- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Essay Collection

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: The heart of the matter

- Article Subtitle: Margaret Atwood’s athletic digressions

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Earlier this year, while still much occupied with our works in progress, Drusilla Modjeska and I discussed what our next projects might be. We were both tempted to put together a collection of our shorter writings – essays, talks, reviews, articles – already written and just needing a touch up. ‘Money for nothing and your books for free,’ I said, echoing the old Dire Straits song – albeit in a much more acceptable form for these sensitive times. And that’s the gift with collected writings: little work is required to produce a book. But a gift for the writer can be a risky business for the reader. After all, one cannot hope that all the disparate pieces (sixty-two in Margaret Atwood’s latest collection) will be equally as compelling as one Handmaid’s Tale.

- Article Hero Image (920px wide):

%20copy.jpg)

- Article Hero Image Caption: Margaret Atwood receiving the Franz Kafka Prize in Prague, Czech Republic, 2017 (CTK/Alamy)

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

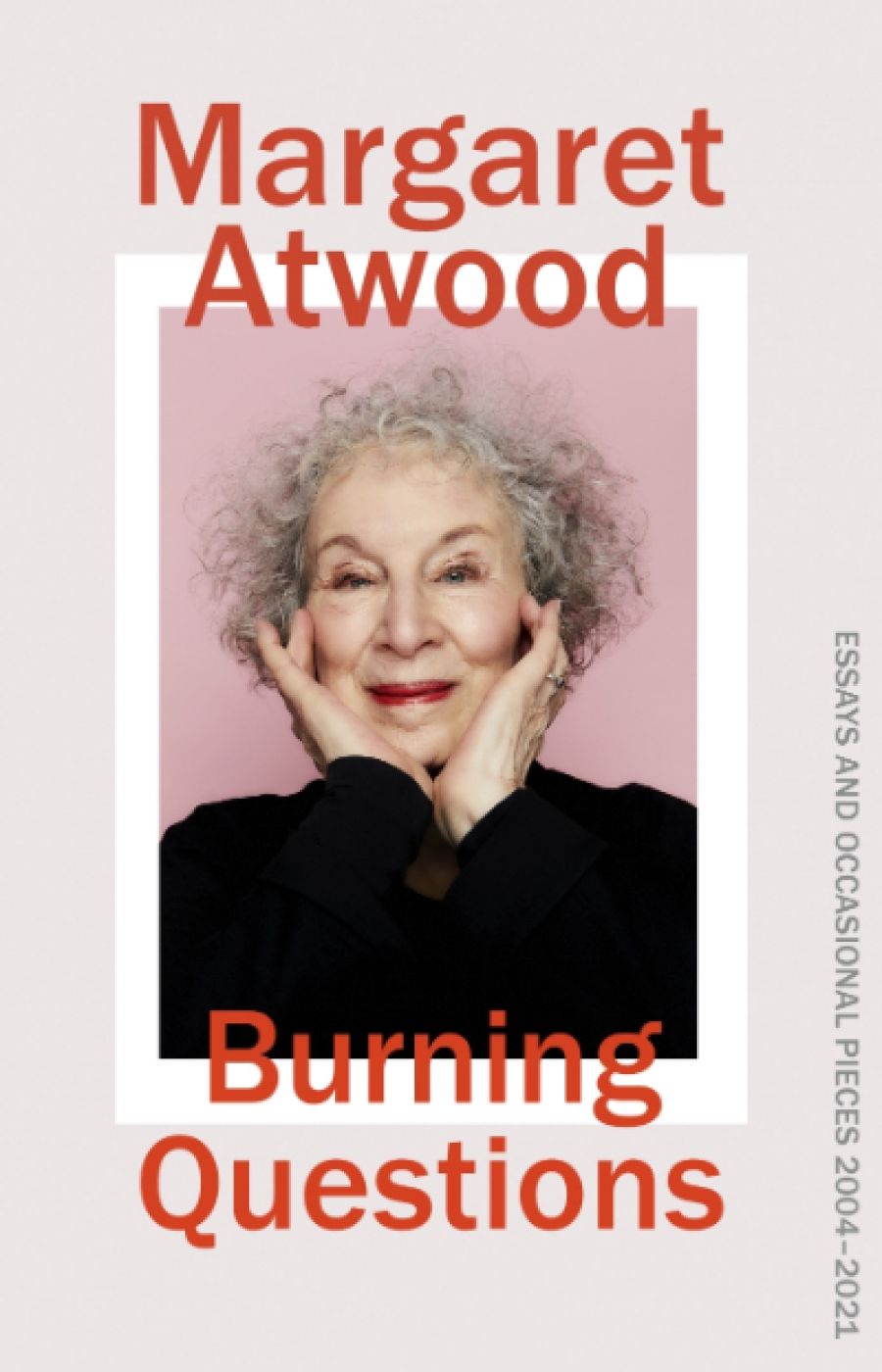

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Andrea Goldsmith reviews 'Burning Questions: Essays and occasional pieces, 2004–2021' by Margaret Atwood

- Book 1 Title: Burning Questions

- Book 1 Subtitle: Essays and occasional pieces, 2004–2021

- Book 1 Biblio: Chatto & Windus, $42.95 hb, 495 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/EaPagP

Most readers will come to a volume of collected writings as an established fan of the author: they’ve read the books, and now there’s more. The list of Atwood’s publications – novels, poetry, non-fiction, graphic novels, and children’s books – takes up two full pages of Burning Questions, and I have read a good many of them. But I know about collections: I know there will be slight pieces and forgettable pieces – and there are. But as an admirer of Atwood’s work, I also expect to find plenty that are punchy, original, and illuminating – and I do. (It was Somerset Maugham, well positioned to know, who observed that only the mediocre person is always at her best.)

Atwood’s first collection of essays and shorter pieces, Second Words, spanned 1960 to 1982, and her second volume, Moving Targets, took in 1983 to 2004. Burning Questions, covering the period 2004 to 2021, is divided chronologically into five parts, and the breadth of material is enormous. (Atwood is most definitely one of Archilochus’s foxes: she knows many, many things.) Yet certain themes recur: justice, human rights, moral agency, feminism, science and nature, and the reach and power of fiction.

There are speeches, launches, reviews, lectures, introductions to books (including a substantial introduction to her own Massey Lectures on debt), and articles for newspapers and journals. Some of the pieces are as short as two pages, others stretch to a few thousand words. There are so many talks, introductions, and articles: I cannot think of another writer so generous with her time and expertise. Maybe, given Atwood’s high profile, for every request accepted there are a dozen declined.

I began with one of her later articles, ‘What Art under Trump?’, written for The Nation in 2017, in which Atwood frames the question that has plagued so many of us in recent years: what happens ‘when reality exceeds even the wildest exaggerations of the imagination’? She advances a strong case for art – not simply for temporary respite in noxious times, but to illuminate and clarify seemingly incomprehensible beliefs and behaviours.

Beware leaders who bleed the arts.

Of the several introductions to books included in this collection, I particularly like her introduction to Simone de Beauvoir’s The Inseparables (2021). Atwood contends that Beauvoir ‘was, in a sense, haunted by herself’. Prompted by this haunting observation, I take my Beauvoirs down from my library shelf: I need to reread them. Atwood’s introduction to a new translation of Yevgeny Zamyatin’s novel We (1924) is another highlight. She situates this remarkable book within a discussion of other dystopian novels, Orwell’s in particular. I add my copy of We to the stack of Beauvoirs.

Her introduction to a new release of Dickens’s A Christmas Carol took me back to my library shelves, only to discover that I didn’t have a copy. Yet I know the story well – a point made by Atwood in this essay: how literary characters and stories become cultural tropes.

‘Reflections on The Handmaid’s Tale’ (2015) provides the background to the novel. It was not an immediate bestseller. Atwood wryly observes that it’s good to inherit a tough neck ‘if you’re going to stick your neck out’. I was fascinated by her lecture ‘The Writing of The Testaments’ (2020). She ranges across the rise of right-wing policies and the appeal of authoritarianism, as well as the collapse of totalitarian regimes. It was her particular interest in collaboration and collaborators that helped shape her decision to write a sequel thirty years after the publication of The Handmaid’s Tale. I read The Testaments as soon as it was released, and rather wished Atwood had not written it. But this essay has caused me to reconsider.

I add The Testaments to the pile.

Atwood’s wry humour and admirable bluntness appear liberally throughout this collection. In her 2004 review of Marilyn French’s three-volume history of women, From Eve to Dawn, she writes, ‘From Eve to Dawn is to Simone de Beauvoir’s The Second Sex as wolf is to poodle.’ And in ‘Shakespeare and Me’ (2015), about growing up in the 1950s: ‘In those days female poets were called poetesses, and girls took home economics and boys took shop, though both could take Latin.’ A couple of pages later, after a long quote from Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar: ‘Once caught in the riptide of iambic pentameter, it’s hard to stop.’

Atwood has often written about the natural environment. While two early pieces seem rather dated, another essay, ‘Literature and the Environment’ (2010), provides a lyrical journey into storytelling, the environment, and neural pathways, with a mention of narwhals, the most wondrous of living creatures.

Her essays on Ryszard Kapuściński’s The Emperor (2007) and on censorship (‘The Writer as Political Agent’, 2010) are gripping. ‘To judge novels on the justness of their causes or the “rightness” of their “politics” is to fall into the very same kind of thinking that leads to censorship.’ This is even more true today when identity politics is draining life from the literary imagination.

One expects points of disagreement in collections like these – it’s actually one of their pleasures. In her review of Richard Powers’ The Echo Maker (2006), Atwood speculates that The Wonderful Wizard of Oz provides ‘the underlying sketch’ for The Echo Maker. Perhaps she’s had a chat with Powers, but for my part I don’t see the connection, nor does it enhance the novel. With Atwood’s Sebald Lecture on translation (‘In Translationland’ [2014]), I was irritated with her many digressions (Atwood, with her prodigious knowledge, is an athletic digresser). But then, in the last third of the lecture, she settles in the main current, and hooks me in.

The collection begins with ‘Scientific Romancing’ (2004), a lecture on general fiction, science fiction, and the human imagination. Towards the end of the lecture, Atwood states that the arts ‘are not a frill. They are the heart of the matter ... A society without the arts … would no longer be what we now recognise as human.’

In Burning Questions, Atwood shows why art matters.

Comments powered by CComment