- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: History

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Gone fishin’

- Article Subtitle: History in cupfuls

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

In early 1961, historian Edward Hallett Carr (1892–1982) delivered a series of lectures on his craft. The resulting book, What Is History?, was a provocation to his peers and a caution against positivist views of the past. He urged the reader to ‘study the historian before you begin to study the facts’. He illuminated the subjectivities of the historical process, from the moment a ‘fact’ occurs to when it is called as such, through the endurances and erasures of archival selection to the silences created by the historian’s narrative choices. The most famous passages are Carr’s maritime metaphors, in which he likens ‘facts’ to ‘fish swimming in a vast and sometimes inaccessible ocean’. What the historian will catch depends on the kind of facts she wants, and once they reach the fishmonger’s slab, she will cook and serve them ‘in whatever style appeals’. ‘History,’ Carr concluded, ‘means interpretation.’

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Billy Griffiths reviews 'What Is History, Now? How the past and present speak to each other' edited by Helen Carr and Suzannah Lipscomb

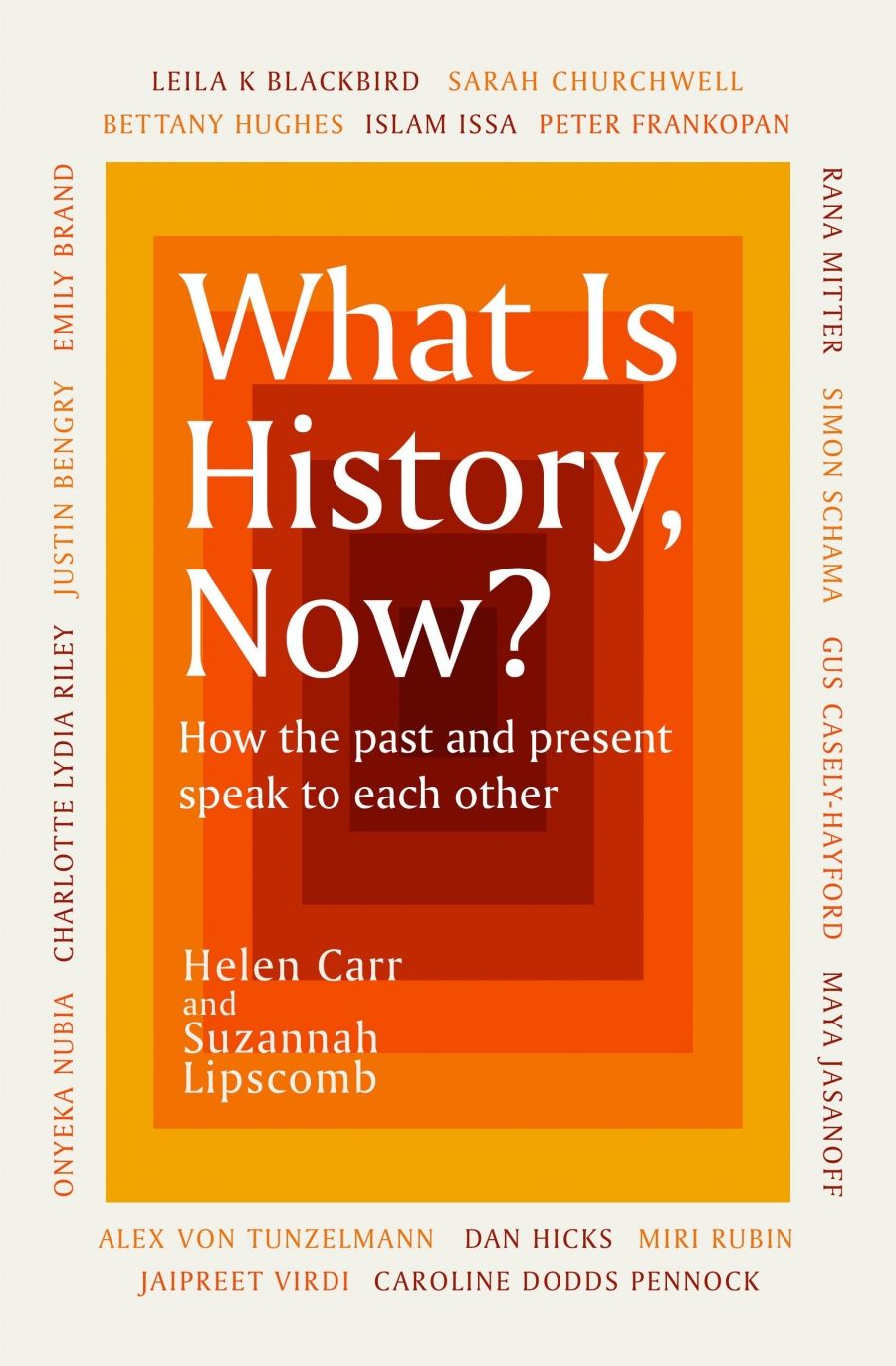

- Book 1 Title: What Is History, Now?

- Book 1 Subtitle: How the past and present speak to each other

- Book 1 Biblio: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, $32.99 pb, 339 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/AoBaxD

Sixty years later, Carr’s great-granddaughter Helen Carr, together with Suzannah Lipscomb, has revisited the classic text in a new edited collection, What Is History, Now? Helen Carr was born six years after her great-grandfather died, but she grew up with stories of ‘the Prof’, and throughout her life has engaged in an imagined dialogue with him, ‘one of our greatest and most influential historians and thinkers’. She hopes this collection will serve ‘as a tribute to Carr’s timeless work’ as well as ‘an olive branch to those who have felt pushed out or marginalised from history’. (I wonder what E.H. Carr, the great advocate for context, would make of his work being called timeless?)

Lipscomb shares Helen Carr’s inclusive vision for history. As she reflects in her individual contribution, ‘if we keep on telling the same stories of the people in power … we will be complicit in keeping the marginalised marginal’. Together they have commissioned and curated an engaging, if inconsistent, series of essays about reading into silences, writing histories ‘against the grain’, and recentring peripheral voices.

But the question in the title – ‘What is history?’ – is no longer active in this new volume. This book is neither a historiographical argument nor a review of the past sixty years of scholarship; rather, it is a showcase of the variety of history-writing currently underway in Britain and America. History, in Carr and Lipscomb’s framing, is a stable, clearly defined discipline based on documents. It is distinct from other disciplines, such as literature, archaeology, and ‘prehistory’, and can be ‘flexible, malleable, colourful and without bias’. It is something to be accessed or enjoyed or extended to others. And while they suggest that ‘history belongs to us all’, they regard history-writing to be the domain of professional, mostly academic, historians.

If this seems a narrow framing of ‘history’, fortunately it has not stopped the contributors from bursting disciplinary boundaries and celebrating, in Bettany Hughes’s words, ‘that there are as many ways to understand history and to enact historiography as there are ways to be human’. Indeed, Leila K. Blackbird and Caroline Dodds Pennock explore how Indigenous perspectives are subverting and enriching ‘European ways of understanding and telling history’. And in the final essay in the volume, Simon Schama bristles at the perceived need to seek ‘permission from the academy’ to engage with archives other than documents. ‘Is natural history history?’ he asks. ‘How could it not be, when the epic of the earth circumscribes everything else historians write about?’

This is far from the first book to revisit Carr’s text, and it is similar in structure to earlier efforts, such as David Cannadine’s 2002 collection, What Is History Now? It not only shares a title (overlooking the comma) but also a contributor. While the chapters in the Cannadine collection offer historiographical reviews of some of the branches of history (i.e. ‘What is social history now?’), the chapters in this collection act as pitches for the value and necessity of various subdisciplines: ‘Why global history matters’, ‘Why diversity in Tudor England matters’, ‘Why family history matters’. Far from conjuring the ‘vast ocean’ of historical experience, this bite-sized approach brings to mind a different maritime metaphor: Gustave Flaubert’s jibe that ‘writing history is like drinking an ocean and pissing a cupful’. But I level this criticism at the framing of the book and not at the contributor chapters, which, more often than not, runneth over.

There is an activist, revisionist spirit throughout the collection. Representation is a recurring theme. Jaipreet Virdi asks why disability – such an enduring part of human experience – is so conspicuously absent from historical discussions: ‘the people whose histories have long been glossed over, trapped in medical files or valued only for inspiration need their stories told’. Justin Bengry builds on this theme in his chapter on queer history, where he finds ‘ancestors and aliens in the very same people’. ‘Having a history matters,’ he writes. ‘That the past is ultimately so full of possibility must challenge us to reconsider our own times.’

Unfortunately, Carr and Lipscomb’s interest in representation does not extend to geographical representation. Several contributors call for broader, non-Western perspectives, especially given the geopolitical dynamics of the twenty-first century. Indeed, Maya Jasanoff, in her critique of imperial histories, even calls out the ‘disproportionate concentration of resources and “authority” in the well-endowed universities of former colonial metropoles’. Yet this legacy of empire remains on full display in What Is History, Now?, with its dominant northern-hemisphere focus.

The most interesting strand is the exploration of history as a way of thinking: as a process of questioning and querying, of making informed judgements about reliable or unreliable sources, of contextualising, synthesising, empathising, and understanding. As Alex von Tunzelmann argues, the craft of history is a vital tool in the age of misinformation. ‘History gives us all the time in the world to think,’ writes Hughes. ‘History reminds us to remember, to think better.’

What is sometimes lost in this collection – and particularly in the way it has been framed – is the idea of history as a creative act: a performance of critical imagination. The editors’ assertion that history can be written ‘without bias’ undercuts more interesting conversations that could be had about the limits of the historical imagination, the interplay between history and fiction, and the idea that a work of history can also be a work of great literature. Similarly, flippant remarks such as ‘As we write, history is hot stuff’ undermine the gravity of their subject. History is always political. It is not just a discipline that moves in and out of the public eye. It is an endless, dynamic dialogue between past and present.

There is little that is ground-breaking in this collection, but that doesn’t stop it from being lively and rewarding. It is well suited to graduate historians in search of a specialty. If you are looking for robust historiography, turn to one of the other hundreds of books that have used E.H. Carr’s writing as a spur to historical thinking. If you crave an elucidation of the subtleties, complexities, and magic of history, search out a single-authored book, perhaps even by one of these talented contributors, where they have the space to develop a voice, cultivate an argument, and show, as well as tell, what good history can be.

Comments powered by CComment