- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Publishing

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: A tidy little earner

- Article Subtitle: Peter Ryan meets his match

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

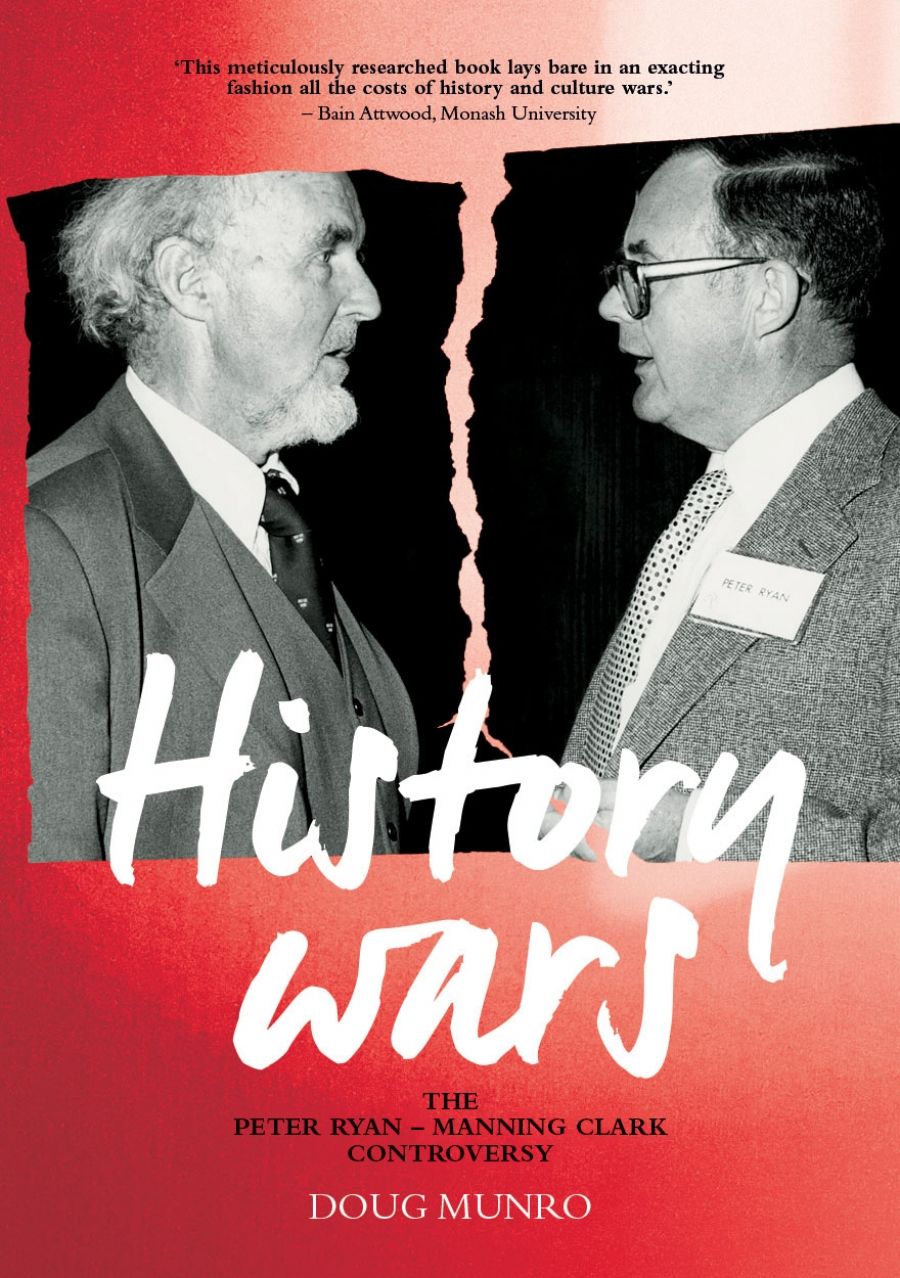

It was one of the most notorious episodes in the annals of Australian publishing. In September 1993, writing in Quadrant, Peter Ryan, the former director of Melbourne University Press (1962–87), publicly disowned Manning Clark’s six-volume A History of Australia. Clark had been dead for barely sixteen months. For scandalous copy and gossip-laden controversy, there was nothing to equal it, particularly when Ryan’s bombshell was dropped into a culture that was already polarised after more than a decade of the History Wars.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Mark McKenna reviews 'History Wars: The Peter Ryan–Manning Clark controversy' by Doug Munro

- Book 1 Title: History Wars

- Book 1 Subtitle: The Peter Ryan–Manning Clark controversy

- Book 1 Biblio: ANU Press, $55 pb, 229 pp

Almost twenty years since Ryan’s article appeared, Doug Munro, one of New Zealand’s finest historians, has given us the first comprehensive account of the entire saga, providing insightful biographical and political context, excavating every morsel of intrigue and drama, and skilfully revealing the controversy’s lasting significance. In a tenacious scholar such as Munro – a historian of the Pacific who has recently published widely on the lives of historians – Ryan has met his match.

Munro became interested in the controversy gradually, but as he read more and more, he was convinced that ‘Ryan’s version of events didn’t stack up’. Nor was it ‘trustworthy’. ‘I am no more enamoured of Clark now than I have been in the past’, he explains, ‘but I believe that Ryan behaved badly’ and that he ‘emerges from the episode with little credibility’. One of the key questions that Munro is driven to answer concerns Ryan’s motivation. Why did he attack Clark with such ferocity? Why so soon after Clark’s death? And what drove him to abandon his professional obligations as Clark’s publisher for more than twenty-five years?

In May 2007, when I interviewed Ryan for my biography of Manning Clark (An Eye for Eternity, 2011), it was clear that merely talking about Clark seemed to animate every fibre of his being. Ryan lurched from affection for Clark to outright hostility in the same breath. ‘Even when I disapproved of him I didn’t regret knowing him’; ‘he was a complete fucking hypocrite’; ‘he needed to be buoyed’; ‘he was a bad man’; ‘he was an exhibitionist ... he was always trying to be in the public eye’. Ryan was also deeply conflicted about their relationship. ‘We never had a row’; ‘he was a fucking nuisance’; ‘we shared a frame of allusion’; ‘I could set my watch by Manning’s calls at 9.30 on a Monday morning ... he would often call in one of his gloomy moods ... I’d intentionally save a few bawdy tales or pub stories each week to cheer him up’; ‘[My negative view of his work] was an emerging thing’; ‘What I was doing was my duty to the firm, looking after the best interests of MUP with one of our best-selling authors ... I wished I hadn’t had to be his publisher’.

The two men had known one another since their university days in Melbourne in the 1940s. Ryan had fought in World War II, and in 1959 published a classic account of his time on patrol in New Guinea, Fear Drive My Feet. Clark did not enlist because of his petit mal and, as Peter Coleman noted, was ‘indifferent to the ex-serviceman ethos’. The differences in personality between them were stark. Ryan was fastidious, officious, and cunning. Clark was melodramatic, needful, and self-centred. And as Ryan often moaned to others, he was far from being a ‘compliant author’.

Manning Clark at the University of Newcastle, 1980. (Courtesy of the University of Newcastle Photographic Collection, Special Collections, The University of Newcastle, Australia)

Manning Clark at the University of Newcastle, 1980. (Courtesy of the University of Newcastle Photographic Collection, Special Collections, The University of Newcastle, Australia)

In his later years, Ryan sounded embittered. Something in him was unfulfilled. To my mind, there was little doubt that his view of himself was deeply entangled – emotionally, intellectually, and professionally – with his view of Clark. He was envious of Clark’s extraordinary success and, in 1993, increasingly opposed to Paul Keating’s republicanism and the progressive left politics that Clark had championed vigorously since the early 1970s.

Munro shows that Ryan, who had stopped voting Labor in 1975, was eager to establish his own credentials as a writer in the wake of his retirement from MUP. In early 1993, he had lost his fortnightly column in The Age and was soon offered a column in Quadrant, where he would continue to write until shortly before his death in 2015. He quickly saw the advantage in trying to destroy Clark’s posthumous reputation. Taking the axe to a tall poppy became a way of elevating his own status as a public figure and endearing himself to his fellow conservatives.

Robert Manne has always defended the publication of Ryan’s article. Clark, he argued, was ‘cavalier with facts, unreliable in his mastery of documentary sources, [and] uninterested in the work of other historians’, a reasonably accurate assessment of Clark’s scholarship with which Munro largely concurs. But through a combination of meticulous research and savvy political instinct, Munro scuttles nearly all of Ryan’s justifications for publicly denouncing Clark.

He shows that Ryan was not locked into a contract with Clark, nor was it clear from the outset how many volumes of the history would be published. When Clark became depressed and disillusioned by reviews and threatened to stop, Ryan urged him on, mixing flattery with perfectly timed cheques against Clark’s advance to keep MUP’s ‘tidy little earner’ on track. Nor was there a conspiracy of silence in the academy regarding the quality of Clark’s scholarship. Much of Ryan’s critique had already been aired by others. Ryan’s essay was hardly original. It was not what was said about Clark that was controversial, so much as who was saying it. The dubious decision of a major publisher to publicly dump on his firm’s most successful author was, if nothing else, sensational.

As for Ryan’s motives, Munro is unsparing. Although Ryan had privately expressed reservations about Clark’s work to others, he ‘lacked the intestinal fortitude to confront Clark about the shortcomings of the History’ while his author was alive. Then, when Clark was dead and could no longer respond, Ryan, driven by ‘sheer vindictiveness’, ‘professional jealousy’, ‘political differences’, and ‘a desire to restore his public profile’, skewered the author who had helped to establish his reputation (along with figures like Richard Walsh and Hilary McPhee) as one of Australia’s leading publishers in the late twentieth century.

Munro rightly asks, ‘what does a controversy that basically lasted a fortnight as a media and talkback radio event mean to us thirty years later?’ In his rigorous examination of the whole affair, he has allowed us to see the damage wrought by one episode in the history and culture wars that have plagued Australian literary, intellectual, and political life for almost five decades. I doubt that a more definitive account will be published for many years, if ever.

Comments powered by CComment