- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Poetry

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Living difference

- Article Subtitle: The poetics of knowledge and territory

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

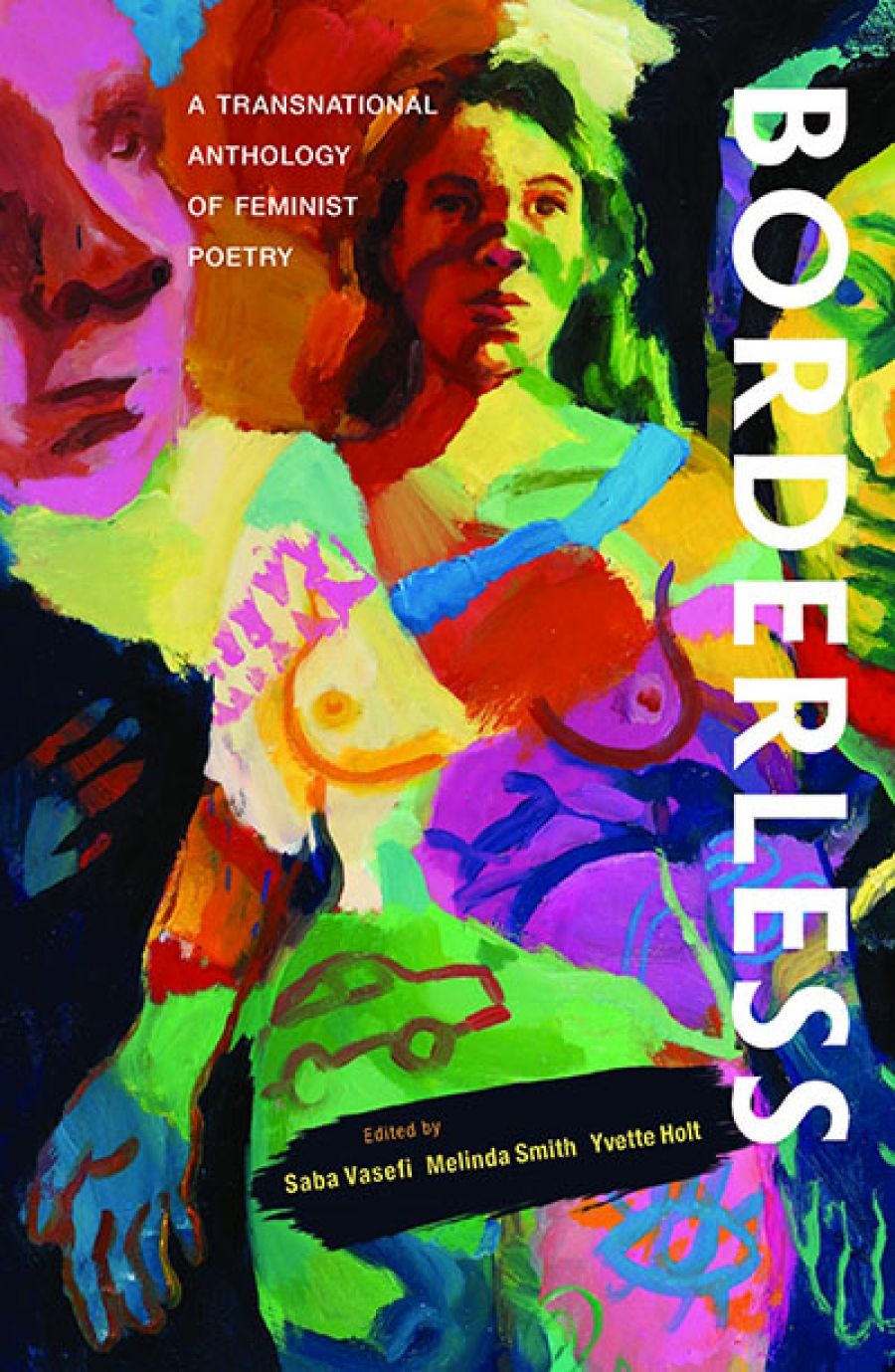

‘Borderless’ is ‘a transnational anthology of feminist poetry’, arranged alphabetically with no themed sections, that I read slowly, out of paginated order, and savoured. Is ‘Borderless’ a description or an ideal? I wondered, as I returned, between poems, to look at the cover image of a multi-coloured painted woman, a body located in no place I could discern. Does ‘Borderless’ refer to a poet’s ability to dissolve borders through imagination, or to a temporary state of flight or transgression? Perhaps, a borderless world is one akin to a poetry anthology with no hierarchy or divisions to order the poems and their meanings.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Nadia Rhook reviews ‘Borderless: A transnational anthology of feminist poetry’ edited by Saba Vasefi, Melinda Smith, and Yvette Holt

- Book 1 Title: Borderless

- Book 1 Subtitle: A transnational anthology of feminist poetry

- Book 1 Biblio: Recent Work Press, $24.95 pb, 240 pp

A thread holding this unusual collection together is the way that poems are formed through and against forces of oppression. Chief editor Saba Vasefi reflects in her introduction: ‘These poems carry with them the ancestral journey of marginalised storytelling which has survived and thrived throughout the checkered season of colonialism and patriarchy.’ Is what characterises a feminist poem the use of story not only to carry knowledge, but to claim it? I know how oppression works, so many of these poems said to me.

Sista Zai Zanda’s ‘A Poem In Honour Of A Lioness Perfecting Her Balance of Inner/Outer Power’ knows ‘Gentleness’ to be the Lioness’s ‘superpower’. Eleanor Jackson’s ‘nominated intimacy’ knows that the hegemonic cast of the marriage contract means one can find oneself obeying something one knows to be a patriarchal construct. Jennifer Maiden’s poem ‘Diary Poem: Uses of Iron Ladies’ knows that the presence of a woman in a place of power – namely, Margaret Thatcher – doesn’t equate to women’s liberation, and might even work to entrench gender inequity. Melissa Lucashenko’s poem ‘Screaming Blue Murder’ knows about the murder of a Filipino woman by a Queensland policeman. Her use of collective pronouns foresees the reader wanting to turn away from the horror, and suggests that complicity begins in turning away.

If there is strength to be found in knowing that the effects of patriarchy are as grim as death, it is in the release that such knowledge offers. ‘She’ll die as another madwoman in the attic / Trapped in sedation’, Cassandra Atherton writes in ‘Single pink slipper’. The last line rejects victimhood, claiming ownership of a life driven ‘mad’.

Lost in silence.

None of it is yours.

In her unflinchingly honest poem ‘optimal’, Gomeroi poet Alison Whittaker knows her body’s dignity despite and through the pernicious indignities of racialisation. She also knows the gaslighting that occurs when someone takes a photograph of your body but pretends they didn’t.

After weight loss surgery, Whittaker writes:

… another

fat girl takes my photo! Does she know that I

know that she knows that I know? Do I know

that she knows? No.

Knowledge is here a complex relational game played amid the pernicious effects of patriarchal colonialism.

This collection might be seen as ‘diverse’ in the neoliberal sense that these writers identify with an array of sexualities, ethnicities, and nationalities. The differences that live between these poems, however, are deeper and more significant than the shorthand labels often deployed to denote ‘diversity’ in the neoliberal order. It seemed as if each poem in this collection lives within what feminist historian of race relations Samia Khatun has called a ‘knowledge relation’; here, a relation between poet and experience, between experience and history, between history and feminist cultures and ideologies. If colonial knowledge seeks to dissect the world scientifically, poetry proves to be an affective space in which to make it whole again. This is why I was eventually grateful for the collection’s alphabetical arrangement. There was no social or moral logic to the order in which I met each poet, no familiar identity categories or categorisations that risk flattening out difference. As such, the collection compelled me to practice dropping my expectations and instead meet each poem, the language of each knowledge relation, on its own terms, and to listen to each poem as a world abundant in itself.

As Vasefi’s introduction suggests, not all women have been equally oppressed in the lumpy histories of imperialism. In ‘On International Women’s Day’, Wiradjuri writer and academic Jeanine Leane playfully addresses her imposed sameness with White women, drawing a parallel between the absurdity of abstracting her identity from her embodied reality, and the liberatory aspirations of white feminism.

You’re just like us

The white women at my work tell me when I

Decline their invitation to celebrate ...

My skin is blak. Inside is my womanhood

Do I peel my skin from my body or wrench my body from my skin?

Either way feminism will make me bleed

Numerous First Nations poets share knowledge about the gendered workings of colonialism. I was drawn to these lucid poems. For Wirlomin-Noongar writer and poet Claire G. Coleman and Nyikina Warrwa academic Anne Poelina Wagaba, liberation comes through a relationality beyond an anthropocentric maternal ‘matrix’. In Poelina Wagaba’s poem, ‘First Law: Matrix or Patrix’:

Birds, fish, insects, flowers, bush bees, snakes and lizards with others amongst the grass.

Sameness in value of life between human and non-human beings

Not Matrix deconstructing Patrix

First Law, Law of the Land

These poems, as Vasefi writes, work to ‘reterritorialize’ space, and they do so in internal as much as in outward ways.

In ‘A love like that’, Pakistani-Australian writer Zainab Z. Syed reckons with her indebtedness to her ancestors: They

… did not cross the border

for me to carry shards in my chest

At the poem’s end, we discover that it’s only after entering a relationship in which one is not only able to speak, but also able to be understood, that an emancipatory love will flourish.

‘O my Lord, expand for me my breast … and untie the knot

from my tongue that they may understand my speech.’ (Quran, 20:25-28)

and then watch, what happens to a love like that!

A concerted labour of co-operation on the part of Saba Vasefi, Melinda Smith, and Yvette Holt has brought together a chorus of cerebral poems that lead me to ask: where is my feminism? What should be its territory?

Comments powered by CComment