- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Literary Studies

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Pioneering legacy

- Article Subtitle: A poet’s love–fear relationship with the past

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Georgina Arnott’s 2016 biography The Unknown Judith Wright was an absorbing exercise in discovering the facets of Judith Wright’s early life and formative experience that were unknown, hidden, or forgotten, by biographers as well as by Wright herself. It was a revealing study of a writer who had a love-fear relationship with the projects of biography and autobiography. In the 1950s, Wright wrote loving, admiring histories of her pioneering family, but in her autobiography, Half a Lifetime, published in 1999, the year before her death, she began: ‘Autobiography is not what I want to write.’ There were good reasons for this. There were the formal challenges of life writing – the person writing is not the person written about – but also what Wright had discovered, in her archival research for her rewriting of her family history, about her Wyndham colonial ancestors’ role in Aboriginal dispossession, and violence.

- Article Hero Image (920px wide):

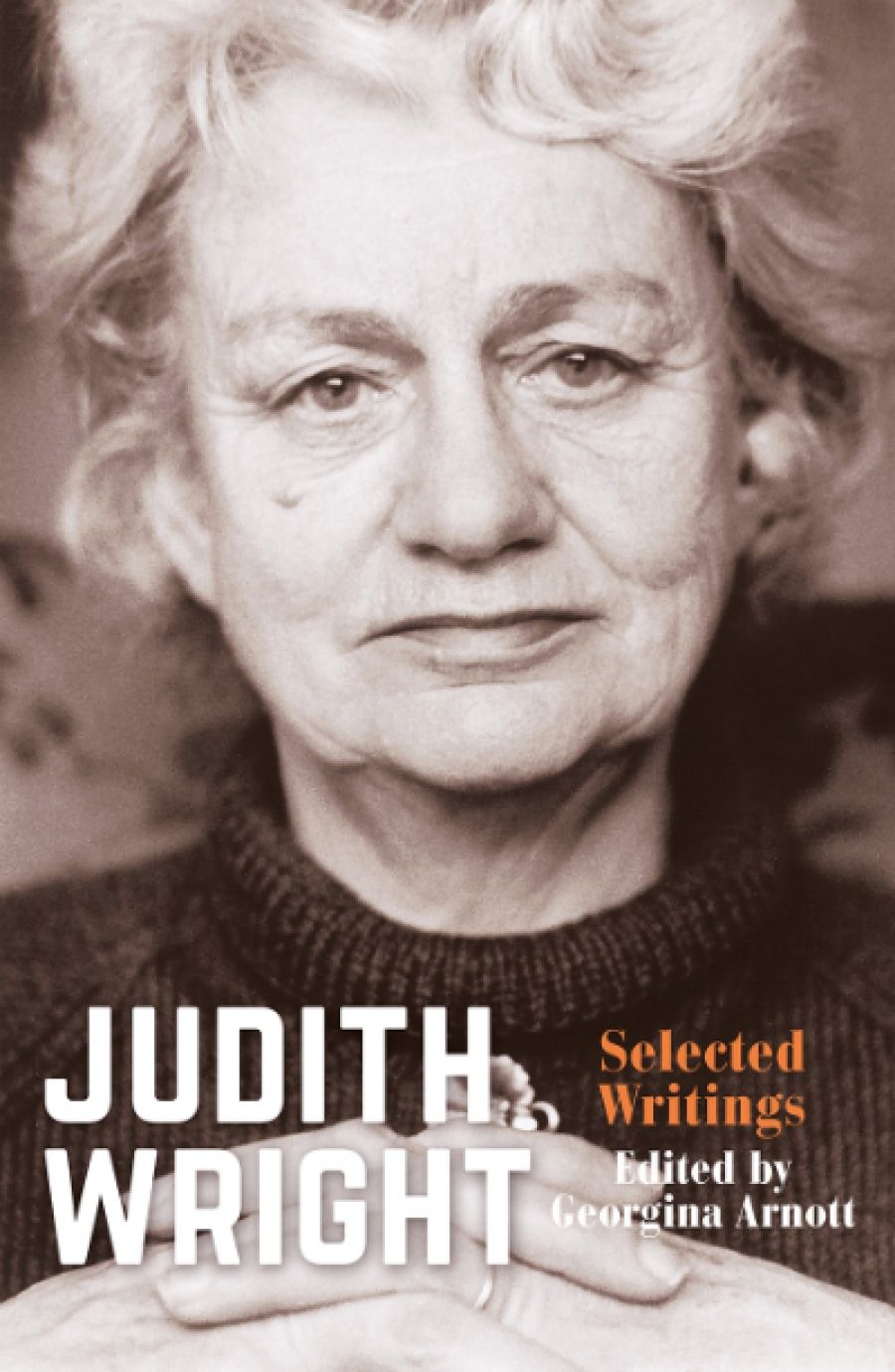

- Article Hero Image Caption: Portrait of Judith Wright, May 1998, by Terry Milligan (phra ajahn ekaggata FKA terry milligan/The National Library of Australia/PIC P2089 LOC Q97)

- Alt Tag (Article Hero Image): Portrait of Judith Wright, May 1998, by Terry Milligan (phra ajahn ekaggata FKA terry milligan/The National Library of Australia/PIC P2089 LOC Q97)

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Philip Mead reviews 'Judith Wright: Selected writings' edited by Georgina Arnott

- Book 1 Title: Judith Wright

- Book 1 Subtitle: Selected writings

- Book 1 Biblio: La Trobe University Press, $34.99 pb, 336 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/5bGbDj

Wright came to see she could never maintain a cordon sanitaire between her life and her writing, given that she wrote evolving family histories that were entwined in so many significant and duplicitous ways in the history (and historiography) of the nation. Poetry, of course, was different, but it also became contaminated, she felt, with misunderstandings about national history, the commemorative aspect of which she detested. As a protest against the Bicentennial, she forbade the inclusion of her poem ‘Bullocky’ in anthologies thenceforth. She felt readers and teachers misread her religious madman of a bullocky as a visionary celebrant of the pioneering enterprise.

Now Arnott has edited a first collection of Wright’s prose from across her writings in literary criticism, the environment and conservation, settler history, Indigenous activism, autobiography, and women’s issues. To complement Wright’s great achievements in poetry, this carefully curated collection presents her contributions to Australian public life and intellectual debates in the decades after World War II until her death at the turn of the millennium. The selection is certainly successful in one of Arnott’s aims as an editor: to ‘showcase the quality, range and dynamism of Wright’s non-fiction’. It’s good, for example, to be reminded here of the brilliance of Wright’s literary criticism. The 1955 essay ‘Australian Poetry: The English Poet in a Foreign Land’, originally a Commonwealth Literary Fund lecture, is a forceful expression of her understanding of poetry’s role as oppositional. Poetry, she writes, is ‘an assertion of values other than public values’. Poetry is about our inner lives, the ‘only truth about us’, and functions as reconciliatory dream-work between the individual and the historical, fallen world. In her insightful essay ‘Perspective’ (1948), Wright gets beyond the mere evaluation of the Jindyworobak poets’ work to the question of why the movement arose and what might be learned from it. The essay on John Shaw Neilson is still one of the most insightful readings of his work. As well as essays where she writes about the broader social understanding of poetry – poetry and universities, poetry anthologies, poetry in education – there is the important recognition of the ‘Koori Voice’. Her account of her time as a reader of poetry for Jacaranda Press in the 1960s and her support for the publication of Oodgeroo Noonuccal’s (then Kath Walker) manuscript of We Are Going (1964) is a crucial document in the advent of a new era in Australian literature. It’s a moment that fires her advocacy for Aboriginal writing in the face of considerable prejudice from the literary and academic establishment.

Of interest to some readers will be Wright’s 1965 essay ‘Art and National Identity’. This was in response to Sibnarayan Ray and Achdiat K. Mihardja’s article in Hemisphere magazine where they accused Australia of a failure to discover its own creative personality. Wright’s response was an argument about the deep quarrels between the artist and society, and the unresolved realities of white settlement and the idea of a free and creative community. What is also interesting about the essay is how Wright thinks about the accusation that Australia has neglected to ‘find our way outwards to our Asian neighbours’.

The writings about the many ways in which Wright thought about the human relation to nature and environmental activism are important for their expression of a specifically Australian ecological consciousness and for historical reasons. Wright was an impressively knowledgeable writer about the philosophical, economic, and political aspects of environmental thinking, always insisting on the relevance of the arts and the imagination to such thought.

Also included in Arnott’s selection are Wright’s writing about the specific and local perspectives on these issues, as in the 1970 essay ‘Trees and Australians’, which begins with the admission that four generations of Wright’s forebears ‘spent a lot of their time battling against Australian trees’. Her understanding (and critique) of the first, pastoral wave of white settlement in Australia has the authority of this kind of historical depth. These writings are also important for their account of Wright’s involvement in the history of organised nature conservation in Australia, her co-founding of the Wildlife Preservation Society of Queensland, her work as a founding member of the Australian Conservation Foundation, and as a member of the Whitlam government’s Heritage Commission. Included here is Wright’s introduction to The Coral Battleground, her 1977 book about one of the earliest campaigns she was involved in.

Wright’s activism from the 1970s for Indigenous causes is intimately related to her environmentalist work. In a small column from the Aboriginal Treaty News of 1983, where she gives an account of her part in the Aboriginal Treaty Committee, she answers critics who ask why a writer ‘should neglect the “duty” of writing in order to get involved with political questions and moral engagements such as those with conservation and Aboriginal rights’. For Wright, ‘writing, and what you write are never neutral factors. What you choose to become involved with or to ignore is a political choice – not party political but an active expression of yourself.’ In the nearly quarter century since Wright’s death, there is a sense of achievement and hope about the Indigenous issues that Wright contributed to, whatever the setbacks and challenges that remain. But reading Wright on the environment and conservation, it’s hard not to feel sad. So much of her effort in humanist discourse about the importance of nature conservation, and so much of her political work in environmental causes, have been swamped by the emergencies of climate change and the contested politics of global warming. In The Coral Battleground, the threat was a local one; now it is global.

All these writings belong to the story of someone who knew she was going to be a poet from a young age, but whose mind also developed and changed through its engagements with social and historical streams in Australian life. Alongside the linguistic and aesthetic dramas of her poetic trajectory, there is the powerful revisioning of settler history centred on the rewriting of The Generations of Men (1959) in the Cry for the Dead (1981), and Born of the Conquerors (1991). This revision in personal and national narratives is signalled in an essay in Hemisphere magazine in 1963, ‘What It Means to Be a Descendant of Pioneers’. There is a reminder here of Wright’s deep personal investments in this story in the excerpts from The Generations of Men, with their sumptuous writing about her paternal grandmother, May. In the much less fictionalised rewriting of this family history in The Cry for the Dead, informed by decades of archival research, Wright tries as much as she can to repopulate the story with the Aboriginal people of the Hunter, New England, and Burnett regions, where her family were pastoral settlers. It’s a melancholy project, though, given what she has learnt about the murderous, exploitative history of the settler invasion and her ancestors’ role in that history.

For all the skill and empathy of this collection, there’s something missing. Arnott does mention the intellectual collaboration between Wright and her partner Jack McKinney in her introduction, but only very briefly. This collection doesn’t include any of their letters or other writing by Wright that illustrates the long, mutually formative role of their collaboration. One has to go to Patricia Clarke and Meredith McKinney’s selection of Wright’s and McKinney’s letters from the early years of their relationship – The Equal Heart and Mind (2004) – for that important part of Wright’s life story. The whole intellectual climate of The Moving Image (1946), Wright’s first book of poetry, with its Platonic title, is imbued with the contemporary sense, that Wright shared with McKinney, of a crisis in Western thought and civilisation. As a non-professional philosopher, McKinney published two books, The Challenge of Reason (1950) and The Structure of Modern Thought (1971), both of which Wright helped him to write and to publish. And one of McKinney’s strongest themes was that ‘knowledge is an interpersonal thing’.

Comments powered by CComment