- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Poetry

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Gorgeous traffic

- Article Subtitle: Tracy K. Smith’s marine vitality

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

‘The wave always returns’, writes Marina Tsvetaeva. And it ‘always returns as a different wave’. Such Color reveals such a relentless renewal of lyricism as a signature of Tracy K. Smith’s poetry. A selected edition promises to highlight images and ideas across the American poet’s work. For Smith, one constant is the movement of water. In ‘Minister of Saudade’, from her second collection, Duende (2007), the speaker asks: ‘What kind of game is the sea?’ After a pause at the stanza break, an incantatory reply comes: ‘Lap and drag. Crag and gleam. / The continual work of wave / And tide.’ Ceaseless making, flux, and patterning are also a poem’s work. Smith’s image of creative marine energy recalls Sylvia Plath’s image of words’ ‘indefatigable hooftaps’, echoing as they carry meaning outwards. In Plath’s case, as in Smith’s, one direction is seawards.

- Article Hero Image (920px wide):

- Article Hero Image Caption: American poet Tracy K. Smith (photograph by Rachel Eliza Griffiths)

- Alt Tag (Article Hero Image): American poet Tracy K. Smith (photograph by Rachel Eliza Griffiths)

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Felicity Plunkett reviews 'Such Color: New and selected poems' by Tracy K. Smith

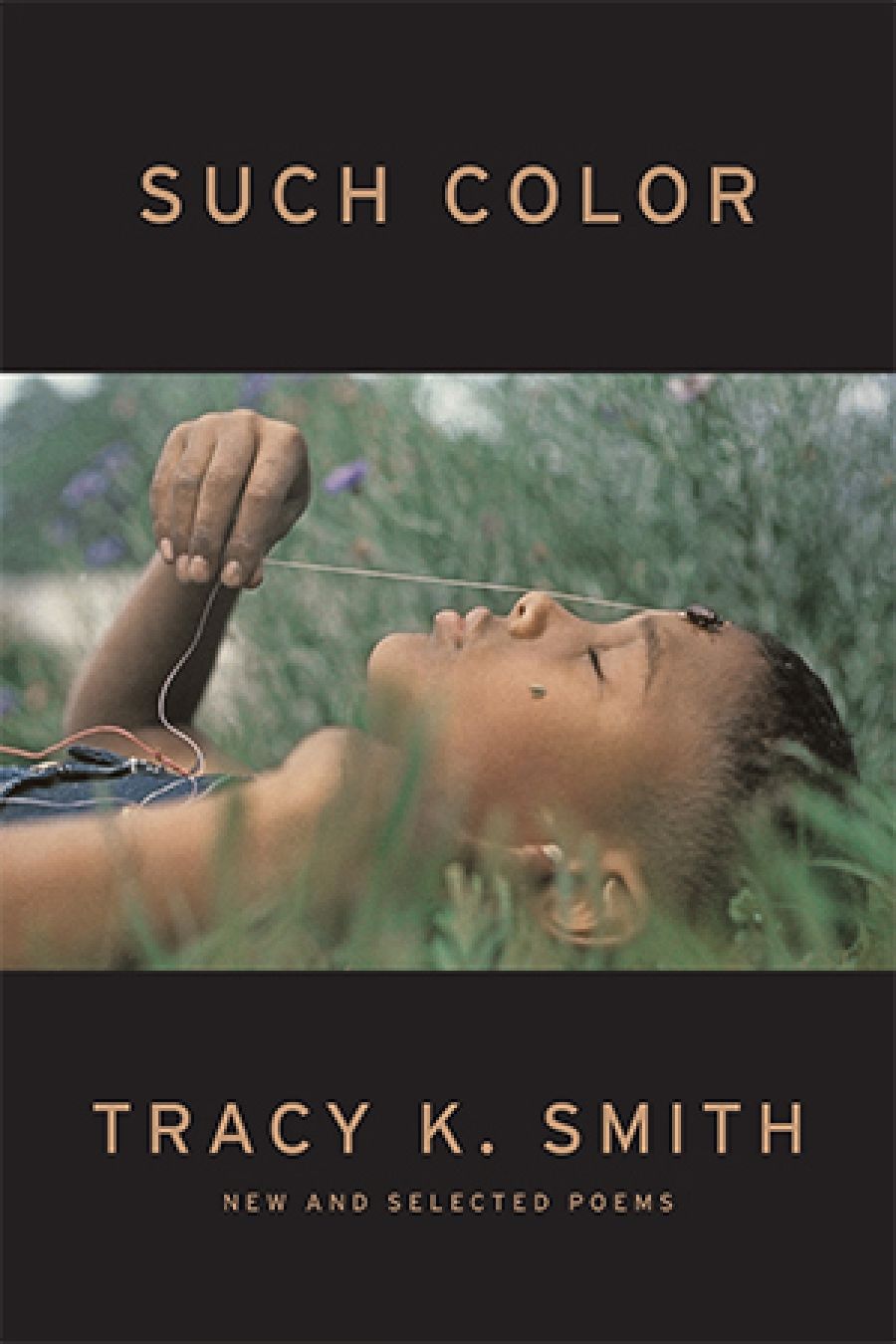

- Book 1 Title: Such Color

- Book 1 Subtitle: New and selected poems

- Book 1 Biblio: Graywolf Press, $46.90 hb, 221 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/BXBVW9

The sea’s ‘continual work’ is also time’s work of making and unmaking, cresting and dragging. Time’s leaps and stasis form part of Smith’s poetic practice, especially in her treatment of history’s layers, brought to the light in many poems. Her metaphors are restive, moving like spectres between objects and ideas. In The Art of Daring: Risk, restlessness, imagination (2014), poet Carl Phillips suggests that we are ‘each of us, uniquely haunted’.

Such Color traces the shapes of Smith’s ghosts and hopes, the duende that gives her second collection its title. Federico García Lorca felt the duende, a spirit of passion and inspiration, demanded the renewal of forms, bringing ‘to old planes unknown feelings of freshness’. This collection assembles selected poems from Smith’s four previous collections with the eighteen dazzling new poems collected under the section title ‘Riot’.

The Body’s Question (2003) establishes the metaphorical grammar of Smith’s poems. Bodies in water recur. The lake in ‘Drought’ lures a boy to its ‘cold, cold center’ where the syllables of his called name strive and ripple towards him like thrown stones. Or water is itself a body. The river is ‘a wide, black, furious serpent’ in ‘Gospel: Luis’.

There are waves ‘the color / Of atmosphere’ (‘Thirst’), as air and water shadow one another (‘Gospel: Jesús’). Lovers’ bodies swim together in afternoon light (‘Credulity’). Timelessness is imagined as sea when recognition sparks: ‘We were souls together once / Wave after wave of ether / Alive outside of time.’

As Kevin Young writes in the introduction to the full collection The Body’s Question, using Smith’s own phrases to mirror her work, ‘her lines themselves [are] a “gorgeous traffic” that “mimics water”’. A repeated word slips back into the poem in a phrase broken over the line, ghostly and uncanny. ‘You are pure appetite. I am pure / Appetite’, says the speaker in ‘Self-Portrait as the Letter Y’. Insistent images undo and remake themselves.

Appetite is another current through Smith’s work, and one of the body’s questions is desire. ‘Getting to what I want’, says the speaker of ‘Joy’, ‘will be slow going and mostly smoke’, like thwarted efforts to coax kindling into flame.

The question of what a poem can do pulses through Duende. If ‘[e]very poem is the story of itself. / Pure conflict. Its own undoing’, history may be a lie a poem can undo. Knowing this, there are some ‘who don’t want the poem to continue’, but can’t be sure it’s ‘important enough to silence’. This includes personal histories of loss. There is a ‘sea in my marriage’, where the speaker of ‘El Mar’ sits in a ‘tiny house afloat / On night-colored waves’. But Smith, in a recent interview with Paul Holdengräber on The Quarantine Tapes, describes a commitment to bringing to her various contexts ‘the vocabulary of justice and anti-racism’. So the poem is also a boat carrying ‘a hundred bodies at prayer’, witnessing the theft of freedom.

Smith’s ‘I’ expands from the sensual ‘I want, I want’ of a poem like ‘One Man at a Time’ to move between speakers and over time, yet she identifies the pernicious nature of the ‘huckster, trickster’ ‘we’: ‘We has swallowed Us and Them. / You will be next to go.’ This ‘we’ assumes its own dominion, as in ‘we the people’. Instead, Smith creates choral poems from eclipsed or lost voices, such as the kidnapped teenagers given as ‘wives’ to the rebel commanders of the Lord’s Resistance Army in Uganda.

Poems of witness return in Wade in the Water (2018), a book about racism and hate that refuses to relinquish love. It begins with ‘The Angels’ and two grizzled angels watching over a sleepless speaker who is ‘worn down by an awful panic’ in a scruffy hotel room, and who comes to marvel that ‘they come, telling us / Through the ages not to fear’. The angels, joy, and love that return to Smith’s poems are more vital for the violence they survive.

Before Wade in the Water was Smith’s Pulitzer Prize-winning Life on Mars (2011), a book-length elegy for her father, a scientist who worked on the Hubble Telescope. The title is borrowed from David Bowie, and its sonnet coda addresses the ‘small form’ who ‘tumbled into’ her at the moment of conception.

‘The wave after wave is one wave never tiring’, writes Smith in a poem of the same name in ‘Riot’. On the ‘far shores / of the nationless sea’, trees remember lynchings, while a speaker wonders ‘What if / the world has never had – will never have – our backs?’ With found text and poems responding to violent language Smith shows indefatigable commitment to the continual work of justice and witness. Around this injustice, rapture and light persist, and the collection closes with the repeated phrase: ‘We live –’.

Comments powered by CComment