- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: French Studies

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Those wanting to understand better the radical changes in Western thought and social mores since World War II could benefit from revisiting Jean-Paul Sartre (1905–80). Of course, one can sympathise with Jonathan Rée in his critique of much of Sartre’s work as ‘slap-dash’, ‘long-winded’, ‘carelessly profuse’ (Times Literary Supplement, 26 November 2010). It is true that by the time Sartre became famous, much of his best writing was behind him. Nonetheless, Sartre lived and worked on what we can now identify as a temporal seismic fault-line between then and now. His voluminous and variegated work – short stories, novels, plays, essays, movie scripts, journalism, autobiography, and correspondence, as well as philosophy proper – remains a rich site for investigating the thirty or so years between the mid-1930s and the mid-1960s, that period when, as Thomas Pynchon puts it, ‘a screaming came across the sky’. To re-engage with Sartre is to re-enter the zone of the epicentre, where broken twists of what was once continuous tradition mingle with new developments – some of which we already know to have failed, while others have become familiar features of our present landscape.

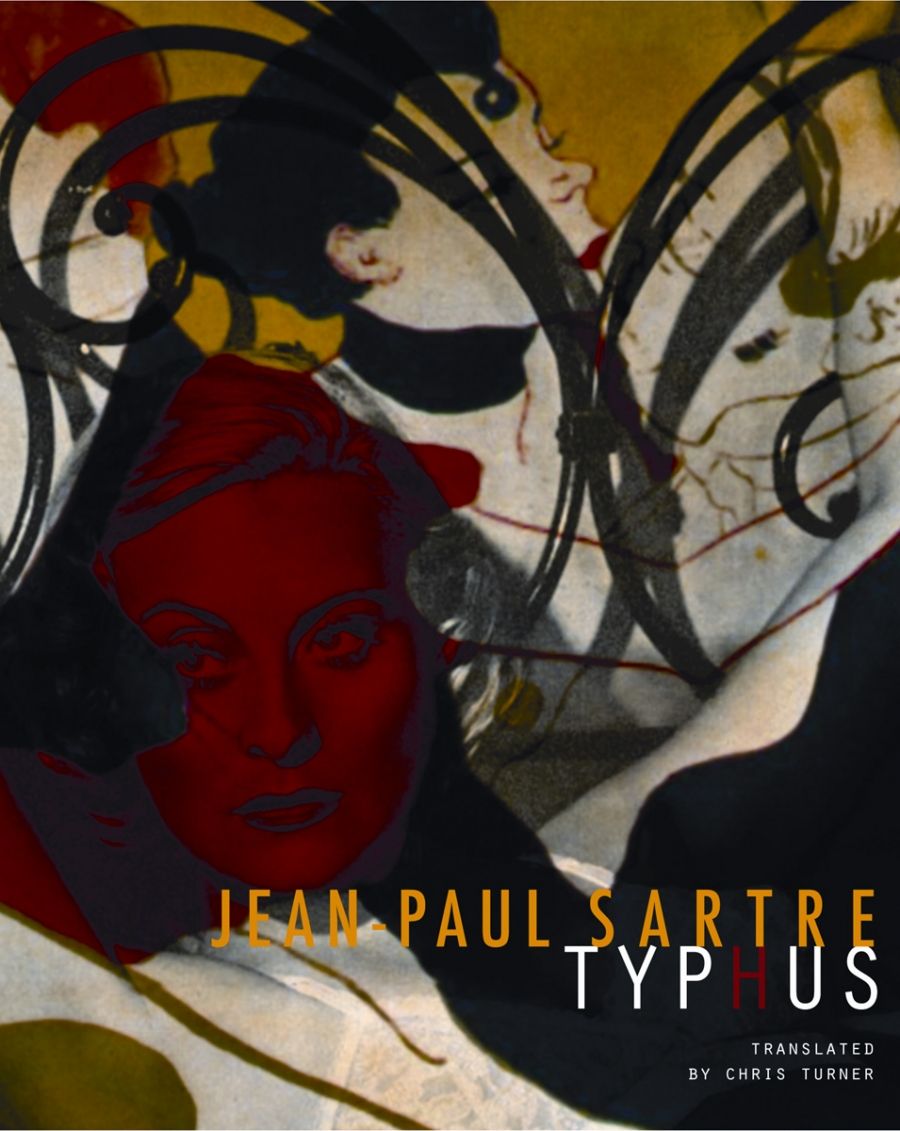

- Book 1 Title: Typhus

- Book 1 Biblio: Seagull Books, $28.95 hb, 212 pp

- Book 2 Title: Critical Essays

- Book 2 Biblio: Seagull Books, $46.95 hb, 554 pp

- Book 2 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 2 Cover (800 x 1200):

- Book 2 Cover Path (no longer required): images/1_SocialMedia/2021/September_2021/9781906497606.jpg

Sartre’s celebrity status has never faded in France. More than a million of his books are sold annually, and many of them have become canonical, such as his first novel La nausée (Nausea, 1938), various of his plays, and the autobiographical work that for many is his chef d’oeuvre, Les mots (Words, 1964). As an agent of change, however, Sartre was pretty much a spent force by May 1968: adulated by the intellectual youth of the post-Liberation decade, for the students of 1968 he was a barely tolerated elder. There is something tragicomic in his antics at this juncture. Fired up by his pseudo-Maoist politics, resolute in his attempts to get himself arrested, he was protected – under strict orders from the highest authority – by the very police he tried to provoke. ‘One does not arrest Voltaire,’ pronounced President Charles de Gaulle. For the rest of his life, Sartre was a prisoner of his fame and, to a great extent, he has remained so posthumously.

That is why Chris Turner’s recent and excellent translations of a number of Sartre’s early writings are so welcome. (In addition to the two reviewed here, Turner has translated the 1964 anthology, Portraits.) Although Typhus is more interesting historically than as a work of art, it has plenty to offer. As for the Critical Essays, they take us straight back into Sartre’s crucible years – into the creative dynamism and the daring but rigorous thinking that brought him to prominence in the first place.

Typhus is the screenplay of a film that was never made. We cannot let pass Arlette Elkaïm-Sartre’s introductory comment that Pathé commissioned this work in 1943 because they sensed the coming Liberation and were looking for a fresh start. This is simply breathing on the coals of the France-as-Resistance myth. The fact is that during the Occupation, the French cinema industry, benevolently controlled by the German censors, ingeniously managed by Vichy bureaucrats, and spared the competition from Hollywood, not only thrived but set in place many of the structures and practices that would ensure its lasting cultural power and status. Sartre saw that cinema was emerging as a major high art narrative form, and he wanted to be part of it.

Set in colonial (British) Malaya during an epidemic, Typhus features a down-and-out cabaret singer, Nellie, who is trying to return to Europe, and a destitute, self-abasing alcoholic former doctor, George, who has gone native. The plot rushes downhill all the way, with little plausible preparation for the redemptive dénouement that sees Nellie and George fall in love as they commit themselves to helping the sick. Thematically, Typhus fits in readily with the rest of Sartre’s work. The links with Les mouches (The Flies, 1943) are particularly strong, and it makes sense to interpret the screenplay as a similar sort of allegory of the Occupation, where oppression distorts individual and social behaviour, and leads to a loss of moral direction. Or again, Nellie’s role as a force of resistance and human decency, and as the vehicle of Sartre’s message of existential freedom and responsibility, prefigures that of Lizzie in La putain respectueuse (The Respectful Prostitute, 1946). What is new and different is the eager deftness with which Sartre embraces cinematographic language. There is great diversity of framing, camera work, montage: sweeping long shots are melded fluidly with close-ups (a foot tapping impatiently, a large fly crawling over the lip of a dying Malay), or with effects such as a scene portrayed through the rear-view mirror of a bus. Image, sound, and dialogue are artfully combined. It has often been observed how Sartre integrated many cinematic techniques into the Le sursis (Reprieve) section of The Age of Reason, which he was writing at the time, and into many of his postwar plays. Beyond the value he derived from cinema for his own narrative strategies, however, Typhus bears testimony to Sartre’s emblematic position in French cultural history: his love affair with cinema is exemplary as well as personal, a significant indicator of how and when France’s centuries-old literary tradition began to treat cinema no longer as an ill-bred upstart, but as an artistic equal and interlocutor.

Sartre’s willingness to interrogate the new – if not always to embrace it – is evidenced throughout the Critical Essays. At first glance, these sixteen texts might seem haphazardly selected, covering as they do both French and non-French writers (Faulkner, Dos Passos, Husserl, Nabokov), canonical figures (Mauriac, Giraudoux), as well as emerging ones (Camus, Bataille, Blanchot) and even the long-dead (Renard, Descartes). But as the first volume of the Situations series – which Sartre imagined as a kind of holistic account-taking of humanity’s place in time, the bringing-to-consciousness that he saw as a precondition of existential freedom – it has many unifying threads. In fact, the anthology of essays becomes an essay in itself, on the one hand offering an overview of the ambiguities and tensions of the cultural ethos of postwar France, and, on the other, constructing a compelling portrait of Sartre himself: the reader, the questioning thinker, the brilliant and ultimately optimistic essayist.

Like Typhus, the Critical Essays stem from a cultural turning point, what the novelist Nathalie Sarraute called the ‘era of suspicion’. This is a world for which, even before the full horror of the Shoah was widely known, the past was devastation, and the future a threat of nuclear annihilation: a world reduced to an uncertain, absurd present tense. Meaning is no longer given or readily available: it has to be created, but can only be created in a quicksand situation that threatens to swallow it up as soon as it emerges. Such is the vision that Sartre confronts in the work of Camus, Blanchot, and Bataille. It is a vision with serious implications for literature: what authority can literary conventions or genres claim, when the very nature of literature and its social function are no longer the object of consensus?

It is no accident that these essays appeared at the same time that Sartre, in Les Temps Modernes, was publishing what would become the second volume of Situations: Qu’est-ce que la littérature? (What is Literature? [1951]) For him, the future of literature was not in the modernist avant-garde as it developed from Baudelaire to the Surrealists, but rather in the bold experiments with narrative viewpoint, time, and space that he finds in Dos Passos, Faulkner, and Camus. If he attacks Giraudoux and Mauriac, it is because he sees their imagined worlds as bathing in a bad faith that ignores the tenuous realities and relativities of the contemporary human condition. The essay on Mauriac is a luminous defence of readerly freedom, and especially the right not to be led by an omniscient narrator through a preordained universe governed by destiny and character.

A number of the essays probe beyond the question of literary forms, into the reliability of language itself. This is the focus in the pieces on Bataille, Blanchot, Parrain, Ponge, and Renard. As Sartre attempts to map, in words, the impact on human experience of the dissociation of words from the phenomenological world, an intriguing struggle emerges, and it reveals that, while acknowledging the vulnerability of language in times of extreme political or social stress, he refuses to lose faith in it altogether and indeed, as the essay on Bataille makes clear, believes that it is folly to do so. Significantly, the language in which he believes is not the narrowed language of the sciences or of scientistic epistemologies such as behaviourism; rather, it is that of the great thinkers and writers who have informed and enriched human freedom over the centuries.

To that extent, Sartre remains a traditionalist. Indeed, when faced with the extreme radicalism of a Bataille, he manifests a cautious, even conservative, streak, demonstrating that he does not value transgression for transgression’s sake any more than art for art’s sake, and that he believes that true revolution has to be constructive. Yet at the same time, each of the essays is patently born of a desire – and a willingness – to understand its subject, and each contains a thoroughgoing analysis of the work on its own terms before the critique is applied. Sartre is a generous reader, and it is vivifying to accompany this powerful, imaginative, amazingly well-read mind as it seeks ‘to plumb the human condition more deeply’. Admittedly, there are irritants, especially the smug superiority that often shows through, but, whatever its flaws, Sartre’s thought never loses track of what matters most to him: the freedoms and contingencies that determine our place in the world.

When he praises Descartes for his ‘magnificent humanistic affirmation of creative freedom’, Sartre could have been describing the thrust of his own essays. On almost every page of this book, he invites his readers to choose their freedom, and to choose it radically and courageously against the seemingly unbending constraints that crowd in on them. This is a call to optimism, but it comes with the weight of belief in a common responsibility for humanity that makes today’s individualistic hedonisms look decidedly flimsy; no kind of real freedom at all.

Comments powered by CComment