- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Animal Rights

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Animal trials

- Article Subtitle: Exploring the human desire for retribution

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

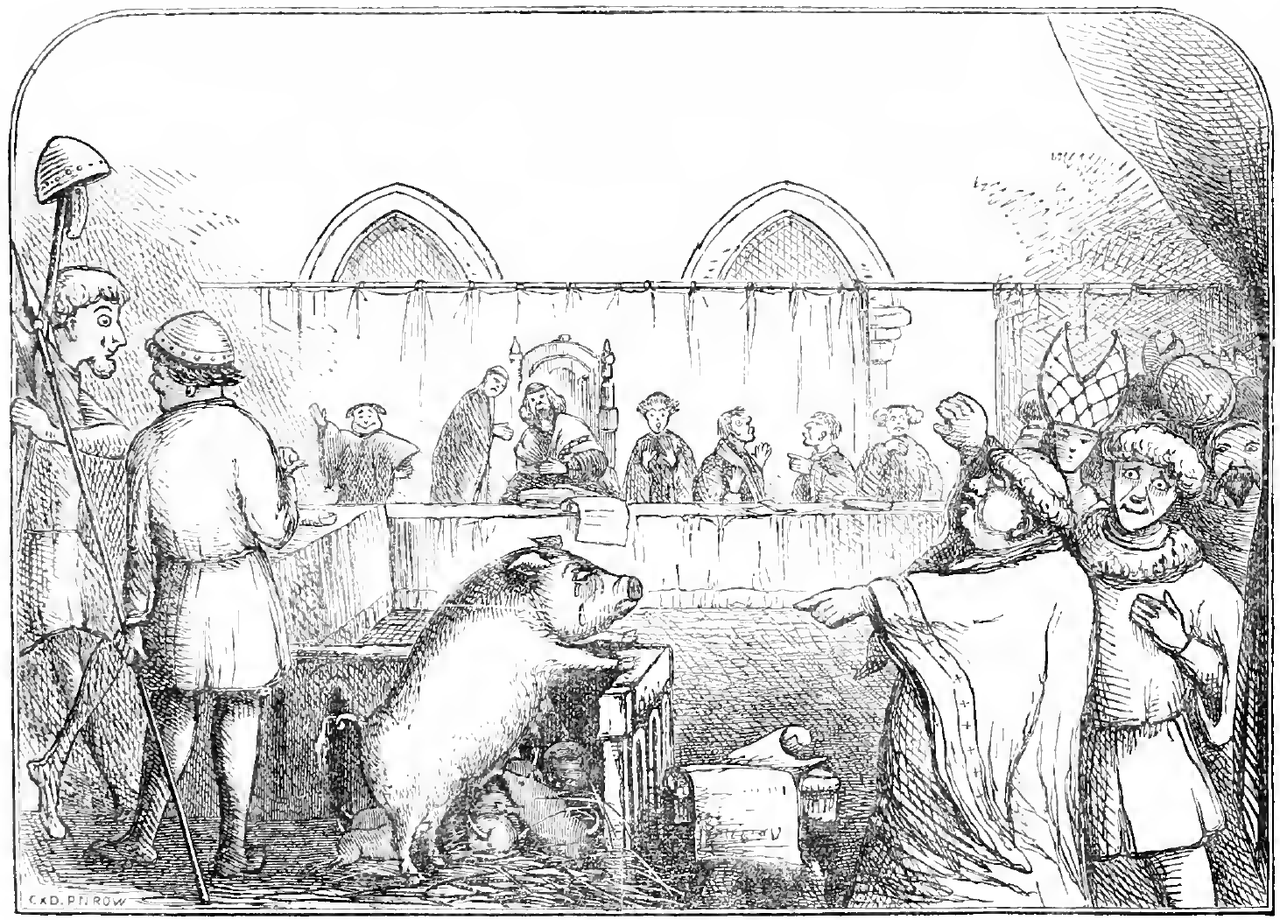

The title of this book, Guilty Pigs, is a reference to the medieval practice of bringing animals and insects to trial and/or punishing them for their conduct, such as killing humans, or destroying orchards, crops, and vineyards, or, in one case, chewing the records of ecclesiastical proceedings. The behaviour of the animal or insect determined whether proceedings were brought in secular or ecclesiastical jurisdictions. A charge of homicide would be initiated in secular tribunals, where domesticated animals such as pigs, cows, and horses were tried and punished, invariably by pronouncement of the death penalty. When animals and insects such as rats, mice, locusts, and weevils invaded houses, fields, or orchards, proceedings were brought in ecclesiastical courts, which eschewed the death penalty, instead excommunicating the hapless defendant.

- Article Hero Image (920px wide):

- Article Hero Image Caption: Trial of a sow and pigs at Lavegny in 1457 from <em>The Book of Days</em> (1869) by Robert Chambers (Wikimedia Commons)

- Alt Tag (Article Hero Image): Trial of a sow and pigs at Lavegny in 1457 from The Book of Days (1869) by Robert Chambers (Wikimedia Commons)

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Sophie Riley reviews 'Guilty Pigs: The weird and wonderful history of animal law' by Katy Barnett and Jeremy Gans

- Book 1 Title: Guilty Pigs

- Book 1 Subtitle: The weird and wonderful history of animal law

- Book 1 Biblio: La Trobe University Press, $34.99 pb, 355 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/x9v9od

At first glance, these trials might appear to be nothing more than amusing anomalies, footnotes to the history of criminal justice systems throughout western Europe. Katy Barnett and Jeremy Gans, however, cite these cases, as well as others occurring from the Middle Ages to the present, to construct a rich narrative of human–animal relations. In doing so, they convincingly argue that, in its various guises, what is termed animal law ‘is really just a particular application of human law’. This observation makes the medieval animal trials all the more intriguing because, from at least the time of St Thomas Aquinas (1225–74), society accepted that animals lacked the type of cognitive abilities ascribed to humans. Accordingly, animals were not considered rational, which justified their exclusion from the hypothetical social contract that allowed humans to accept social benefits in return for shouldering social obligations. What is more, by the eighteenth century, Enlightenment philosophers such as David Hume (1711–76) reinforced the argument that animals’ inferior cognitive abilities excluded them from the ‘realm of justice’. At the same time, this line of thought did little to explain the animal trials, which, in the case of murder, required evidence of intent, and by extension evidence of cognitive abilities, akin to those attributed to humans.

Barnett and Gans point out that the animal trials may be explained on a number of levels that do not necessarily hinge on animals’ cognitive abilities: upholding the law as ritual; preserving public safety by deterring crime; as well as providing a means of retribution. With respect to the latter, the trials demonstrate how retribution could occur within the parameters of the law, although the authors also detail cases, up to the twentieth century, of animals being killed extrajudicially for harming humans and other animals.

One such case involved the lynching, in 1916, of an elephant named ‘Mary’ for killing her trainer. Although Mary, in common with other animals, could not be accused of moral culpability or legal intent, the human compulsion to exact retribution against what appear to be ‘intelligent killer animals’ weaves its way throughout the history of human–animal relationships. The authors provide numerous other examples, including shark culls and the hunting down of dogs, wolves, and even kangaroos.

In the centuries after the Middle Ages, the law’s focus shifted from trying animals directly as defendants to imposing liability on owners, or those in control of animals. Nonetheless, as in the animal trials, animals could still receive the death penalty because authorities retain the power to order the destruction of aggressive or dangerous animals.

The book commences in 2012 with just such a tale: that of Izzy, a four-year-old Staffordshire terrier, whom Knox City Council, in Victoria, had classified as dangerous. The council ordered Izzy to be euthanised because she had attacked a Jack Russell terrier and a border collie and also injured a woman who had tried to stop the attack. The book returns to this story several times, juxtaposing Izzy’s tale against the progress of the law, questioning whether, in reality, much has changed in the way society makes animals pay for their ‘crimes’.

Outside the criminal law, attempts by humans to care for animals have led to unusual developments in the fields of probate and family law. In Western jurisdictions, testamentary dispositions cannot be made directly to animals, but courts have long upheld trusts for the maintenance of animals upon their owner’s death, tacitly accepting that animals are more than inanimate property. This line of reasoning, however, has not filtered through to family law jurisdictions, where disputes about companion animals are becoming increasingly common following relationship breakdowns. In Australia, courts treat companion animals as if they were any other property, so that it is not possible to apply for custody orders, as occurs with children. In the United States of America, however, some jurisdictions can indeed make custody orders, by considering what is in the best interests of the companion animal. These developments demonstrate that rules can evolve, giving legal expression to social changes. In particular, while anti-cruelty regulation has existed from at least the early part of the nineteenth century, the law recognises that, at least for some animals, a higher standard of protection is appropriate.

The authors’ backgrounds in private law, comparative law, criminal law, animal law, and legal history guarantee a breadth of legal knowledge that is clearly visible in the way they integrate and explain complex issues, making them easy to understand. They incorporate a wide range of material from the private and public law areas, including property law, probate, criminal law, torts, and Roman law. The book – erudite, informative, entertaining – takes the reader on a journey from antiquity to the present. At the same time, it does not lose sight of an important underlying question regarding how legal regimes should respond to shifting social values, which increasingly view animals as sentient individuals with interests that matter to them as much as human interests matter to humans. This is reflected in the observation by the authors that courts waver between treating animals as inanimate property and regarding them ‘as living beings with agency and needs of their own’. The material is written in an approachable style and will appeal to a wide range of readers, extending beyond the obvious market of lawyers and animal advocates.

Comments powered by CComment