- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Cosy crime

- Article Subtitle: Benjamin Stevenson’s entertaining third novel

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Enid Blyton’s Secret Seven series (1949–63) was my induction into crime reading. I was smitten with the secret society of children who set out to solve mysteries and right wrongs despite adults’ disbelief and objections. As a teen, I graduated to Agatha Christie and Arthur Upfield (in the 1970s, we were still unaware how offensive his depiction of Detective Inspector Napoleon ‘Bony’ Bonaparte was to Aboriginal Australians). Later, came writers of the hard-boiled school – Raymond Chandler, Dashiell Hammett, Chester Himes – and others, like Georges Simenon and James Ellroy, who extended or subverted the conventions of the genre.

- Article Hero Image (920px wide):

- Article Hero Image Caption: Benjamin Stevenson (photograph by Monica Pronk/Penguin)

- Alt Tag (Article Hero Image): Benjamin Stevenson (photograph by Monica Pronk/Penguin)

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Francesca Sasnaitis reviews 'Everyone in My Family Has Killed Someone' by Benjamin Stevenson

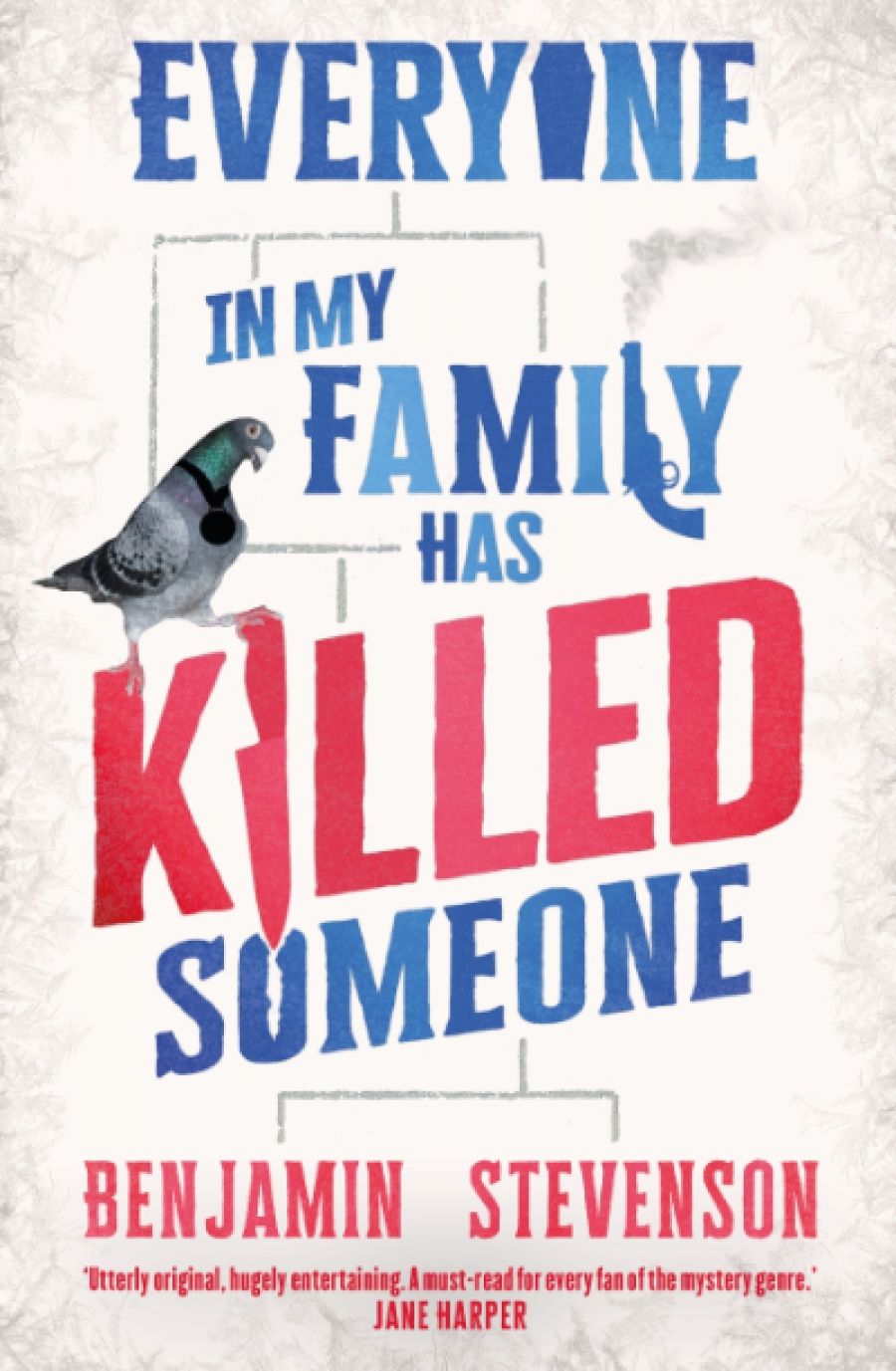

- Book 1 Title: Everyone in My Family Has Killed Someone

- Book 1 Biblio: Michael Joseph, $32.99 pb, 371 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/KeGeGn

Benjamin Stevenson declares his affinity with the golden age of detective fiction (1920s and 1930s) in the epigraph to Everyone in My Family Has Killed Someone: the membership oath of the Detection Club whose august signatories included Christie, G.K. Chesterton, Ronald Knox, and Dorothy L. Sayers. Knox’s ‘10 Commandments of Detective Fiction’ (1929) follows. The narrator, Ernest Cunningham, urges the reader to dog-ear the page and swears he will abide by those rules. Cunningham is a writer not of detective fiction but of books on how to write. He assures us that ‘this isn’t a novel’, moreover that he is a ‘reliable narrator’ who will make every effort to relate the truth as he understands it at any given moment. He even provides the eager gore-seeker with the numbers of the pages on which deaths will occur.

As one might expect from a comedian, Stevenson’s third foray into crime fiction is terrific fun. The title alone invites comic disbelief, but readers should be on their mettle and remember that ‘killed’ is not the same as ‘murdered’, that every allusion is significant, and that the English language is marvellously given to misinterpretation. If Ernest/Ernie/Ern leads us astray, it’s not his fault: he never promised to be competent in the role of either sleuth or writer.

Ernest has been ordered by his formidable aunt to attend a family reunion at an alpine resort; he is not looking forward to it. Why he has long been estranged from his notorious family (don’t make the mistake of thinking ‘Kath Pettingill’) will be explained. The isolated setting and limited group of suspects recalls Christie’s The Sittaford Mystery (1931) and Hercule Poirot’s Christmas (1939), especially after a storm hits and Ernest’s initial trepidation is justified by the discovery of a man’s body in the snow. No one knows how he got there – the number of tracks leading to the corpse doesn’t match those heading away – nor how he died – he appears to have been incinerated but there is no evidence of a fire. No one recognises him, no one from the resort is missing, and none of the family has links with the deceased. We are led to believe that no one is lying. Suffice to say that Ernest, or rather Stevenson, is expert at meting out unexpected revelations (while sticking to the ‘10 Commandments’), like the name of a victim who has police connections at the end of Chapter 26.

Ernest’s narrative is divided into sections devoted to each family member – brother, stepsister, wife (a hilariously succinct chapter), father, mother, stepfather, aunt, sister-in-law (former), uncle – everyone a killer in their way, including Ernest; each section progresses towards understanding the complexities and consequences of misplaced motivation.

If the reader has not been paying sufficient attention, Chapter 14.5 offers a handy recap – backstory, location, cast – and a list of significant plot points, including advance notice of the next death. Throw the possibility of a serial killer into the mix and you have a classic whodunit with more twists than a hangman’s rope. Although I’m not partial to details of serial killers’ gruesome appetites, Stevenson’s nod to Christie’s And Then There Were None (1939) is forgivable.

Another half-chapter (27.5) begins with ‘This is not a spoiler’ and proceeds to dissect the ‘book as physical object […] which can betray a few secrets the author does not intend’. In other words, pay attention not only to the dribble of information but to ‘section breaks; blank pages; chapter headings […] there are clues in every word – hell, in every piece of punctuation’. Most readers will be familiar with the self-conscious diversions of metafiction. Ernest’s apologies to his editor are a clever way of highlighting ungrammatical or clichéd usage while signalling that those choices are deliberate. But his frequent authorial interpolations can be exasperating: ‘The phone rang. Of course it did. You’ve read these kinds of books before.’ Others are more subtle: ‘There is only one plot-hole you could drive a truck through.’ The narrator says, ‘Trust me’, but trust me, I didn’t deduce half of what I should have, at least not until Ernest reiterates the clues he used ‘to put it together’ fifty-three pages before the end.

Classic crime writing is the comfort food of the genre, guaranteeing a righteous resolution, an exotic (or unusual) locale, and a charming if flawed detective. Everyone in My Family Has Killed Someone fulfils the criteria of ‘cosy crime’; certainly, self-deprecating Ernest Cunningham is as endearing as Shane Maloney’s shambolic investigator Murray Whelan (1994–2007). What Stevenson adds to the mix is a larrikin quality particular to great Australian shaggy dog yarns, like Joseph Furphy’s farcical Such is Life (1903) and Steve Toltz’s A Fraction of the Whole (2008). And, like other crime writers who use the conventions of the genre to lay bare more earnest truths, Stevenson undermines the role of hero in his novel by declaring that in real life, where nothing is black and white, heroes are irrelevant. It’s the peripheral characters who bear the burdens of misfortune and injustice, ‘so someone else can raise their arms aloft in victory’.

Comments powered by CComment