- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Memoir

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Glittery routes

- Article Subtitle: An unavoidable bus route in Paris

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

The closest I have ever come to expiring from heat exhaustion was not during one of Melbourne’s oppressive summers. It was not in north-east Victoria as bushfire smoke choked the air and even the kangaroos abandoned the grasslands. The closest I have ever come was not even on the continent of Australia. It was on the number 26 bus as it crawled up the Rue des Pyrénées on a sweltering June day in Paris.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Megan Clement reviews 'No. 91/92: A Parisian bus diary' by Lauren Elkin

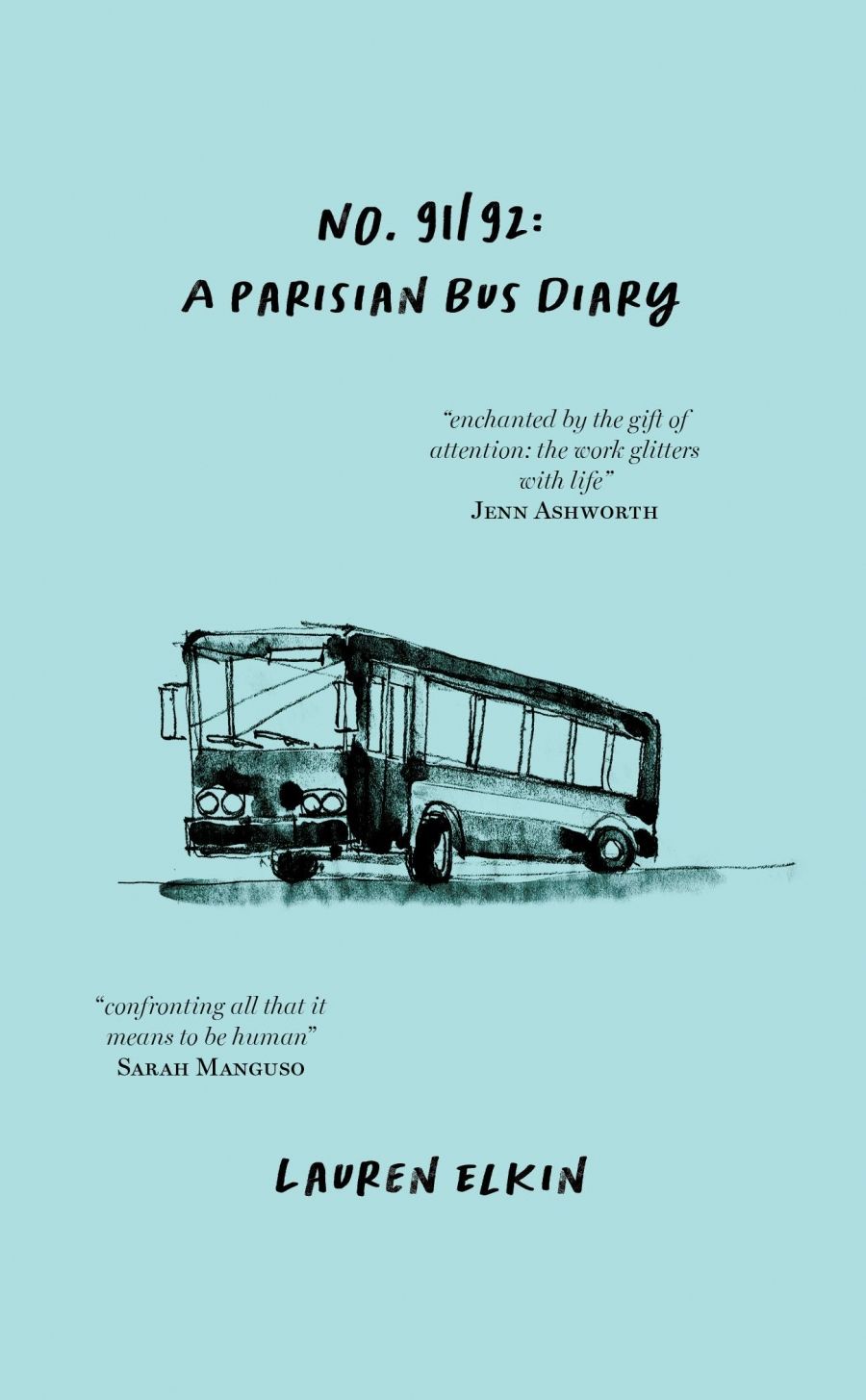

- Book 1 Title: No. 91/92

- Book 1 Subtitle: A Parisian bus diary

- Book 1 Biblio: Tablo Tales, $22.99 hb, 128 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/MXyyZN

All the life of a Paris bus is present in No. 91/92: A Parisian bus diary by Franco-American writer Lauren Elkin, who also recently translated Simone de Beauvoir’s newly published ‘lost novel’, The Inseparables. A series of diary entries composed on her iPhone as Elkin commuted to her teaching job twice a week in 2014 and 2015, No. 91/92 chronicles city life as seen through a steamed-up window.

Elkin is a wry observer, a witty companion on an undeniably Parisian journey. While waiting for her citizenship application to be approved, she thrills, as many of us would, at ‘having been mistaken for a French girl who might know anything about scarves’ when a fellow passenger seeks her sartorial advice. (Try as I might to resist Paris clichés, it is a simple fact of life that the city’s men and women are in on some secret about the tying of scarves that has passed the rest of the world by.) On a Thursday afternoon in October, ‘a man in a hat looks out the window and says “sarkozy”’.

At the same time, Elkin could also be any of us, anywhere, dragging ourselves to work earlier than we’d like to, ‘blood still heavy from sleep’. Here in these notes are the manspreaders, the noisy Americans, a texting nun, the tired mothers with children who want to lick the walls. Here are the eccentrics – ‘It’s 8.30am and there is a woman in business attire crunking on the bus.’ And here is our delicious, silent judgement of fellow passengers: ‘Thursday morning / Your glittery sandals are awful but the rest of your outfit is good.’

In my first year in Paris, I too picked up the 91 bus at Elkin’s stop of Port-Royal Berthollet and rode it to the Gare de Montparnasse. I too rolled my eyes at the endless 21s that whooshed past before the 91 finally arrived (‘My hero’). Presumably like any other 91 traveller who reads this book, I wait patiently for the arrival of a man ‘so smelly I had to stand back up’. He duly arrives on page 63 (and again on page 89).

Like Elkin, I also rode that bus in the aftermath of horrifying terrorist violence; in her case the 2015 Charlie Hebdo attack, in mine the massacre at the Bataclan just months later. When she begins her bus diary in 2014, she promises to keep ‘a public transport vigil’. This idea of a vigil changes meaning in the days after the attack when, she notes, ‘I keep crying on buses.’ We all did. An event like this, Elkin writes, ‘casts daily life in a dangerous hue, when you thought you were just going about your business’.

No. 91/92 explicitly takes its cue from Georges Perec’s An Attempt at Exhausting a Place in Paris (1974), in which he tries to record everything he sees from his table at a café on the Place Saint-Sulpice. But it also echoes Elkin’s previous book, Flâneuse (2016), a cultural history of women who walk in cities from Paris to London, Tokyo to New York. In Flâneuse, Elkin interweaves her own experiences of urban walking with those of Jean Rhys, Georges Sand, Virginia Woolf and others who went before her. Literary ghosts are still present in No. 91/92, but here they follow Elkin as she traverses the city, not the other way around.

No. 91/92 is often more effective in achieving what Elkin sought to do more explicitly with Flâneuse: track the way women move through a city, observing it, being shaped by it, praising it, cursing it, exhausting it. During its course she gets pregnant, and in her elaborate dances for seats, her growing revulsion at the manifold scents of Paris and her fellow passengers, her fatigue as she rides for a single stop to save energy, we see that the act of commuting, just like that of walking, is inescapably gendered. Her pregnancy turns out to be ectopic – ‘that’s greek for what the fuck’ – and we also follow her, still on the bus, as she deals with the loss, recovers from her surgery, avoids her students’ questions about where she’s been.

It’s devastating to read, but it also forms part of Elkin’s wider point: when we ride the bus, we do not know if the person opposite us has lost their pregnancy, has had Covid, was at the Bataclan. We do not know if they are playing Candy Crush on their phone, texting their mother, or writing an experimental diary about riding the bus. And yet we ride side by side, together and apart, sometimes cursing public transport but still going where we need to go. ‘I believe this is called community,’ Elkin writes.

Comments powered by CComment