- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Graphic Novel

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: On the home front

- Article Subtitle: Picto-critical eyes on the Vietnam War

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Editorial cartoonists gamble their all on a same-day art, their work created, read, and discarded on the day of publication. The makers of graphic novel journalism use the language of cartooning, too, but in their case it’s a marathon, not a sprint: they spend years arranging thousands of images and tens of thousands of words across hundreds of pages in order to create their books. Two new graphic novels cast a picto-critical eye on the war in Vietnam and show how it came home to roost, bringing death and imprisonment to suburban streets in Australia and the United States.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Bernard Caleo reviews 'Kent State' by Derf Backderf and 'Underground' by Mirranda Burton

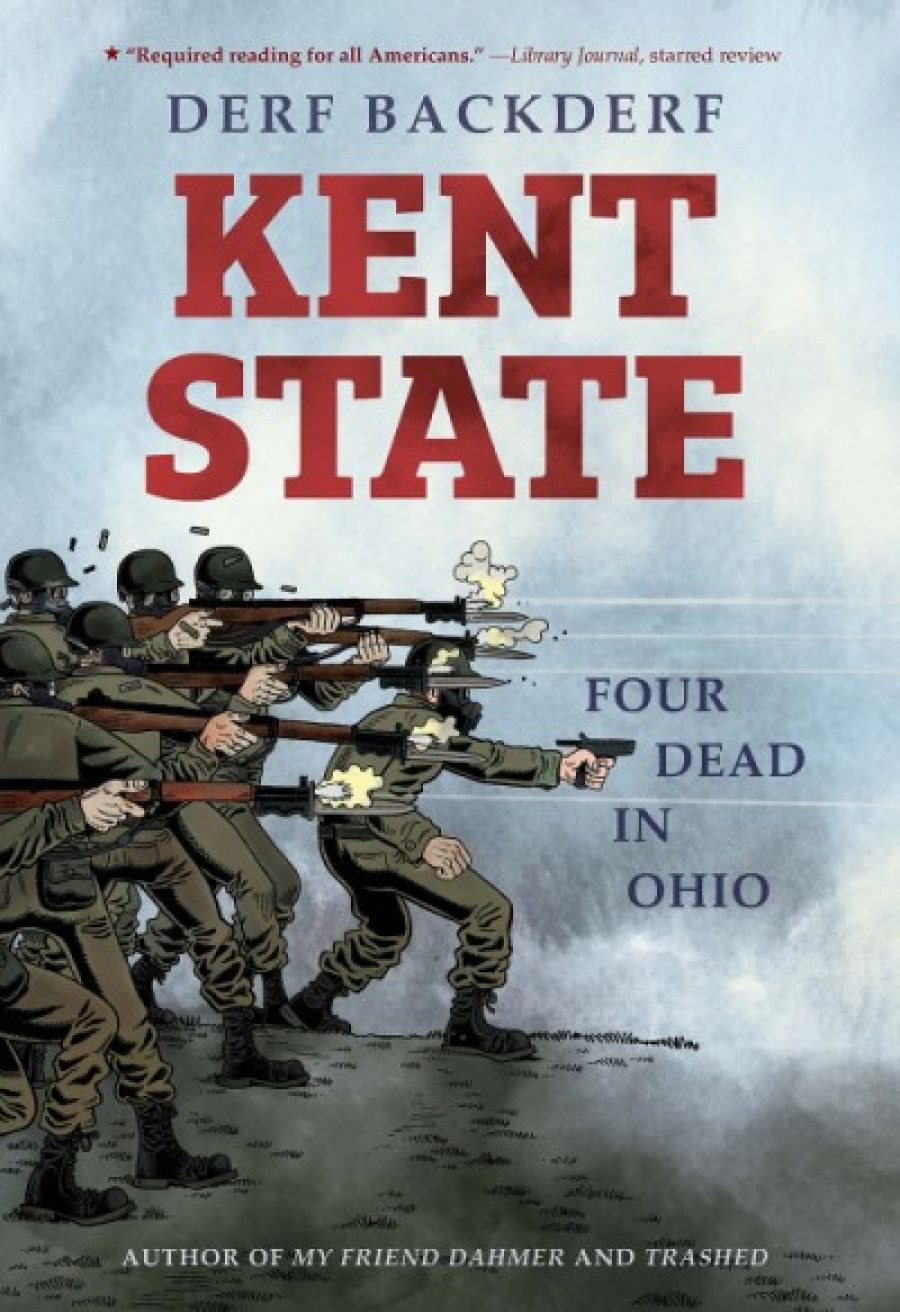

- Book 1 Title: Kent State

- Book 1 Biblio: Abrams ComicArts, US$24.99 hb, 288 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/x9OoBR

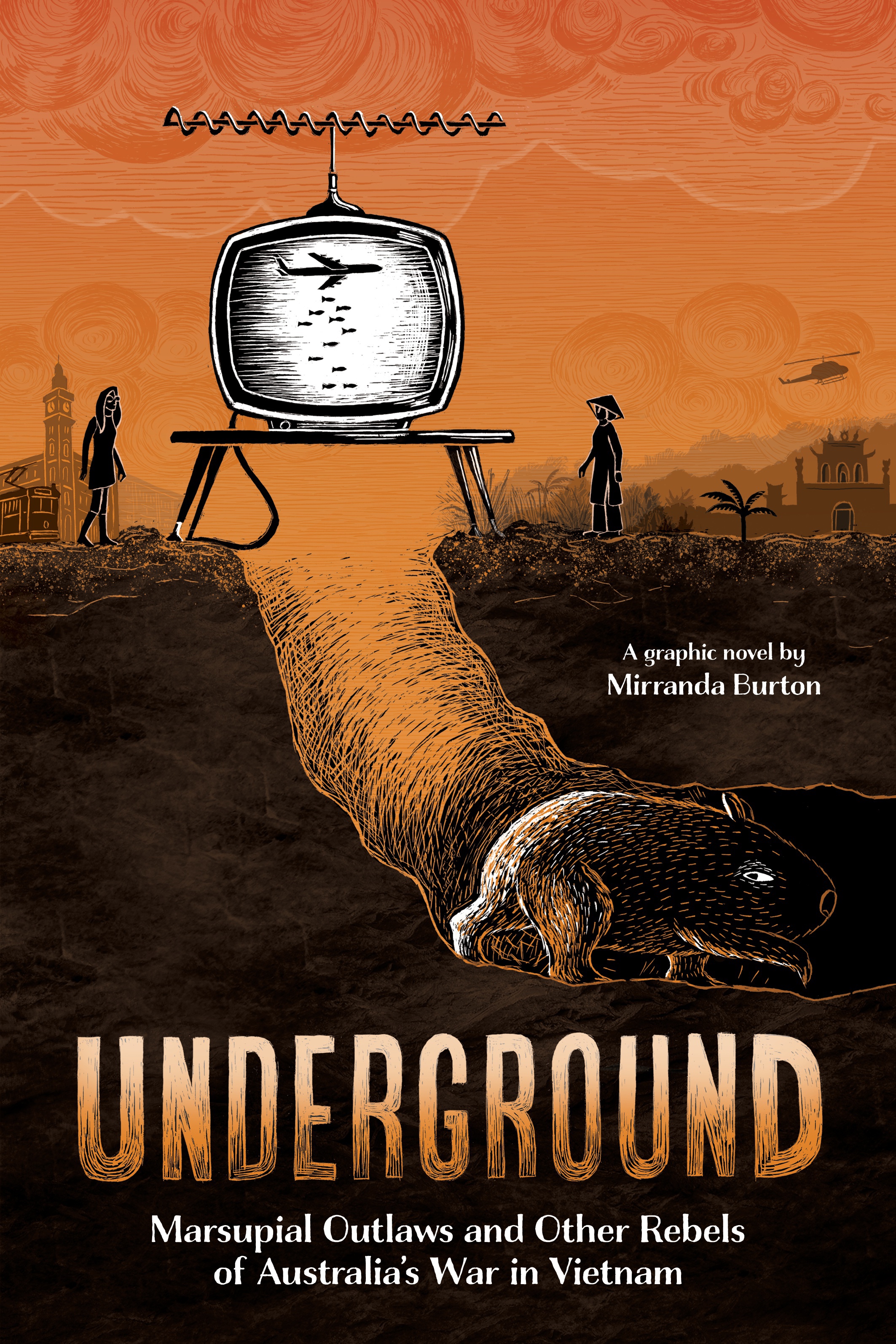

- Book 2 Title: Underground

- Book 2 Biblio: Allen & Unwin, $29.99 pb, 272 pp

- Book 2 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 2 Cover (800 x 1200):

- Book 2 Cover Path (no longer required): images/1_SocialMedia/2021/Dec_2021/META/Underground.jpg

- Book 2 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/LPgEJo

A major challenge for historical comics is scene-setting: Backderf has a lot of information to convey in order to establish the political power blocs and social ruptures that led to the Kent State shootings. There’s the Students for a Democratic Society (SDS), which by 1968 has 100,000 members. There’s the Weathermen, the militant radical wing of the SDS, which declares war on the Nixon administration and bombs multiple US targets in 1970. Their violence and ‘cartoonish militancy’ (Backderf) mandate the extreme measures taken by the FBI against them, but also drives widespread desertion of the SDS as more pacifist students distance themselves from the Weathermen’s violent tactics. In the town of Kent, Backderf describes a sharp social and political divide between the older, more conservative townsfolk and the university population. He is particularly good at delivering the tenor of student life: sharehouses, music practice, smoking joints, listening to the new Paul McCartney solo album, and meeting friends at the bars on Water Street. He does choose to deploy text-heavy pages in order to bring us up to speed with various aspects of 1970s America, Kent, and campus life. Almost two pages of illustrated text are needed to explain the Reserve Officers’ Training Corps (ROTC), an on-campus building housing a program for training officers (5,000 of the 6,600 commissioned officers who died in Vietnam were ROTC graduates), but these infrequent wordy pages are buttressed by sequences of dialogue and action, so they don’t break your reading rhythm. For example, when the Kent State University ROTC building is destroyed on 2 May, and more National Guardsmen are called in, the tension builds until the students stage a sit-in protest on a street in town, which Backderf depicts using a full-page image on which the only words are the chant, ‘Guard off campus!’

Backderf’s cartooning style follows solidly in the tradition of the US underground cartoonists of the 1960s and 1970s (artists like Robert Crumb and Spain Rodriguez) as well as MAD magazine – it’s a ‘dirty realism’ cartooning, unafraid of exaggeration and the grotesque. Given these 1970s comics history roots, his cartooning style matches the temporal setting of the tale and in fact lends it an added layer of verisimilitude.

A page from Underground by Mirranda Burton

A page from Underground by Mirranda Burton

Closer to home, Mirranda Burton’s Underground: Marsupial outlaws and other rebels of Australia’s war in Vietnam tackles the impact of the war on the streets and people of Melbourne and Saigon. The central human character is Jean McLean, who became the convenor of the Victorian branch of the Save Our Sons movement in 1965. We also follow Bill Cantwell, an Australian soldier who serves in Vietnam, and Mai Ho, who escapes to Australia by boat with her daughters after the war. All three now live in Melbourne, and one of the satisfactions of this book is seeing how Burton braids these lives together. Burton’s background as a printmaker is evident in Underground: in addition to her ‘straight’ cartooning storytelling, there are pages where she utilises a scratchboard approach, which lends a more ‘open’, less time-bound quality than that of her comics frames sequences. This helps her narrative to breathe, which is important because she is covering so much more ground than Backderf (decades, not days); compression of character and event becomes inevitable.

Underground ’s marsupial is a wombat adopted by Marlene Pugh and her artist husband, Clifton, in 1969 on their bush block home north of Melbourne. During an artist’s residency there forty years later, Burton stumbled upon the story of Hooper Algernon Pugh, ‘the wombat who wouldn’t do combat’. A 1970s anti-war technique, the ‘fill in a falsie’ campaign had protesters registering pets and ancient philosophers for conscription as a way of wasting the time and resources of the National Service Office. When the police arrive at Dunmoochin in 1972 seeking Hooper, who’s been called up, Clifton Pugh describes him: ‘Short fellow. Very large nose. Small ears.’

These two graphic novels examine fifty-year-old wounds in the national lives of three countries. Because comics traffic in icons (conveying more meaning with less information), they can shuttle between iconic figures (Richard Nixon, Gough Whitlam) and ‘ordinary’ people (such as Jean McLean) and imply, via comics’ sequential logic, causalities between these strata in human affairs. Both books solve, in different ways, the problematic requirements of expository dialogue and text-heavy pages so that the reader has enough information to understand the historical period. Burton’s characters are restrained, modest, polite – in a word, Australian. Burton’s is a quiet book, Backderf’s more strident, but both deploy the tactility and immediacy of graphic novels to persuade their readers to feel the human cost of the Vietnam War on the home front.

Comments powered by CComment