- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Australian History

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: A din of competing noise

- Article Subtitle: Confronting history at Tennant Creek

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

In Telling Tennant’s Story, Dean Ashenden gives a lucid, succinct, eminently readable account of the reasons why Australia as a nation continues to struggle with how to acknowledge and move beyond its past. Travelling north to visit Tennant Creek for the first time since leaving it as a boy in 1955, Ashenden is provoked to question the absence of shared histories on the monuments and tourist information boards along the route. Mostly, the signs record pioneer history, from which the Indigenous people are absent. When the Indigenous story is invoked, it records traditional practices and does not mention white people. ‘How did they get from then to now?’ he muses. ‘Just don’t mention the war.’

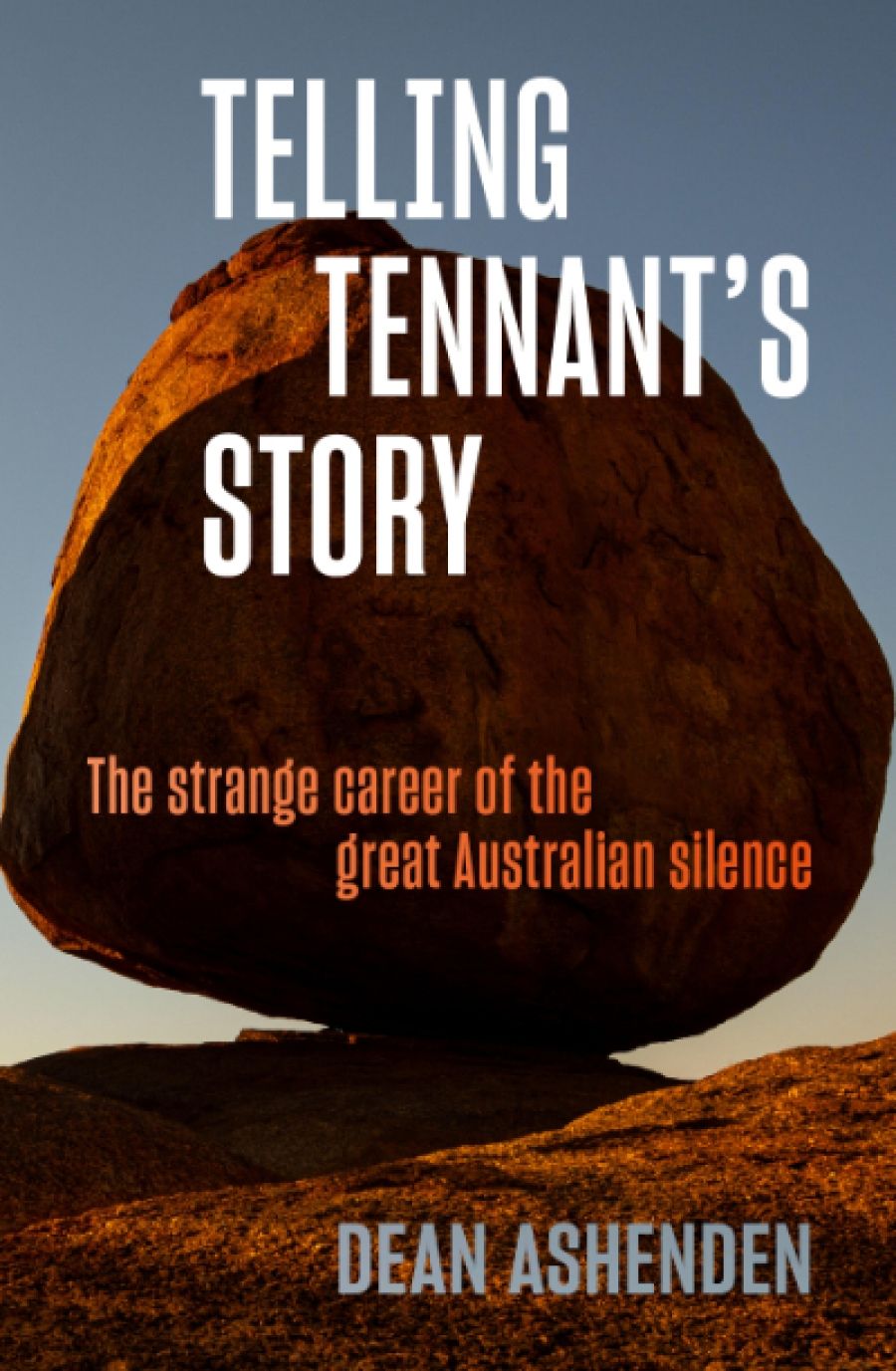

- Article Hero Image (920px wide):

- Article Hero Image Caption: Karlu Karlu (Devils Marbles) at dawn, near Tennant's Creek (Ingo Oeland/Alamy)

- Alt Tag (Article Hero Image): Karlu Karlu (Devils Marbles) at dawn, near Tennant's Creek (Ingo Oeland/Alamy)

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Kim Mahood reviews 'Telling Tennant’s Story: The strange career of the great Australian silence' by Dean Ashenden

- Book 1 Title: Telling Tennant’s Story

- Book 1 Subtitle: The strange career of the great Australian silence

- Book 1 Biblio: Black Inc., $34.99 pb, 352 pp

Bookending the narrative are Ashenden’s experiences, first as a boy living in Tennant Creek in the early 1950s when his father was headmaster of the local school, and later as a man returning more than fifty years later, compelled by the persistence of the historical silence to explore the contradictions of its legacy. ‘By the time I’d made the last of three trips back to Tennant I’d learned that the struggles over whether and how to tell Tennant’s story were for a century and a half Australia’s struggles writ small, and intense.’

Moving between anthropology and history, public policy and political activism, to detailing the particularities of Tennant Creek and its Warumungu and Anglo-Australian inhabitants, Ashenden illustrates the influence of those disciplines on the lives of individuals living in and around the town. He examines the insights and oversights of anthropology, from Spencer and Gillen through Elkin to Stanner, after which the baton is passed to history, and the evolution of the parallel narratives exemplified by Geoffrey Blainey and Henry Reynolds.

Any book that mentions the great Australian silence in its subtitle signals the guiding presence of W.E.H. Stanner (1905–81), the anthropologist who coined the term and set about attempting to break the silence. Stanner’s anthropological career had its beginnings in Tennant Creek in 1933, in the early days of the gold rush in which the town itself had its beginnings, graduating from its origins as a telegraph station and later becoming a ration depot. The surrounding country had already been taken up by pastoralists, and the local Warumungu people had made various accommodations with the options available to them, the best being work on the stations and the worst as fringe dwellers around the mining camps. Stanner noted the threats posed to the Warumungu by the expansion of the town and the mines, and reported his observations to the government, after which he embarked on his ground-breaking fieldwork further north. It was another twenty years before he began to formulate the intellectual vision that provided his foundational argument against assimilation, based on his recognition that ‘the Aboriginal and the European ways of being in the world are fundamentally different’.

Ashenden gives a fascinating account of the parallels between Stanner and his political counterpart Paul Hasluck (1905–93), who was a committed proponent of assimilation. Exact contemporaries with similar social and educational backgrounds, powerful intellects, and forceful personalities, the two men reflect the opposing strands of thought that influenced policy and practice with repercussions that resonate today.

Hasluck’s assimilationist orthodoxy contained the assumption that the Aboriginal people were ‘citizens in waiting’, who would, through structural change and the compassionate and responsible policies of assimilation, be brought into equal citizenship with other Australians. Embedded in the policy structure and the influential urban intellectual class was the notion that Aboriginal people were white people with black skins, and that the barriers to equality were grounded in the visual differences and associated prejudices of skin colour. Stanner saw what Elkin, Hasluck, and others failed to see – that the difference went much deeper than skin, and was constructed by a profound and complex relationship in which every part of the land and its human occupants was connected through belief, ritual, and kinship. He predicted the persistence of difference through all the attempts to eradicate it. In Telling Tennant’s Story, Ashenden examines how the persistence of both the difference and the attempts to eradicate it have manifested in Tennant Creek and, by extrapolation, in Australia.

Reading this book provided me with a context and a scaffolding for much that has influenced my own thinking over the past decades. Teasing out the changes that occurred after the 1967 referendum, Ashenden flags the perfect storm created by the ushering in, more or less simultaneously, of equal pay, welfare payments, and drinking rights. The failure of policies driven by good intentions and poor understanding sets a pattern that seems entrenched in governments of all political persuasions. By the time Aboriginal voices found their way into the conversation, the fault lines were deeply etched into both the practical and psychological processes of race relations in Australia.

In 1938 Stanner wrote, in response to the government’s ‘new deal for Aborigines’:

Here are high official aspirations, unimpeachable liberal social principles, an ambitious paper plan, an objective dimly conceived and pleasantly worded. Here, apparently, is belief that prejudiced men, case-hardened viewpoints, vested interests, a bureaucracy with a long tenure of office yet to run, and a proven difficult environment will belie their history and become conveniently malleable … Policy is put into operation with its head in a whirl, accompanied by the hope that things will sort themselves out … This is where the defensive official myths start, and this is also why it is so hard for both officials and public to see where truth lies.

In more than eighty years, it is alarming to see how little has changed. Although Stanner’s voice has prevailed through time, he was ignored when it mattered. As Ashenden observes, the great Australian silence was not so much a silence as a din of competing noise to drown the voices that challenged the official orthodoxies.

In this mediated journey through the ideas, convictions, and decision making of Anglo-Australian men, and its impact on the lives of Aboriginal people, Dean Ashenden pools his skills as a journalist, his passion for a truthful ground on which to converse, and the subterranean influences of childhood memory, to create a compelling, beautifully written, and essential contribution to the project of constructing a culture that makes room for all of us.

Comments powered by CComment