- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Art

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Clear Head Clear Vision

- Article Subtitle: A thematic look at the textile designer Frances Burke

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Frances Burke (1904–94) was the leading textile designer in Melbourne from the 1940s to the 1960s. Her modernist furnishing fabrics, preferred by architects, interior designers, department stores, and homemakers, were popular in domestic and commercial interiors, and her reputation was national. Her design skills were complemented by a good head for business and her command of all aspects of production, distribution, and marketing. The distinctive style of her textile designs is neatly summarised by the authors of this splendid volume: ‘ A single, bright colour and clean, simple linework printed on quality cotton or linen made Frances Burke’s designs modern in style, instantly identifiable and very appealing.’ Burke’s wide-ranging design sources included flora and fauna, indigenous and exotic themes, as illustrated in a selection of her titles: Canna Leaf, Tiger Lily, Seapiece, Totem, Rangga, Pacifica and Moresque.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Christopher Menz reviews 'Frances Burke: Designer of modern textiles' by Nanette Carter and Robyn Oswald-Jacobs

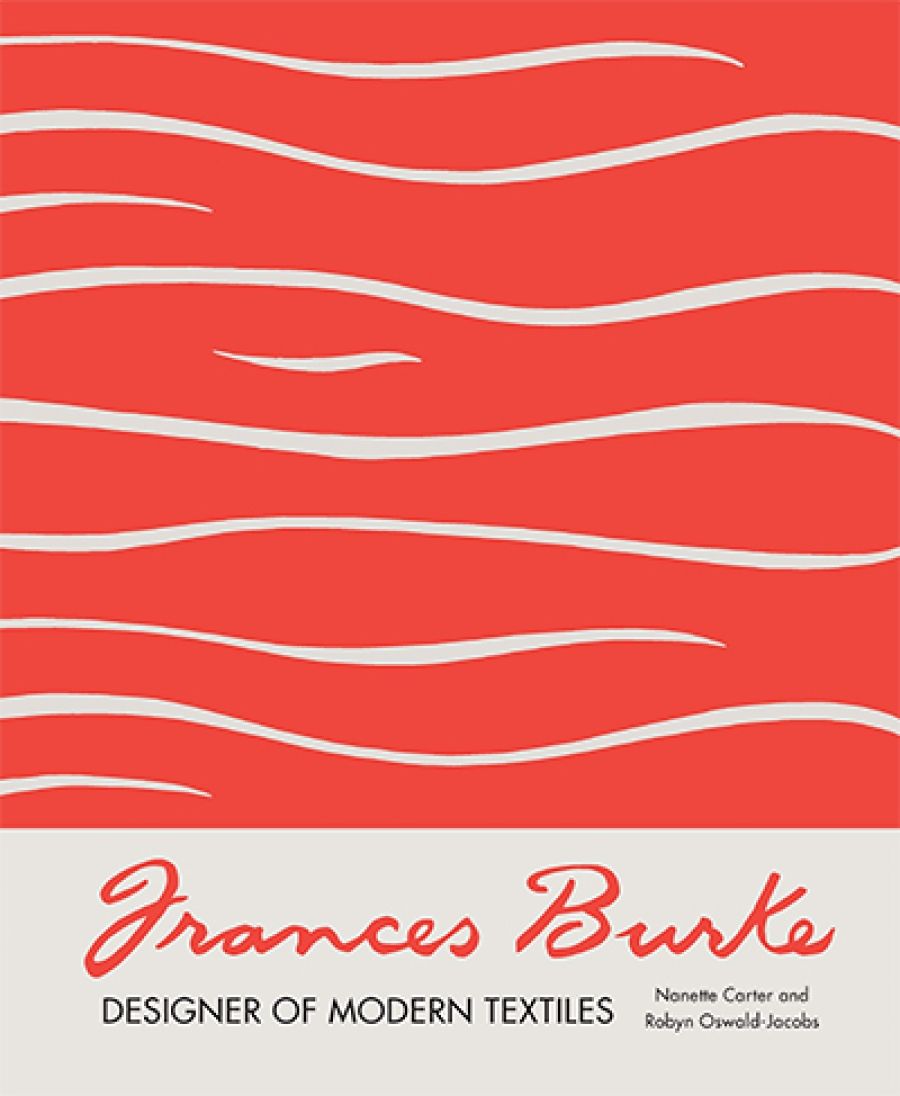

- Book 1 Title: Frances Burke

- Book 1 Subtitle: Designer of modern textiles

- Book 1 Biblio: Miegunyah Press, $69.99 hb, 231 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/oeoybm

Burke was born in Melbourne into the rag trade: her father was a tailor’s presser, her mother a former tailoress. This gave Burke an early appreciation of textiles. After first training as a nurse, she retrained as an artist in the 1930s, enrolling at the Gallery School, Melbourne Technical College, and the George Bell School. Her first textile designs were produced in 1937, the year she registered her business. She was soon supplying designs to Georges and the Myer Emporium. By 1941, her work was sold through David Jones in Sydney, followed by shops in Perth and Adelaide and many regional centres. To ensure quality and viability, Burke managed and oversaw the design and production and wholesale and retail aspects of the business.

Burke’s career as a designer was not all plain sailing; her early attempts at textile production were not immediately successful. With her steely determination she soon solved any technical problems and was on the path to success. Indicative of her ambition is her private note ‘Two Year Plan for Living’, probably written in early 1937: ‘Clear Head Clear Vision / Clear discrimination that I shall not waste my time on inessentials.’ As one of her friends noted, Burke did not ‘suffer fools gladly but she mellowed’.

Nanette Carter and Robyn Oswald-Jacobs’s narrative of Burke’s life and achievements is part biographical – charting the designer’s life with her partner, Fabie Chamberlin, and her career and influence – and part thematic, led by her professional work. The designs are analysed, major and minor projects discussed, and technical information is imparted with a light touch. The authors provide context for both Burke’s development as a designer and for the artistic milieu in which she operated. We also get a strong sense of the rich design culture in Melbourne from the 1930s onwards, in which Burke was a central player.

From the late 1940s, Burke began visiting America. This kept her abreast of international design trends, which she promoted avidly back home. Her retail shop, New Design in Melbourne’s Hardware Lane, displayed furniture by Melbourne designers Grant Featherston and Clement Meadmore, as well as American imports. She collaborated with leading Australian architects, including Roy Grounds and Guilford Bell, to supply designs for their architectural projects. One of the larger ones was for the Ansett Hayman Island Resort (1949). In addition to domestic and resort interiors, her fabrics appeared in hospitals, offices, universities, and libraries. One of her final designs was Black Opal for the proscenium curtain in the Canberra Civic Centre Theatre, which opened in 1965.

Rangga, 1941, Frances Burke (photograph supplied, © RMIT University)

Rangga, 1941, Frances Burke (photograph supplied, © RMIT University)

Although Burke was primarily a designer of furnishing fabrics, wartime shortages and the sheer appeal of her designs meant that they were commandeered for clothing. In the 1950s Zara Holt sold garments made up in Burke’s patterns at her boutique, Magg in Toorak. In London, in 1957, Mary Quant had a hot pink blouse produced in Burke’s Goanna design.

Burke’s business and its promotion were aided by her friendships with influential patrons. Foremost was Maie Casey, a devotee of Burke’s. From 1940 to the 1960s, she used Burke’s designs in the Caseys’ private plane, at the Washington residence when her husband became ambassador, in a suit made of Bengal Tiger when she was vicereine of Bengal, and in Yarralumla, when Lord Casey became governor-general. Correspondence from Maie Casey to Burke is reproduced in the book, giving an immediate sense of the commissioning process and the close friendship between the two women.

Frances Burke, an important figure in Australian design, is well represented in the major public collections in Australia, notably the National Gallery of Australia, the National Gallery of Victoria, the Powerhouse Museum, and the RMIT Design Archives. Her work has been featured in many exhibitions and is regularly displayed. Still, she deserves to be better known. In this first monograph, she has been well served by the authors and publisher. Carter and Oswald-Jacobs bring decades of detailed research. The superb book design is by Daniel New, and in addition to the many illustrations of Burke’s own work there is a great selection of historical photographs. Frances Burke: Designer of modern textiles forms a substantial addition to the literature on twentieth-century Australian design.

Comments powered by CComment