Paterson to an audience of Australian and American military personnel at RAAF Base Darwin. He recited a question that Paterson posed about Australia in a poem he wrote to celebrate Federation in 1901: ‘Hath she the strength for the burden laid upon her, hath she the power to protect and guard her own?’ The question haunts us still. Obama assured his listeners that the answer was ‘yes’, but everything about the circumstances of his speech suggested the opposite.

- Article Hero Image (920px wide):

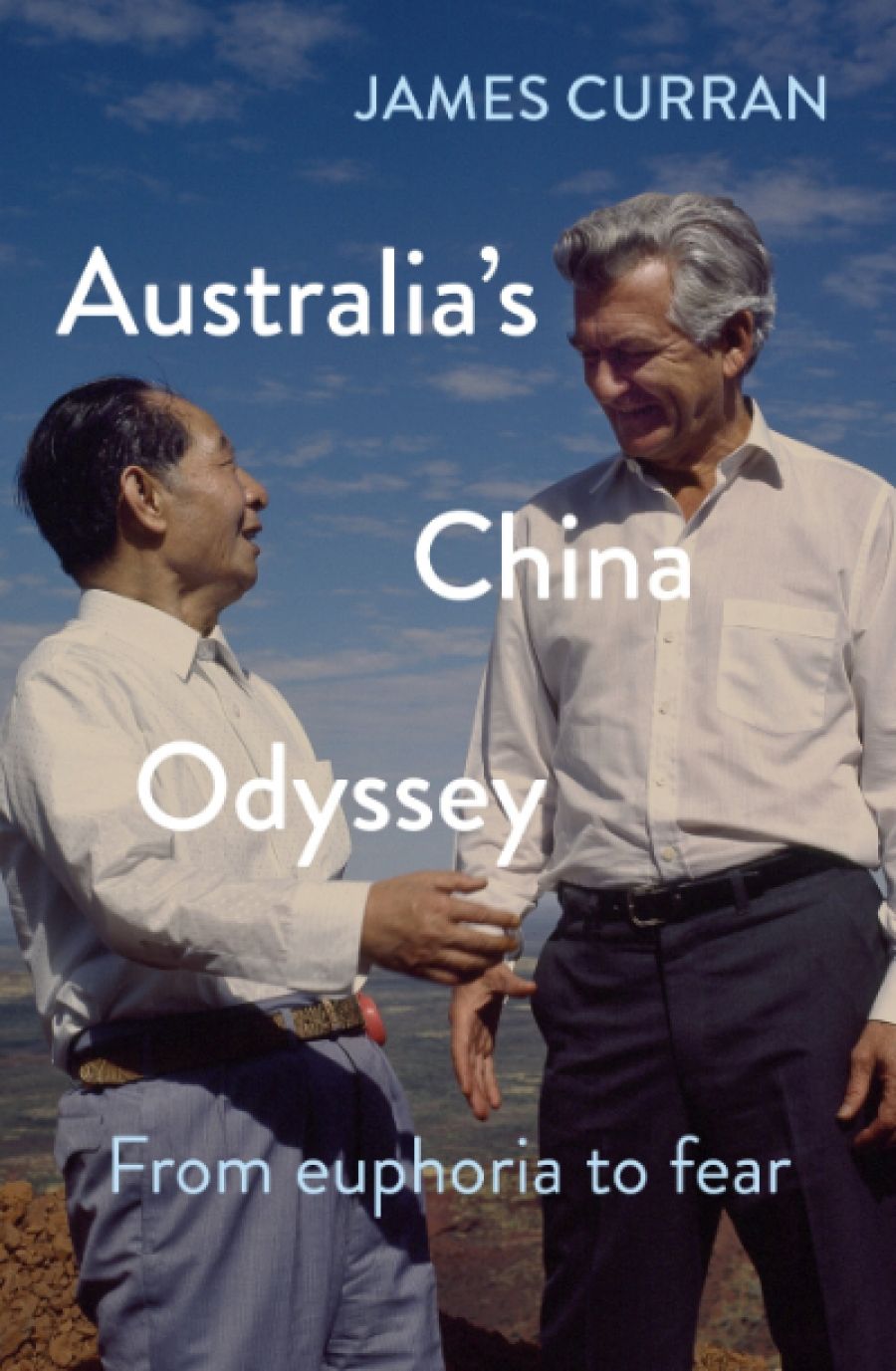

- Article Hero Image Caption: Gough Whitlam leaving Beijing at the end of his 1973 visit to China (photograph via National Archives of Australia A8746, KN15/11/73/79)

- Alt Tag (Article Hero Image): Gough Whitlam leaving Beijing at the end of his 1973 visit to China (photograph via National Archives of Australia A8746, KN15/11/73/79)

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Hugh White reviews 'Australia’s China Odyssey: From euphoria to fear' by James Curran

- Book 1 Title: Australia’s China Odyssey

- Book 1 Subtitle: From euphoria to fear

- Book 1 Biblio: NewSouth, $34.99 pb, 334 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/3PW1ok

Earlier that day, Obama had addressed a joint sitting of the Australian Parliament in Canberra to announce his administration’s ‘Pivot to Asia’. It was America’s first faltering attempt to resist China’s challenge to US strategic primacy in East Asia, and it was greeted with rapturous applause on all sides in Canberra. He and Julia Gillard, the previous day, had announced that in support of this policy US Marines would establish a permanent rotational presence in Darwin – the first permanent presence of US combat forces here since World War II.

It could hardly have been clearer that in the face of China’s rise Australia did not believe it ‘had the power to protect and guard her own’. Instead, with the marines in Darwin we were clinging closer to the United States to protect us from China. Ten years later with AUKUS, we are clinging closer still. It is strange and suggestive that the White House speechwriters didn’t see how discomfortingly pertinent Banjo’s question remained, 110 years after he posed it. Or perhaps they did.

There are many nuggets like this in historian James Curran’s rich and detailed account of the evolution of Australia’s relationship with China since the communists took power there in 1949. He is well fitted for this task, having written a number of fine books on Australia’s evolving place in the world and its relationships with Britain and America in the postwar era, as well as perceptive commentaries on contemporary affairs as a columnist for the Australian Financial Review. His work consistently demonstrates the value of well-wrought history to contemporary policy debates. The book’s epigraphs include a telling passage from the late Neville Meaney – one of Curran’s teachers, and perhaps the finest historian of Australian strategic policy – warning of the ‘uncritical mythology’ by which current events are misunderstood and policy choices distorted in the absence of a clear understanding of what has gone before.

That is certainly true of Australia’s current problems with China. Two intertwined oversimplifications – tales of Australian greed and naïveté on the one hand and Chinese duplicity on the other – distort debate about how we got into this mess and how we might get out of it. That distortion is even reflected in the subtitle of Curran’s new book (‘From euphoria to fear’), but the work itself is a powerful corrective. It gives a far more nuanced view of how generations of Australian leaders and their advisers have wrestled for decades to manage the challenges and opportunities posed by the world’s most populous country as it has undergone a series of profound transformations.

Curran starts by outlining the complex and often sophisticated debates that lay behind Menzies’ crude invocation of communist Chinese threats in the 1950s and early 1960s. He describes discussions about whether to follow the United States in denying recognition to the communist regime and how far to go in threatening Beijing militarily – especially with nuclear weapons – about which they were notably cautious. Curran then describes Gough Whitlam’s audacious overture to China in 1971, and the commendable mix of optimism and sober realism that framed the opening of diplomatic relations in the years that followed. And he unpacks Malcolm Fraser’s efforts to harness China to his surprisingly audacious efforts to build an anti-Soviet coalition in the late 1970s.

China, in those days, remained mired in Mao’s rule and its chaotic aftermath, but the potential for China to profoundly transform Australia’s strategic environment and challenge our view of our place in the world was already clear to perceptive observers. As early as 1976, our first ambassador to China, Stephen Fitzgerald, wrote of the need to develop relations with China so that ‘we may the more easily accommodate to a situation in which Chinese influence is paramount in our part of the world’ – a prospect which then seemed very distant indeed.

Things are very different in the 1980s, when Deng’s economic reforms and opening to the West gave a glimpse of China’s potential, and began to offer Australia the opportunities that would for so long transform our economic fortunes. Curran’s account of Bob Hawke’s and Paul Keating’s remarkable efforts to realise these opportunities by engaging Chinese leaders is one of the highlights of the book. He recounts how Hawke’s rapport with key figures in Beijing in these critical years was closer than that of any other Western leader’s. But Curran’s story really hits its stride when he moves on to the Howard era. Coming to power in 1996 as China’s rise was really beginning to tell, John Howard was the first prime minister to confront its complex implications head-on. On the one hand, China’s growth of ten per cent per annum year after year offered Australia quite extraordinary economic prospects. On the other, that growing wealth gave China the power – if it chose to use it – to challenge the US leadership in Asia on which Australia’s security depended. From his first weeks in office, which coincided with the last major US–China military confrontation over Taiwan, Howard sought ways to harness China’s rise to drive our economy while preserving the US alliance and upholding American regional primacy.

Ever since – for more than twenty-five years – that has remained the primary challenge to Australian foreign policy. The story of how that challenge has been conceived and addressed by successive governments forms the heart of Curran’s book. He gives a fascinating and detailed account that shows the sheer inaccuracy of the image of Australia as simply greedy, complacent, and naïve before suddenly waking up to Chinese perfidy in 2017.

Curran recounts Howard’s artful positioning, neatly symbolised when on two consecutive days in October 2003 he hosted both the US and Chinese presidents – George W. Bush and Hu Jintao – to address our parliament. He describes how Kevin Rudd’s fluency in Mandarin became a liability rather than an asset in dealing with both Beijing and Washington. He explains Julia Gillard’s successes in rebuilding both relationships, and describes Tony Abbott hailing Xi Jinping as a champion of democracy, just a few days after telling Angela Merkel that our relationship with China was built on ‘fear and greed’.

Curran’s blow-by-blow account of all this is comprehensive, engaging, and very valuable. It does, however, have the weaknesses of its strengths, because all the fascinating detail can tend to occlude the bigger questions that our policymakers really need to address. These concern the three assumptions that have underpinned all the political and policy gyrations since 1996 that Curran so fluently describes.

First, we have consistently underestimated China’s power and resolve. In the face of abundant evidence, we have too easily assumed that China’s economic rise would wane, that its political system would falter, that its technology would lag, that its military power would remain uncompetitive, and that it had no real interest in challenging US power. Second, we have consistently overestimated US power and resolve. In the face of equally abundant evidence, we have too easily assumed that America would remain unchallengeable economically, technologically, diplomatically, and militarily, and that it would remain committed to doing whatever it takes to preserve its leading position in Asia and globally.

These failures of assessment have together led us to assume that America would solve our China problem for us, by ensuring that we never had to, in Fitzgerald’s words from 1976, ‘accommodate to a situation in which Chinese influence is paramount in our part of the world’ – whereas that seems to be precisely what we now have to do.

The third constant is that since 1996 we have too easily taken for granted that accommodating to Chinese hegemony in our part of the world is something we simply cannot do. This is part of Howard’s legacy. He often said that Australia would never have to choose between its history and its geography. That was his way of expressing his faith that our historical friends – our Anglo-Saxon friends – would always and must always shield us from our geographical neighbours. It is a faith that took deep root and has been maintained by his successors on both sides of politics ever since.

That faith overturned an idea that had been slowly gaining ground among Australians for fifty years before 1996: the idea that eventually we would and could and should find our way in an Asia that was no longer dominated and made safe for us by Anglo-Saxon powers, but was instead dominated by Asian powers. Almost sixty years ago, Donald Horne explored this idea in The Lucky Country. Hawke and Keating expressed it when they said that Australia must in future look for its security in Asia, not from Asia.

But Howard killed it, and it has never been revived, so that today some of our political leaders argue that we should go to war with the United States against China – a war that we cannot win – rather than face the challenges of making our own way in the Asia of the twenty-first century without America’s support. To them, and I fear to many others, the answer to Banjo Paterson’s question – ‘Hath she the strength for the burden laid upon her, hath she the power to protect and guard her own?’ – is still ‘no’. We need to prove them wrong.

Comments powered by CComment