- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Letter collection

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: ‘In God’s vineyard’

- Article Subtitle: Writing to a prime minister

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Letter writing thrives on distance. Out of necessity, in the early years of European settlement, Australia became a nation of letter writers. The remoteness of the island continent gave the letter a special importance. Even those unused to writing had so much to say, and such a strong need to hear from home, that the laborious business of pen and ink and the struggles with spelling were overcome. Early letters reflected the homesickness of settlers as well as their sense of achievement and their need to hold on to a former life. It’s possible to see the emergence of a democratic tradition of letter writing in those needful times. Rich or poor, well educated or semi-literate, they all felt the urge to connect.

- Article Hero Image (920px wide):

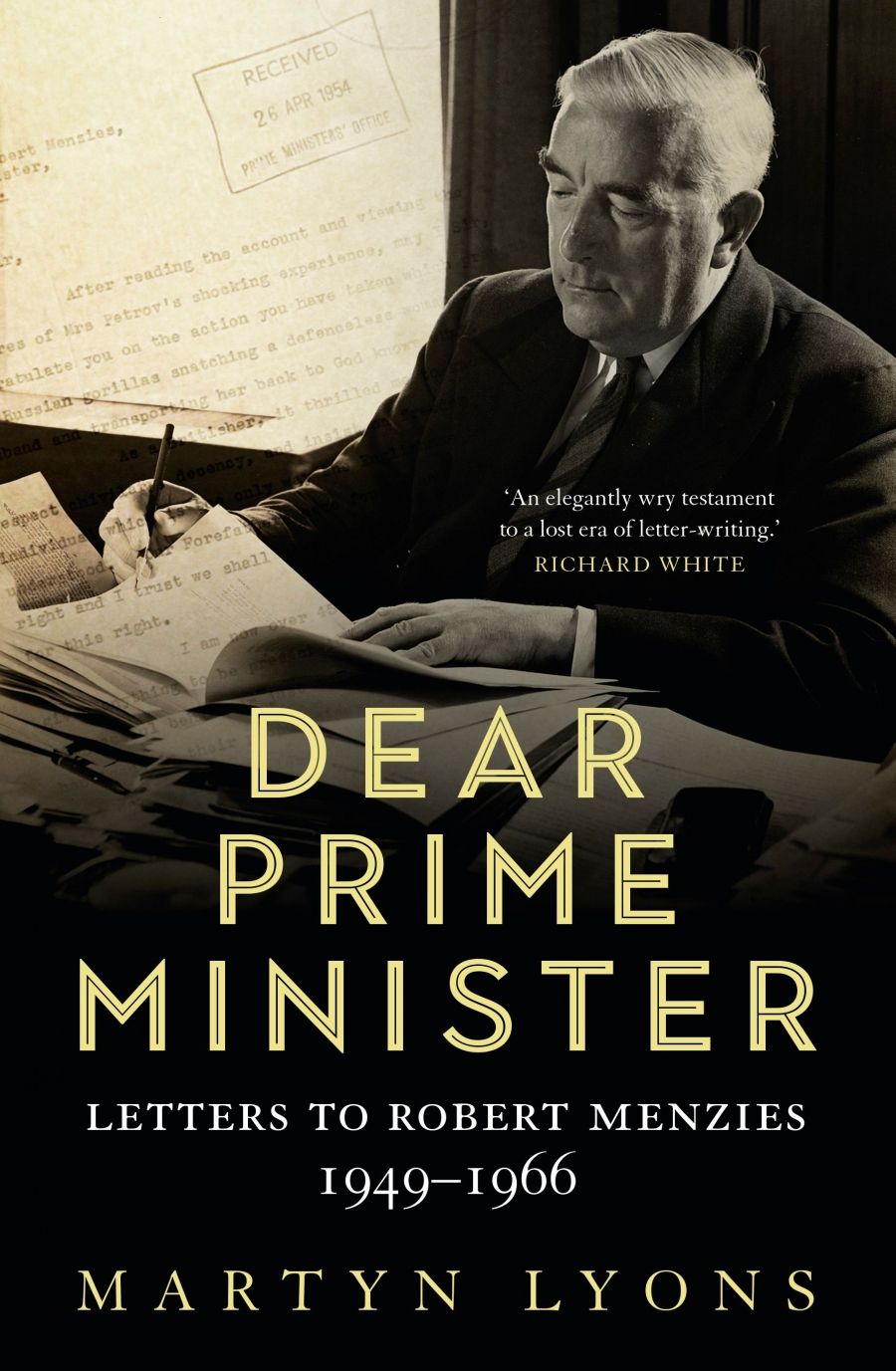

- Article Hero Image Caption: Prime Minister Robert Menzies in 1956 (Trinity Mirror/Mirrorpix/Alamy)

- Alt Tag (Article Hero Image): Prime Minister Robert Menzies in 1956 (Trinity Mirror/Mirrorpix/Alamy)

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Brenda Niall reviews 'Dear Prime Minister: Letters to Robert Menzies, 1949–1966' by Martyn Lyons

- Book 1 Title: Dear Prime Minister

- Book 1 Subtitle: Letters to Robert Menzies, 1949–1966

- Book 1 Biblio: UNSW Press, $39.99 pb, 272 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/NKXP5O

A letter is a transaction between writer and recipient; it speaks of their relationship. The undelivered messages that drove Herman Melville’s Bartleby to despair were called ‘dead letters’. Letters sent to unknown officials in anger, praise, or supplication often bring bland replies: formal thanks that close the door on any further correspondence. The lucky few open up a conversation.

It is mostly one-way traffic in Dear Prime Minister: Letters to Robert Menzies 1949–1966. Historian Martyn Lyons has trawled through the archives to read 22,000 letters in which the needs and passions, obsessions and grievances, of many Australians and some overseas correspondents are revealed. By today’s standards, Menzies had a minuscule staff to deal with his mailbox; and because more than half the letters were handwritten, it was hard work to read, reply, and in some cases refer to the prime minister for comment.

Lyons describes the letters to Menzies as ‘writing upwards’. Many, but by no means all, are deferential. By directing applause or anger at the top level, the writers are acknowledging the prime minister’s authority. Lyons has sorted his immense swag of letters into five main categories. These are the congratulatory letters, the letters that express anger and protest, those that request favours, those that give advice, and the paranoid letters.

The fan mail and congratulation group is the most predictable and respectful, although in this division, the ‘take it easy, old boy, we need you’ letter from Sir Frank Packer claims a chummy equality.

How does one address a prime minister? ‘Dear Sir’ is the simplest way, but ‘Honourable Sir’ and ‘Highly Respected Sir’ appear in Lyons’s list of what he calls the ‘remote greetings’. Some writers press the wrong button, as did the Indian collector of stamps who asked for a gift from ‘Your Majesty’. After Menzies was knighted in 1963, ‘Dear Sir Robert’ became the most popular form. In signing off, some correspondents reminded Menzies of their cause or plight. As well as the ‘obedient servant’ option, there was the religious note, as in ‘Yours devotedly in God’s vineyard’. Some sign off in anger or disgust. A patriotic flourish – ‘For God, the Queen and Sanity’ – assumes that Menzies shares the writer’s crusading spirit.

Some letters were accompanied by gifts. A pair of elephant tusks came as a token of esteem from a South African admirer. A centenarian sent a piece of her birthday cake. A nun sent a ‘miraculous medal’. There were Christmas cards and birthday cards for Menzies and his family. The prime minister was urged to drop in for tea.

Not all the correspondents were so pleased with their prime minister. Lyons finds a group with more demands than congratulations. Their shared belief is that ‘if you want something done, go to the top’. Complaints about bureaucratic red tape are expressed in peremptory tones. If a government official has blundered, it is Menzies’ job to sort things out. It’s his job to see that the old age pension is increased to meet the cost of living. For some, Menzies appears as indifferent and neglectful. Others rely on his ‘safe pair of hands’ and expect those hands to get busy.

It is impossible to read Dear Prime Minister without lamenting the fading of the letter as a form. Fax, texts, and emails may reveal something of the relationship between sender and recipient, but they cannot match the individuality of ink and paper and the feel of the handmade item. In describing the letters to Menzies as physical objects, Lyons makes their ordinariness expressive.

The intent of the letter is usually plain from the start. ‘Please don’t think I’m a crackpot’ is one way to deflect a quick dismissal. Many insist on being ordinary people, undeserving of the great man’s time. Housewives, self-styled, often stress their humble status.

The mood quickens in the later chapters, in which questions of religious and political beliefs appear. Menzies is identified with loyalty to the queen and a Commonwealth which many preferred to remain white. Indian prime minister Jawaharlal Nehru is regularly accused of treachery because of his support for anti-colonial independence movements. And, of course, because he wasn’t white.

Menzies’ devotion to Queen Elizabeth II was so well known that monarchists felt free to criticise her gently, as if from inside the family. ‘Much as I admire and love our dear little Queen, I think she needs a spanking,’ one monarchist wrote. The issue here was the queen’s decision to cancel an allowance made to her uncle, the former Edward VIII. Once a king, always a king.

Ideas about war, communism, the Catholic Church, and the White Australia policy predominate in the late 1950s. Menzies is expected to keep the nation safe from alien powers and to preserve peace and calm at home. His habitual formality of manner was sometimes seen to lapse. He was rebuked for rudeness to Australian Labor Party leader Herbert Evatt in the fractious 1950s, but most often he is praised as an uncompromising enemy of the left. His correspondents show very little interest in Indigenous affairs. Some letters are critical of apartheid and urge a more open approach to immigration. On the whole, Lyons concludes, ‘the majority uphold the fading dreams of white supremacy and imperial solidarity’.

The ‘Paranoid letters’ group might not seem to deserve inclusion, except for the fact that we are still hearing voices like these. ‘Woe to the Bloody City. It is all full of Lies and Robbery,’ writes one of Menzies’ correspondents. Another believed that the Freemasons had ‘telepathic radio sets’ that were controlling the thoughts of influential people like the queen.

Lyons uses the Menzies mailbox to illuminate a period and its problems. Menzies himself plays a minor, mostly passive, role, noting, thanking, but rarely engaging with the issues raised. When a Melbourne journalist indicted the capitalist system for ‘making a hell of this earthly paradise’, he pencilled a note: ‘Do not answer.’

Lyons doesn’t include complete letters and, judging from the extracts quoted, that was a wise decision. His analyses are shrewd and witty. ‘The silent masses,’ he concludes, ‘turn out not to be so silent after all.’ The letters express pain and anxiety; they release feelings of anger and frustration. Although many of the letters are repetitive and clumsily expressed, they offer a rare insight into the concerns of those who thought it worthwhile to write ‘Dear Prime Minister’.

Comments powered by CComment