- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Calibre Prize

- Custom Article Title: This woman my grandmother

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: This woman my grandmother

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

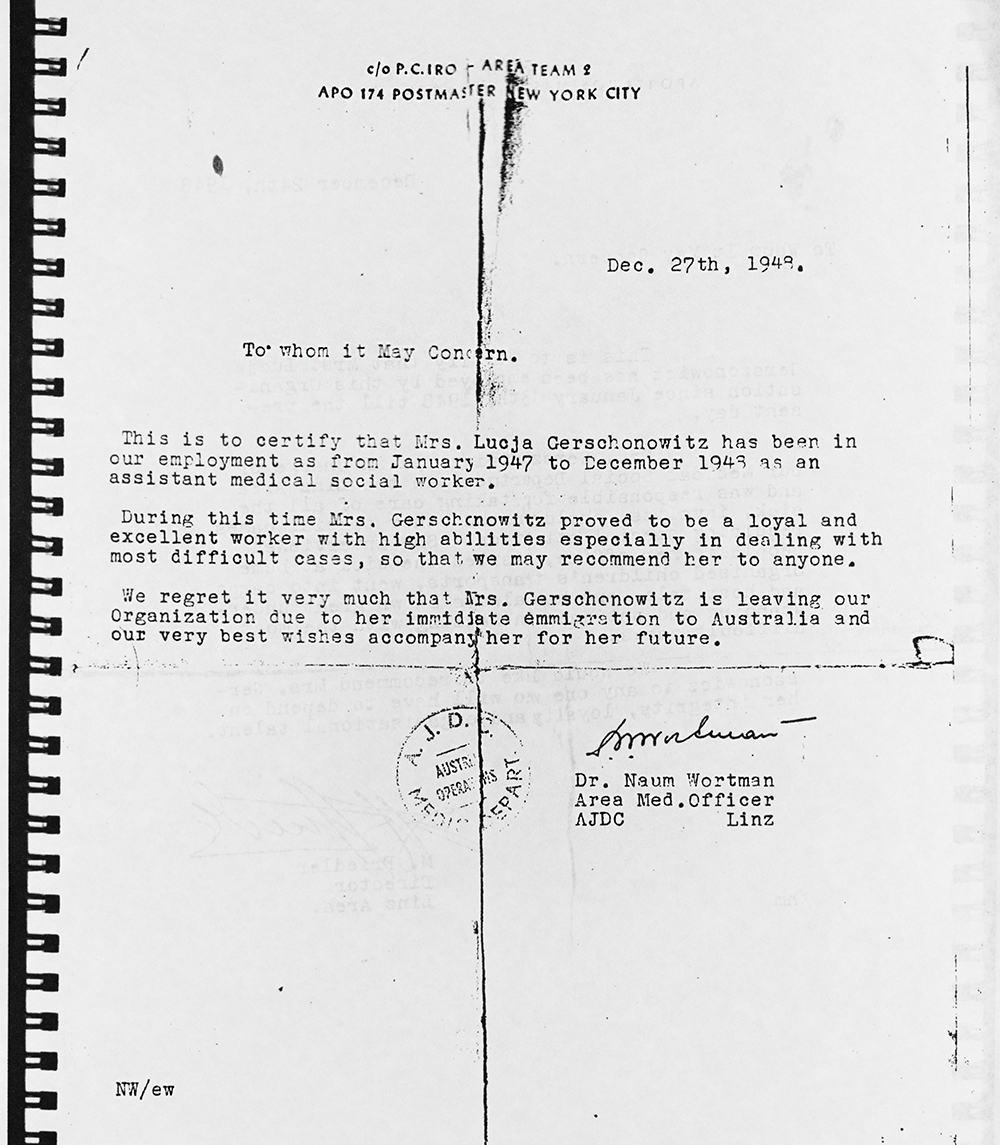

A decade before she died, my grandmother Lucy, whose Hebrew name was Leah but who was known to us as Nanna, decided to write her memoirs. English wasn’t her first language, let alone her second or third, so rather than write she chose to speak. When she was finished, the contents of eight cassette tapes were typed up and bound in blue plastic covers. Copies were made for both daughters and all five grandchildren, of whom I am the eldest.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): 2022 Calibre Essay Prize (Winner): 'This woman my grandmother' by Simon Tedeschi

A century ago, Ludwig Wittgenstein wrote the Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, a work concerned with the fundamental paradox of language – that some things can never be said, only shown. Every poet has encountered this impasse, this impermissibility – pushed hard enough, language buckles beneath our feet.

Fifty years later, in his Book of Questions, a three-volume work straddling poetry, prose, essay, and exegesis, Edmond Jabès wrote six words that read like six million – I will remain silence and scream.

Of the survivors that I knew, there were those like my grandmother’s nephew Szymon who kept silent. This doesn’t mean that they didn’t scream, only that we couldn’t hear. Szymon became what the military calls a grey man, someone who survives by fading into the background. But my grandmother, more orange than grey, was someone for whom speaking, weeping, pleading, and scheming was a riposte to the inability to say anything at all. Beneath every threat to swallow pills, every hole gouged in the wall during a fist fight with her eldest daughter, every threat to wipe both her daughters from the latest will, was the ravening silence of someone who may in fact not have survived after all.

For the first time in twenty-five years, I gave myself to my grandmother’s words. I read her in one sitting, in my own home, my own office, my own chair. But I might as well have been sitting on her lime-green couch, rudderless against the salty air buffeting in from the balcony. When it came to ‘those’ six years, Nanna was flat and factual, speaking with the cold violence of observation, a spiky music broken up with rests and reprieves, each word carefully weighted like a system of pulleys and pistons. Hans Frank seen through her window. Soldiers in the street.

A rabbi’s beard wrenched from his face. The Red Army with their bayonets and beer. Her mother, father, brothers, sisters, even a two-year-old nephew – destroyed. My grandfather, barely alive but still moving, a faded stencil of a once great work of art, a whisper cast adrift.

This was how she spoke to those she loved. The loved one in this case would have been my father, her son-in-law, a kind and fastidious man with an obsession for the preservation of memory, who, in the final years of the twentieth century, recorded the old woman’s voice in the hope that her memories, told so often that the telling itself became a kind of grim ritual, would resist the inviolability of time – that consigned to paper, hell might stay hidden.

I was liberated by the Russians on the 16th of January 1945. Seventeen pages later – the tragedy of my life. In between these two sentences, the first and last, are all the words my mother heard from the time she was a tiny girl until she left home aged twenty-four to marry my father, by which time they were her words as well. It is these same words that my grandmother told her grandchildren, who, fatigued, stopped up their ears; the same words she told to those visiting the Sydney Jewish Museum, who wrested them open, entranced by the little woman’s power to hold a room in thrall to the truth.

If the truth is merely a set of discrete facts, recounted with the quiet stolidity of a list, what Nanna wrote in her memoirs is what happened. Wife. Prisoner. Drifter. Refugee. Worker. Mother. Widow. Grandmother. This is what happened, in the same manner that I might relate what I did yesterday, if I (wish to) remember. But if my grandmother’s need to never forget is both an insistence on what is and a howl against what is not and can never again be, what can be said of what is not there? If something is deliberately left out, what becomes of the rest? What if this missing piece is, by virtue of its enormity, unable to be noticed, like a piece of grey lint in an orange room?

Hidden within her words, her croaks and cries, rests and reprieves, lies a great, famished absence.

By the time war broke out, she was already twenty-four, the same age as my mother when she was allowed to leave home. But try as I might, I simply couldn’t imagine my grandmother as a twenty-

four-year-old woman, a fourteen-year-old girl or a four-year-old child. Did she fight with her siblings? Who were her friends? What made her laugh? Was there even a time before she was Mum or Nanna?

Why do you ask? she might have snapped, had she still been alive. For a woman too stricken to speak, each word swollen and portentous with meaning yet at the same time drained, my grandmother remained absolutely silent about the period before the war. Of this life, not the past but the past past, that which happened before what happened, there exist only traces, tiny vesicles of memory that with the passing of time, in the absence of a truth-teller, will simply fade away.

Jabès wrote his Book of Questions in Paris. But when history was torn in two, he was still in Cairo, the city of his birth. As such, his writing is preoccupied with questions of sound and silence – how can a writer express what can neither be described nor denied? How can one sound the abyss from afar? Whose duty is it to speak? If the survivor is silent, must the bystander speak? How can one bear witness over distance?

Even if I had asked her more, what could she have said? If she had told me a little of her life in the shtetl, what good would it have done? Wittgenstein said of his propositions that the reader must throw away the ladder after he has climbed up it. The Tower of Babel may in truth have been people speaking in the same tongue but still not understanding each other, say, a little orange woman shouting at a grey man, or a boy with blue eyes who thought it was all a game. Proust showed that, stripped of sensation, a memory simply recounted is a great, dead thing, a signpost flapping in the wilderness. We are each of us trapped behind this wall of our eyes. How much worse must it have been for this woman my grandmother who came from a mode and manner of life that no longer exists?

No words for the sight of a grandchild in your apartment, skin unmarked by sun or snow, perhaps cross-legged or lying down on the carpet, sniggering at strange words in an arcane language or simply bored, while you bear the traces of grief, devastating and dull? I should have asked her more, but I wouldn’t have dared. I’ve never been one to speak up. She was liable to bite back at any question she considered impertinent or irrelevant, as if words could be wasted as easily as a piece of tatty cloth. For this woman my grandmother there could have been neither telling nor showing, only the void, not the one we all teeter close to from time to time or the one Schubert wrote songs about, but a perfectly passionless, grey void where normal, clever, cultured people destroyed other normal, clever, cultured people with the quiet, steady, equable hum of a machine.

From when she was young, my mother’s role with her own mother was to be a kind of involuntary poet, holding words and phrases in reserve, teasing out silences so that a composite of sorts might emerge, with perhaps enough space to adduce a shape of some kind. A few times over the course of fifty years, after a meal, all the dishes packed away as tightly as a secret, kids fat with food, my grandmother, in a rare moment of vulnerability, might have said some things here and there to my mother. She spoke of her father, a farmer. When his first wife died suddenly, a shidduch was made with a much younger woman, my great-grandmother, whose own father was a rabbi. His father too was a rabbi, so too his father, and so on and so forth for as long as words have held memory captive, in townships now obliterated but that once quivered with the tactility of daily life and that, if understood as a body, had as its navel the teacher, a man whose eyes conspired with the sky, for whom a grunt or the upturn of a single eye connoted the entire mystery of existence, for whom the Word, cast adrift into the air, could go no further so curled back on itself, for whom the very act of reading was as a lover to his bride, and stretching back even further into the misty outposts, the dusty ramparts, of time, priests and prophets, men who, struggling to explain how an infinite God could create suffering in the pure and righteous, taught Tzimtzum – that God contracted himself to make space for the world. Perhaps this is the only real way to explain how a loving parent can neglect their own children.

Of actual events, Nanna only ever said one thing, told over decades. When she was two or three, my great-grandparents might have told their daughter that she was too ugly, too hairy, or too ugly and hairy to take out in public. This is all she ever told my mother. Those who might know more are either dead or dying, and neither the dead nor the dying wish to remember.

When I knew her as my grandmother, she was neither hairy nor ugly, and in the photos I have seen – I think of one taken in Bad Gastein right after liberation – she smiles. There’s a fierceness to the way she bares her teeth, an intrepidity, that makes me think of a partisan. Around her, pressing her to his body, is my grandfather. Even though he is younger than I am now, he is almost completely bald, smiling behind chalk-cliff eyes, permeating the atmosphere with something more horrifying than horror. But that one tiny story my grandmother told my mother of a young girl who may have been severely mistreated is all I will ever know of a life lived in a world that no longer exists, muttered in the lazy recumbence of a Passover meal, sotto voce and out of sight.

Of the black blot that defaced Europe thirteen years before her birth, my mother, now a grandmother herself, cannot bring herself to read a single word. From the moment they were old enough to understand, both girls were taught that death, having come once, would come again and had in fact set himself among the furniture like an uninvited dinner guest. He sat at the dinner table and made them eat. When they were a bit older, he made mirrors look bigger than they really were. He was not only powerful but practical, obsessed with the inner workings of their bodies, a glacial horror that insinuated itself into every situation – eating, sleeping, touching, bleeding. It is chilling how this thing, whatever it is, whatever modish name it’s been given, passes through people, making paranoid incursions into our bodies, the way we all age and experience ourselves. Perhaps this is what is meant by an Adamic curse. Perhaps my lifelong love of horror movies stems from my grandmother. Perhaps what could be viewed without annihilation from the safety of a darkened bedroom could be curtailed, even contained (and many years later, a horror movie would teach me that the Ancient Greek word martyr means witness). But unlike a movie, listening to the old woman speak of her past had no real plot, only crumbly ground, the disentanglement of tightly held fantasies of cause and effect, the feeling of life ebbing away, of bodies visited by an evil spirit.

Whereas women like my grandmother commandeered their environment, seeking control of nature, transacting food the way a torturer forces water down a throat, the men of my grandfather’s generation, short and wiry, smiled sheepishly behind their spectacles, curled into corners like weevils, taking refuge in shadows, all emotions reconstituted to surface response. The muscles knew what to do. These men existed rather than lived, made noises in support of whatever was being said by the ladies at the main table, played a card game or two, laughed sheepishly at Topol or, in my grandfather’s case, read book after book (always non-fiction – he still desired to know the world).

A decade or so later, these same men – Hungarian, Polish, Russian (almost no Czechs left) – would die the same way they lived, quietly and quickly. One day – and there would be no real reason for this day over any other – a lump would be found, a chest clutched, a handrail missed. Spines would twist like cable ties, before falling silent. If you looked inside these men, you would see hearts clogged with fat wrung out from meat and crimped into even more meat, plum cake stupefied with sugar, milk sitting on a windowsill for up to a week, torpid and tumid, food so old it resisted even the forces of entropy and expansion, great dollops of sauce over everything, absolutely everything, so that each plate was sluiced in its own juices, a ravaged nightmare of concupiscence and death. The starvation had been bad enough. But what killed the men was surfeit. Like a car battery, the human heart has only a number of cycles left to it.

But the women were stronger, living on in a kind of revenge. Getting together most weeks at the club, my grandmother, never one for irony, gave them the moniker kaczki or even alta kaczki. After a drawn-out session of bridge – a game I have always been curious about but whose rules remain cloaked in a language of forbiddance (you wouldn’t understand) – they would stagger home to their beds, caked in enough makeup to make their faces seem bruised, only to wake up the next morning, pillows stained like unholy shrouds. And the fights, how they would fight, words pulsating and shuddering like dying animals, things said by those with nothing or nowhere to fall back on – such friendships, bound by blood, would end in an instant.

This woman my grandmother never said or ‘wrote’ any of these things. In public, she would speak about her late husband as if he were a man among men, even though when alive she would lament his very existence. To her friends she would boast about her daughters and grandchildren, while shaming and humiliating them when no one else could hear. In public she was a progressive, at home a reactionary. At the Museum, we would listen to her panegyrics to the One True God, though I suspect she didn’t believe in a God who had died by his own hand or simply slunk away in abject disgrace, perhaps, according to some ancient traditions, after the Second Temple was destroyed by the Romans, as an active or tacit participant in the desecration of a people who gave themselves to the world and who were, as Stefan Zweig once wrote, exterminated root and branch by way of thanks.

Many people over the years have suggested that my grandmother was a product of her trauma. Others have given her labels that can be found easily enough on the Internet. But these are rickety bridges of words. My grandmother’s nephew Szymon had a wife, also a Pole, also called Lucy, who said that my grandmother was always this way, that even before the war she was difficult, that her family of origin were obsessed with conflict. Maybe she was just a difficult woman. Maybe the war did it to her. Maybe the line between deprivation and depravation is thinner than we think. But I cannot be satisfied with diagnoses and definitions, words hollow and void, slick and alien, words that tell everything but show nothing, words that make my grandmother a type, a Mum or a Nanna, a Jewish joke, a Mrs Portnoy parsed from the page, reduced, as with the dog that can’t fetch, to function. It is futile to speculate why she was the way she was. As I have grown older, I’ve been forced, unlike her, to learn to live with uncertainty.

We can trace what happened in those six years back to the Middle Ages, the European nation-state, or even Judas betraying Christ with a kiss. But causes are a comfort blanket. Tolstoy said there are no real reasons for things. Even if there were, these are constellations, impossible to pick apart from their consequences. We will never know why some people act as they do, why others fail to, why some destinies are chosen, why others are forsaken. The only thing we can be sure of is that time appears to our eyes and ears to pass in one direction, from past to future. The present is something we feel certain is there but cannot be pinned down. Perhaps this is why Hebrew is read from right to left – an attempt to wrench back the world.

Since Nanna died, the world has yet again changed. The earth we have inherited is one in which every action, no matter how small, feels like a flutter in the planet’s pulse. Sometimes I wonder if we can no longer be innocent victims or neutral bystanders but are caught up in the world’s webbing. Around the time she gave me her memoir to read, Nanna also gave me a zachor lapel pin so that I might never forget. But I forgot where I put it. Sometimes it really feels like living is complicity.

It took me a quarter of a century to read her memoirs. Now she lies in the dirt that beckoned her home ever since her feet touched the pier, plot number twenty-one, close to her husband but not close enough for them to touch, booked and paid for so long in advance that it seemed almost hypothetical, a tombstone incised with she died of a broken heart, a sentence designed to hurt her relatives while they still lived, a plant’s prickle right in the eyes. She feared death, just as I do, and I suppose this cruelty was her way of living on, the way art is in mine. When she was in her hospital bed, I saw her eyes and knew that she was frightened, more frightened than she’d ever been, and that she hadn’t been granted that final mercy of mottled consciousness. Her last words to everyone were this is the end. I often wonder what it must have been like to know that soon she would cease to exist, that all her threats had at last come to pass.

Two years ago I spat into a test tube. When the results came, it felt like words had been stripped of meaning. Her older brother had survived Auschwitz. For fifty years the two of them, my grandmother and her brother, had lived on the same planet at the same time. He’d been a resident of Germany, a successful businessman, a theatre producer, and had even changed his first name to sound German. Twenty years ago he died, leaving behind a family, three adult children who knew nothing of what their father had heard, what his hands had touched, his eyes seen.

I wrote to all of them. We wanted to know everything, and if they couldn’t give us anything, we wanted to know the nothings. But their responses were like koans or difficult poems, as if this grey man, this German, had imparted to his family the power of stuck speech. We asked more questions. What was he like? What did he say? We were after whatever we could get – an untenanted memory, a stray statement, a toenail. If they’d told us that he was a bastard, that would have been something. But they responded with tales of bitterness and recrimination, not just from him but between them, his children and grandchildren, nicks left to fester, things said years before and cherished as evidence, great rapacious sprays of shame. Then one day, for no reason we could ascertain, they stopped replying. We tried again and again. But we never heard another word.

My mother checked the Yad Vashem. Another atom bomb. Nanna never entered her older brother’s name in the list of those who perished. There is no chance whatsoever that my grandmother, this woman for whom speaking was a right, did not know that her older brother, a prominent citizen in his German city, had survived. This woman my grandmother this keeper of tales this bearer of memory this lodestar around whom we circled like motes of dust, had kept a secret, a great, wincing secret. In her eyes, this man stricken to silence, this grey man, this German, had been both dead and alive at the same time. There are many questions but no answers. One can hazard guesses, some of which do not bear thinking about. But some things are not to be known or shown. As the holy scriptures say, we are merely glancing through the latticework.

I loved this woman my grandmother. But I couldn’t have loved her in the way she loved us. She would have laid down her life for any one of us. That was part of the fantasy in the end, that this love so engulfed her that it prevented her from fully living. She floats through space, a necklace of naked atoms, while I sit here watching my life unfold in the way it has and will, missing her more than ever, not missing her at all, only now realising that she was bigger, fuller, more expansive than I ever imagined.

Sometimes I think the reason why ghosts don’t haunt us, even though they see us grieving for them, is that the language is just too different – once you’ve realised why art is, love is, death is – why disassemble yourself? Or maybe things are just as cut and dry as the Torah says and she is just waiting for us, waiting and waiting, another hour and we might show up, maybe they had an accident on the bus or got mugged, do you see how they treat me, etc. As every Jewish joke shows, there is irony even in the void. Perhaps the quantum physicists are right and the unified field, the hypothetical basis of all existence, is smiling down on us.

Rabbi Isaac Luria once said that parents, in choosing the perfect name for their child, are temporarily bestowed with a gift of prophecy. Mystical tradition also holds that a name is not just a label, but a person’s very essence. I am called Simon, which means listening or hearing, and my name can be seen for the first time in Genesis 29:33 when Leah, meaning weary, says – because the LORD had heard that I was hated he had therefore given me this son whose name was Simeon.

Endnotes

1. A name that my grandmother used for other Jewish women in her neighbourhood. Schmendrick is Yiddish for a contemptible person.

2. Leader of the government in occupied Poland

3. Das, was geschah: that, which happened (Paul Celan)

4. Jewish townships that existed in Central and Eastern Europe before World War II

5. A system of matchmaking

6. Contraction (Hebrew)

7. Chaim Topol, Israeli comedian

8. Alta: old (Yiddish); Kaczki: ducks (Polish)

9. Remember (Hebrew)

10. Israel’s memorial to the victims of the Holocaust.

The essay won the 2022 Calibre Essay Prize. Calibre is worth a total of $7,500, of which the winner receives $5,000 and the runner-up $2,500. The Calibre Essay Prize was established in 2007 and is now one of the world’s leading prizes for a new non-fiction essay. The judges’ report is available on our website. ABR gratefully acknowledges the long-standing support of Patrons Peter McLennan and Mary-Ruth Sindrey.

Comments powered by CComment