- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Diaries

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: The love problem

- Article Subtitle: Helen Garner and the fissures between fact and fiction

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

The first two volumes of Helen Garner’s diaries – Yellow Notebook (2019) and One Day I’ll Remember This (2020) – cover eight years apiece. This one covers three. It is an intense, even claustrophobic story of the breakup of a marriage – a story told in the incidental, fragmentary form of a diary.

- Article Hero Image (920px wide):

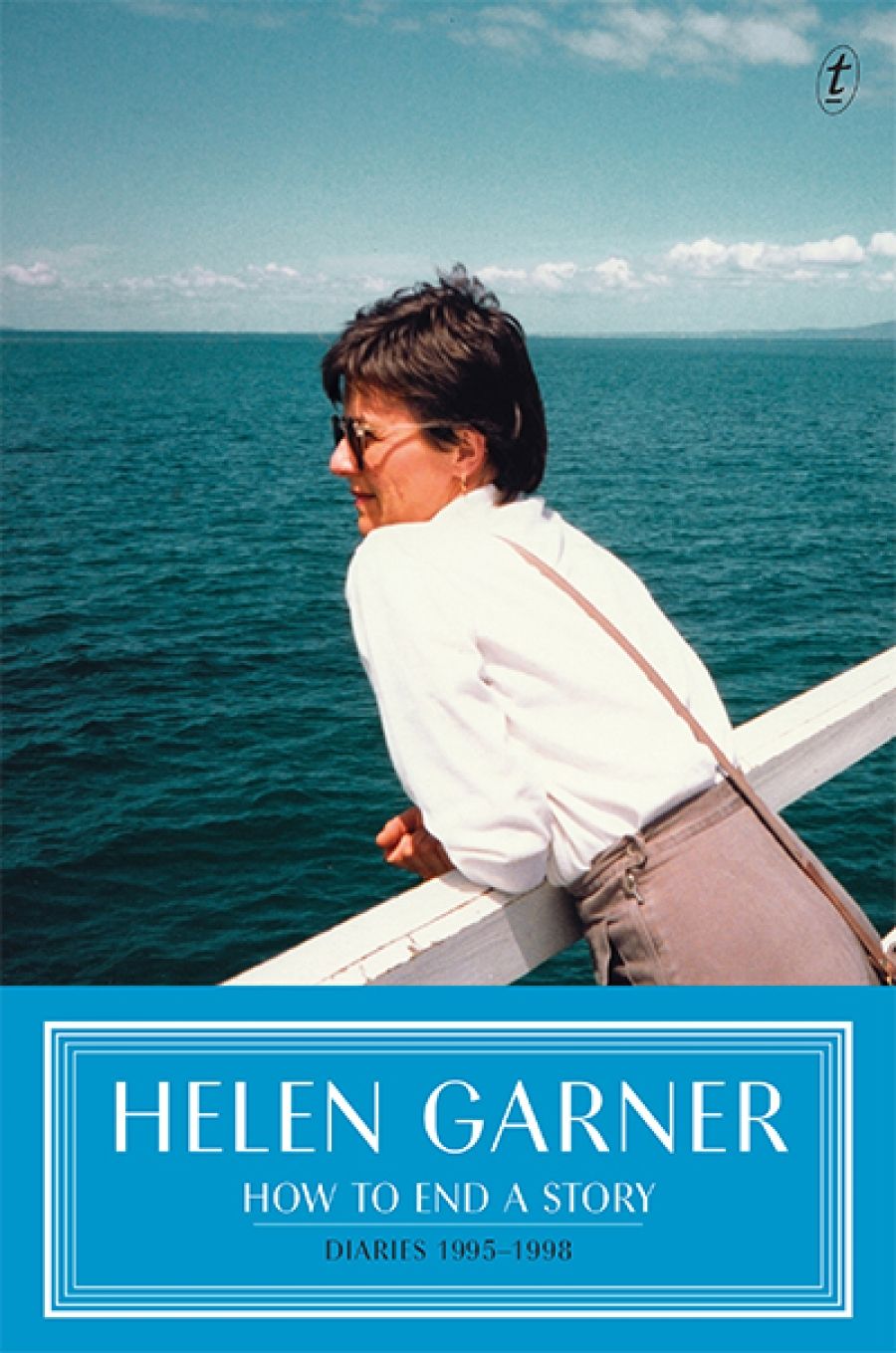

- Article Hero Image Caption: Helen Garner (original photograph by Darren James/Text Publishing)

- Alt Tag (Article Hero Image): Helen Garner (original photograph by Darren James/Text Publishing)

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Lisa Gorton reviews 'How to End a Story: Diaries 1995–1998' by Helen Garner

- Book 1 Title: How to End a Story

- Book 1 Subtitle: Diaries 1995–1998

- Book 1 Biblio: Text Publishing, $29.99 hb, 248 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/b35y6B

In a conversation with Bernadette Brennan, Garner set out a rule for publishing her diaries: ‘all I’m going to give myself permission to do is to cut, and fillet, and chop out bits’ (A Writing Life: Helen Garner and her work, 2017). These entries are selected (cut, filleted, chopped out) with an eye for what it is to break with someone after years. In its obsessiveness, How to End a Story captures how the single self has to be extricated painfully, piece by piece, from shared habits, friendships, places, stories, memories, things.

V is an almost comical figure here, falling somewhere between Casaubon in Middlemarch and Robert in The Diary of a Provincial Lady.

V says that women’s writing ‘lacks an overarching philosophy’ …

‘Bloody fussy women,’ he says.

‘Stupid, cliché-ridden, impertinent, presumptuous, offensive women.’

‘I’m like an ocean liner,’ he says, ‘levelly forging along. And you’re a smaller boat that swerves and flitters here and there – a bright little thing.’

‘I know this mightn’t sound very good,’ he said, ‘but why do you imagine that anyone would be interested in reading your diary?’

This characterisation of V makes How to End a Story about something more than the question of one particular marriage. It becomes a different question: what compels a woman to stay with a man such as this? She herself comes to see the relationship in terms of a ‘classic position’: ‘I think I am in the classic position of a woman artist who in order to maintain a marriage is obliged to trim herself so as not to make her husband feel – what?’

Reading this diary you can sense, in its background, foundational works of feminist writing. About jealousy, and trying to live with it: Simone de Beauvoir’s novel She Came to Stay. About the search for her own living space: Virginia Woolf’s A Room of One’s Own. About accommodating a sexist man: Simone de Beauvoir’s The Second Sex. Beauvoir wrote: ‘The oppressor would not be so strong if he did not have accomplices among the oppressed’. H writes, ‘I wanted so much to be loved that I tried to turn myself into the sort of woman I thought I would have to be … I connived, I enabled, and I allowed him to set hard into worse versions of the misogyny he already felt.’ It is as though H requires herself to test the truths of this long tradition against her own nerve ends.

In 2009, says Brennan, Garner ‘read an ABR review by Vivien Gaston of two books by artists’ wives’. In her journal she wrote: ‘A slightly sickened sense of recognition slithers through me: the serving, the self-abasement or at least – abnegation, the attempts to rationalise the man’s egotistical demands & serene sense of entitlement & the wife’s subservience to these …’

But she had guessed it from the first. ‘Dread: he too will turn out to be manly in that way – looked after by a woman, no longer alive to her yet still drawing full benefits from her … Is there hope for women and men?’

The first two volumes of Garner’s diaries offer, as one of their chief pleasures, the feeling of time as it passes. They are full of small occasions, glancing insights, a slowly accumulating drift of actions and consequences. This one is different. This one is as compelling as a detective story. This one is edited with the sense of an ending.

One of the pleasures of detective stories is how they transform all their incidental detail into what might be evidence. In How to End a Story, H is asking herself questions that have the same sort of effect. Is he having an affair? Should she stay with this man? Or move out, get a room of her own? The reader, questions in mind, starts looking for evidence. The reader is privy to intimate details. The reader is watching for clues. The reader can see what’s coming. The reader can judge.

How to End a Story is alive with the sort of daily events and details that are companionable in writing. Always, there is the straightforward pleasure of Garner’s prose. But this diary’s sense of an ending changes the way in which it’s read. For one thing, it gives symbolic force to certain ordinary things. Her shopping bags, for instance. H’s husband V, being a male genius, needs H out of the apartment all day. She goes to her rented office. She returns, weighed down with bags, to cook the dinner. Alain Badiou, writing on Samuel Beckett, defines four figures ‘generic of everything that can happen to a member of human kind’. The first is, ‘to wander in the dark with a bag’ (Figures of Subjective Destiny: On Samuel Beckett, 2008). It is a diary: these were real shopping bags. Still, for a reader, these shopping bags come to signify what H has to lug about, bring back to the place, empty out to make into something nurturing. Badiou: ‘The two figures of solitude are: to wander in the dark with one’s bag and to be immobile because one has been abandoned.’ The memory of these shopping bags gives extra charge to the shopping bag that V stores, at the end, in his workroom for ‘X, the painter’.

There are symbols in writing because there are symbols in life. These are two writers, breaking up. It makes sense, then, that the facts which have symbolic force in this record of their breakup find symbolic expression in literature. As in Edgar Allan Poe’s story ‘The Purloined Letter’, much depends upon a letter hiding in plain sight. Later, a blue straw Armani hat becomes the fetish object of H’s magnificent rage. In A Writing Life, Brennan notes how, after the breakup, in a room of her own, Garner wrote a twelve-page narrative poem in rhyming couplets called ‘The Hat in the Flat’.

In How to End a Story, H writes about her experience of therapy – and this, too, brings in questions about how symbols work in life. The therapist sits behind H’s shoulder, where she can’t be seen. ‘She said that I’m in competition with her, interpreting my own dreams.’ The therapist translates symbols. ‘“I think,” she said, “that the house is you. The dark part of yourself.”’ But, that dark is metaphorical. The body and the self and its symbols can hardly be separated. There are a lot of dreams in How to End a Story – as though, in recording these, Garner is again worrying at the question of how dreams and symbols and fiction work in with ongoing life. H quotes Don DeLillo: ‘We stand around, look out the window, walk down the hall, come back to the page, and in those intervals, something subterranean is forming, a literal dream.’ Except, it seems, that Garner doesn’t want the dream on its own, self-enclosed and self-sufficient. She wants to include the ground on which that literal dream was formed: the standing around, the looking out the window, the walking down the hall, the coming back to the page.

How to End a Story is working at what Garner calls ‘the crossover between fiction and an account of what happened’. Truman Capote, in an interview published in Conversations with Capote by Lawrence Grobel in 1985, foresaw the ‘conjunction’ of fiction and non-fiction:

I think the two things are coming into conjunction like two great rivers …

Fiction and nonfiction?

Yes. They’re coming into a conjunction, divided by an island that is getting more and more narrow. The two rivers are going to suddenly flow together once and for all and forever. You see it more and more in writing …

Do you think that Joyce and Proust took writing as far as it could go?

Oh no, I don’t at all. There is a root for fiction, but I think it’s going to have to involve more and more what it is that I’m trying to do, which is to make truth into fiction, or fiction into truth – I don’t know what it is …

(Capote kept a journal, too. He said: ‘I do dialogue and description. In my journal I have my special list of truly despicable people. It’s run now to something over four thousand names.’)

Truth into fiction, or fiction into truth – H says, ‘maybe my right place to work is down a fissure between fiction and whatever the other thing is. Down a crack.’ Because How to End a Story is a diary, in telling its story it tries to discover how stories take shape in day-by-day life, through the weird interplay of accidents and habits and happenings and revelations and, sometimes, decisions. ‘About writing,’ she wrote: ‘meaning is in the smallest event. It doesn’t have to be put there: only revealed.’ Along with this interplay between dreams and daily life, the diary format offers Garner a way to make the story work through fragments. She dispenses with all the machinery of getting characters up and dressed and breakfasted and out the door, and from one country to another, and from one year to the next. She keeps only those events that reveal their meaning.

How to End a Story is composed with something like a novel’s sense of an ending. But, that is not to say that it doesn’t matter whether it is fiction or ‘whatever the other thing is’. Because this is a diary, because it is true, it concentrates attention on the writer’s particular way of seeing people and places and things. We can contest all of it.

At times, reading this diary, you feel like a spy. At times you feel like a friend. At times you feel like a judge. Take the occasion when H tells someone to get fucked in a restaurant. She gets ticked off for that. The reader can judge V, and the other people there, and her. Meanwhile, H is judging him, and them, and herself too. Reading some diaries (Elizabeth Bishop’s translation of Helena Morley’s diary, for instance) is like sitting where H’s therapist sits, looking over the writer’s shoulder. Reading Garner’s diaries is not like that. It is much more like talking face to face. At one point, H twists around to see her therapist – to check that she is there.

In the first volume, H writes, ‘I see that what I am doing, in this diary, is conducting an argument with myself.’ That argument makes a place for the reader. In the second volume of these diaries, H is reading Peter Handke’s notebooks, The Weight of the World. She writes: ‘He’s more brutal with himself than I have ever been. He inspires me to try to be more truthful in this book. It’s hard, for I am always hiding something, either from myself or from the person who may or may not, today or on some future day, read this and be inclined to think less of me.’ That is, the reader was there all along: imagined counterpart; spy, friend, judge; someone with a place held for them in that ongoing argument which the writing is.

At the end of his love poem ‘They Flee From Me’, Thomas Wyatt suddenly turns the poem over to the court of public opinion: ‘But since that I so kindly am served / I would fain know what she hath deserved.’ The last line reveals that the judges have been gathered around the poem, listening, from the first. Perhaps for Garner that’s the point of mixing fiction with ‘whatever the other thing is’: it makes the reader part of it; it gives the reader licence to judge. Garner remarks that her story of The First Stone is ‘full of holes’, for instance. She seems surprised that readers expected anything else.

This is what connects Garner’s diary project with her sequence of books about legal trials: an interest in the meeting of opposing views; a structure which looks for justice out of conflict. I thought of Garner’s diary when I read Annie Ernaux’s brilliant memoir A Girl’s Story (2016):

I needed them to be alive, as if I needed to be writing about what is alive, to be endangered in the way one is when writing about the living and not in the state of tranquillity that prevails when people die and are consigned to the immateriality of fictional characters. There is a need to make writing an untenable enterprise, to atone for its power (not its ease, no one feels less ease in writing than me) out of an imaginary terror of consequences …

Garner, too, seems to pay for the right to speak by endangering herself, to an extent that’s disconcerting.

‘Don’t talk to anyone about this, will you.’ Normally this would enrage me, but I say, ‘I won’t. I’m too ashamed. I’m ashamed of my own naivety. I’m ashamed for you. And I’m ashamed because people will say, “What? She’s still hanging around waiting for that jerk-off?” I’m not going to tell anybody about this.’

And I’m not …

But she does. Because she needs to be ‘writing about what is alive’, to be endangered – and because, answering those reiterations of shame, she takes an epigraph from Jung: ‘The love problem is part of mankind’s heavy toll of suffering, and nobody should be ashamed of having to pay his tribute.’

Comments powered by CComment