- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Dancing on air

- Article Subtitle: The bunglings of Nosey Bob

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

When the offer came to review this book, I accepted enthusiastically, and unthinkingly added, ‘That sounds fun!’. Upon reflection, I deleted that last sentence: what would it say about me, I wondered, that I should expect the account of a hangman and his work to be entertaining? I thought better of the sentence, but the anticipation remained.

- Article Hero Image (920px wide):

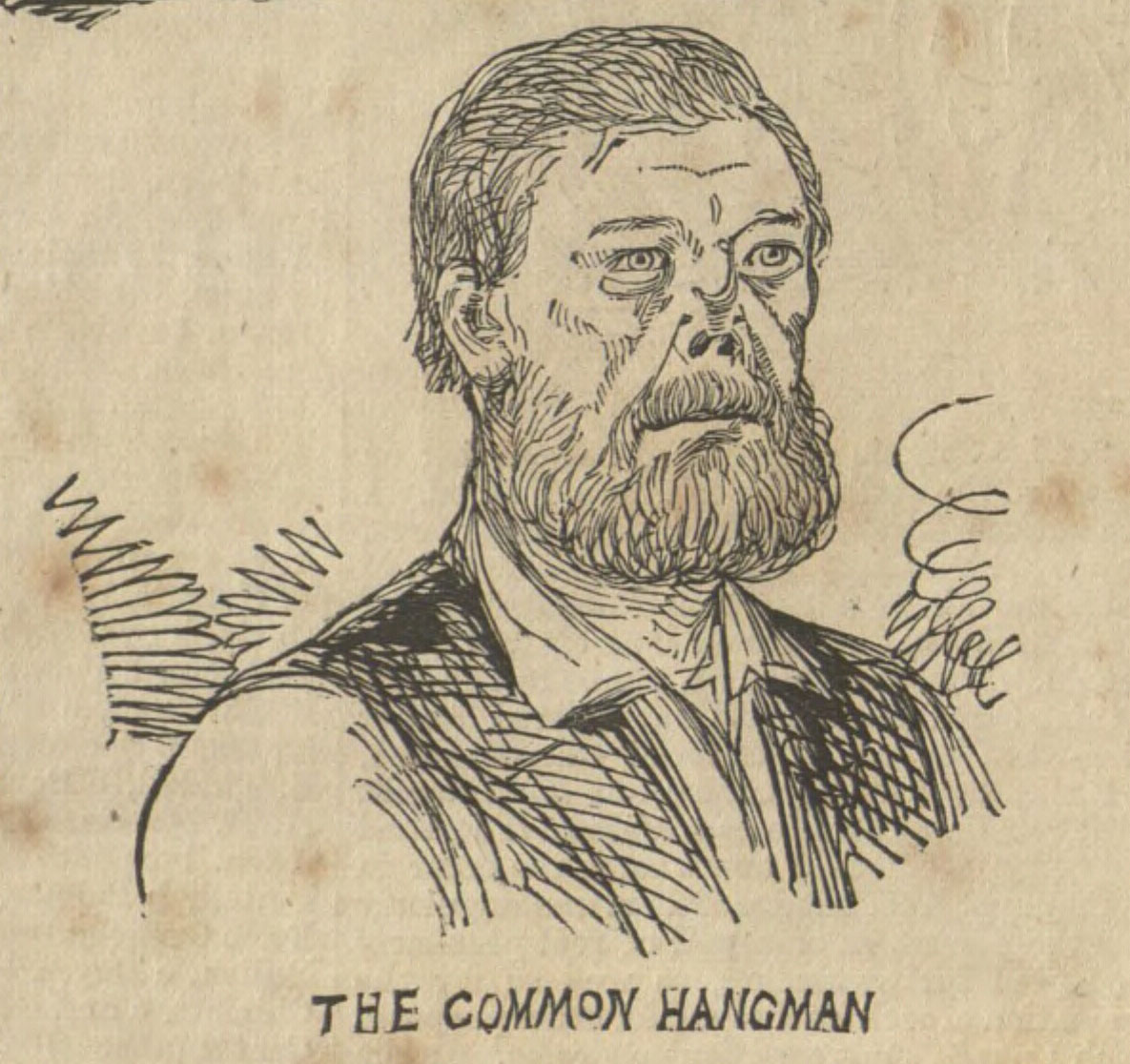

- Article Hero Image Caption: An illustration of Robert "Nosey Bob" Howard in <em>The Bulletin</em>, 31 January 1880, p4 (National Library of Australia/Trove)

- Alt Tag (Article Hero Image): An illustration of Robert "Nosey Bob" Howard in The Bulletin, 31 January 1880, p4 (National Library of Australia/Trove)

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Penny Russell reviews 'An Uncommon Hangman: The life and deaths of Robert "Nosey Bob" Howard' by Rachel Franks

- Book 1 Title: An Uncommon Hangman

- Book 1 Subtitle: The life and deaths of Robert "Nosey Bob" Howard

- Book 1 Biblio: NewSouth, $34.99 pb, 417 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/MXVXY3

Playing to the popular appeal of the macabre, the book and its packaging invite such pleasurable anticipation. The cartoon sketch of Robert Howard on the cover, the use of his moniker, ‘Nosey Bob’ (a very Australian reference to the fact that he had mysteriously lost his nose), and the review-style endorsements that justly spruik the wit and warmth, light touch, and gallows humour of Rachel Franks’s narrative, all encourage it. But (as the endorsements also acknowledge), for all her lightness of touch, Franks never allows us to forget the intimate brutality of the act of hanging. No one, I quickly realised, should turn to this book in search of light entertainment.

‘Nosey Bob’ was responsible for the deaths of sixty-one men and one woman in New South Wales between 1876 and 1903. Forty-six of these were clean deaths: the neck was broken by the impact of the drop, and death followed instantaneously. Four more deaths were instant but gruesome, the head almost – or, in one hideous case, wholly – severed from the body. In the remaining twelve, either through some miscalculation of the rope or the drop, or through bungled execution (variously attributed to a crowded platform, a struggling ‘patient’, or an inexperienced assistant), the neck was not broken, and unfortunate men and boys were strangled to death, sometimes with horrifying slowness. Franks argues that taking his career as a whole Nosey Bob’s success rate was quite impressive, but those dreadful strangulations did his reputation no good. They fuelled arguments for the abolition of capital punishment, but also criticism of his errors of judgement and calls for his replacement.

Franks tells the life story of Robert Howard in the only way it can be told: through his many executions. These are interleaved with detail, skilfully recovered, of his life as a family man, a peaceable resident of Paddington and later of Bondi, a cabby before he turned executioner, a gardener, a humorist. But inevitably, death dominates the book. Each hanging is described in almost excruciating detail, at once clinical and humane. There are Nosey Bob’s executions, but others as well, including a painfully empathetic account of the first hanging ordered in the colony in 1788. Weaving backwards and forwards through time, Franks builds a strangely fascinating picture of capital punishment in a white settler society. Each hanging story follows the same inexorable arc, from the crime (itself often gruesome enough), through the trial and sentencing to the placing of the noose, the drop, and the death. Fast or slow. Clean or bloody. For good or ill, the horror of each moment is dulled by the pace at which we move on to the next.

Versed in the genres of true crime and crime fiction, Franks does much to make the macabre more palatable. Her humour infuses the book. The simple device of framing Howard’s occupation as the civil service job it was – with deadpan talk of career changes, references and reviews, workplace health and safety – provides a down-to-earth, often humorous, check on horror. So too does her adoption of the voice of a hard-boiled crime-writer, aided by free use of the contemporary vocabulary of execution. A glossary at the front of the book lists the startling variety of euphemisms for being hanged (cast off, operated on, seen off, sent into eternity, turned off, dancing on air) and the unfortunate ‘executee’ (condemned, culprit, client, patient, victim of the law). Her lexicon established, Franks sprinkles these terms through her book without recourse to apologetic quotation marks. Euphemism serves here, as it did for contemporaries, to build a nonchalant, ironic detachment from the intimate act of killing.

Overt gallows humour also leavens the grim account. Some of the best examples come (allegedly) from Nosey Bob himself. Helping the frail King’s Counsel into his overcoat, he murmurs appraisingly ‘You’ve got a bee-utiful thin neck, Mr. Blacket.’ Blocked from entering a crowded tram, he fires a Parthian shot at the seated passengers: ‘Perhaps you’ll have to stand yourself one day!’

No amount of gallows humour can make the story of sixty-two violent deaths an enjoyable read. And Franks discourages ghoulish relish, guarding her subject from voyeuristic sensationalism by never allowing us to forget the humanity, either of Nosey Bob or of his clients. At the heart of her book lies a sad story: of a life soured by accident or illness (Franks offers several possible explanations for Howard’s notorious noselessness) and of a man compelled to take on a difficult job that no amount of practice or expertise could make less painful. ‘My poor man (or woman), no one regrets this more than I do,’ said Howard to each of his patients in turn. You cannot doubt that he meant it.

Notwithstanding Franks’s impressively forensic research, little is known of Howard beyond his role as a dealer of death. Yet his life gives this picaresque, sprawling book its narrative thread and emotional heart, drawing the reader into some curiously divided sympathies. We are insistently reminded that he was just a man doing an unpleasant task, carrying out a cruel sentence he had no part in ordering, shunned and reviled by a society that nonetheless largely condoned this brutal punishment. As she weaves Howard’s story into a larger account of growing opposition to the death penalty and moves towards its abolition, Franks invites reflection on our colonial past and its complex legacies of morality and justice.

Comments powered by CComment