- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Essay Collection

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Apocalypse now

- Article Subtitle: Delia Falconer’s new essay collection on climate and culture

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Reading Richard Flanagan’s searing allegory The Living Sea of Waking Dreams (2020) and Delia Falconer’s new non-fiction book, Signs and Wonders: Dispatches from a time of beauty and loss, in rapid succession was a surreal, slightly unmooring experience. Both authors lucidly capture the dreamlike state of disbelief and horrified fury with which we’ve watched the world slide terribly into the 2020s. Both are part of an outpouring of new language, new stories, new ways of expressing our reactions to the barely imaginable scale of realities we can no longer ignore: fire columns that remind NASA of dragons; a pandemic that conjures news scenes we had thought the province of cinema. As our poor human cognition struggles to catch up, scientists become poets, novelists become scientists.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Jonica Newby reviews 'Signs and Wonders: Dispatches from a time of beauty and loss' by Delia Falconer

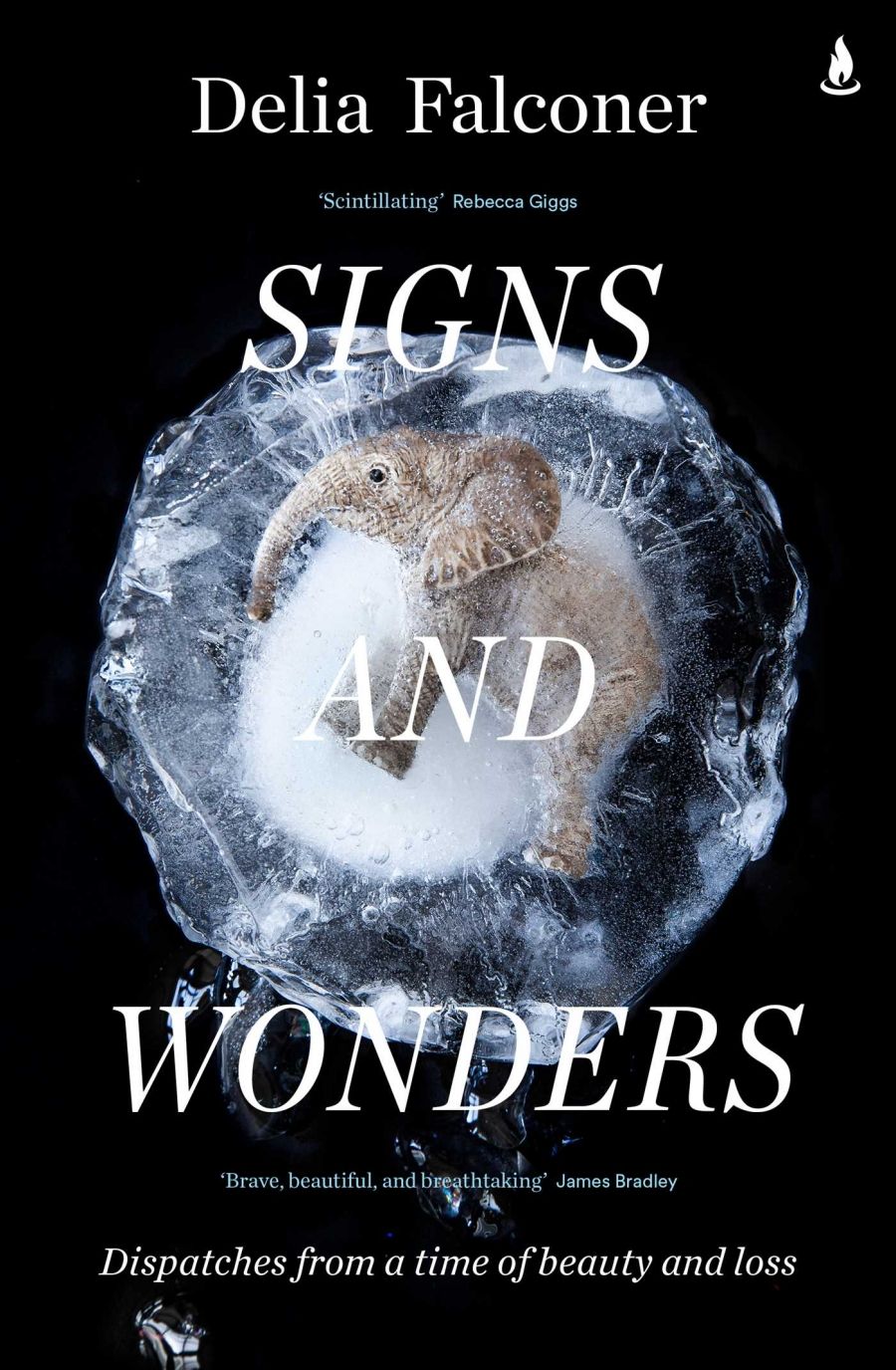

- Book 1 Title: Signs and Wonders

- Book 1 Subtitle: Dispatches from a time of beauty and loss

- Book 1 Biblio: Scribner, $32.99 pb, 290 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/NK44ZO

It seems as though language and culture are reaching a phase shift, a tipping point, and it’s this head-spinning transition that novelist and essayist Delia Falconer vividly charts in her exquisite new collection of essays. In the opening essays, Falconer shares how diametrically her own view of the world has tilted. Where once she would scan the empty waters of Woolloomooloo for fish and assume seasonal variation, now she wonders if the fish have all gone. Where once a swim in a lovely bay was a simple joy, now thoughts veer to how high the water will rise when the ice caps melt. ‘Is it true the world’s going to die soon?’ asks her young daughter. Falconer struggles for a convincing answer.

What Falconer captures so movingly is the queasy vertigo many of us are experiencing as we contemplate how much the world has changed, or how much our perception of it has – newly charged with portent, with intimations of disaster, and yet almost unbearably beautiful, as if the prospect of unfathomable loss has imbued everything with wonder and meaning and intent; ‘as if,’ Falconer reflects in the titular essay, ‘we’re entering a new era of signs and wonders’.

And what wonders. An exquisitely preserved prehistoric wolf cub released by thawing permafrost. The footprints of vanished Roman villas revealed by unprecedented drought. Falconer explores the emotional complexity with which we receive these images – should we be beguiled, horrified, or both? Is this abundance of beauty like the epicormic growth that spurts desperately from a burnt tree? The fireworks ‘unleashing its biggest rockets and most glittering cascades in its final moments’? Are they signs of a dying earth?

Alongside are the sudden, bewildering losses: sixty per cent of endangered Saiga antelope found dead in a single spring ‘as if a switch had been turned on’. Formerly billion-strong clouds of Bogong moths completely gone by the summer of 2018. This eerie listing of disappearances recalls the abrupt disappearance of limbs and people that characterises Flanagan’s allegorical cri de cœur; both writers beautifully portraying an oscillation between anguish and dissociated numbness.

For Falconer, her permanently altered world view feels like a rebirth of animism – to the deep notion that the world is alive and has agency (how did we teach ourselves otherwise?). If it does, it is screaming in pain, in one case literally. One of the more vivid images is of scientists observing that ‘icebergs are melting more loudly and emitting “excruciating” sounds’, while the lead author of another phonic study of ice-melt laments ‘These … are the songs of a changing climate.’ Even scientific culture is shifting – the colourless language of craft no longer seems adequate to the task.

From reflections on feeding birds, analyses of literary trends, to Falconer’s Covid and fire diaries, the essays are complex, ambitious, rewarding. Personal vignettes ground the reader with recognition (‘Yep, been there – I’ve thought that too …’) while providing scaffolding for a cornucopia of intellectual treasures: unexpected facts, insightful connections (why do we love vampire films?), philosophy, fairy tale and myth. It kept me turning the pages, looking for ‘wonders’, enjoying the next hit – a friend who thinks her house is haunted because it keeps manifesting lumps of coal, a writer who suggests that many ghost sightings were hallucinations caused by coal-gas fires. Thus the difficult, the unpalatable, is absorbed.

These examples are from ‘Coal: An unnatural history’, a standout chapter for me. It’s a well-travelled topic, but Falconer’s take is fresh. On a family trip to Parliament House in Canberra, her children are invited to look for ‘Shawn the Prawn’, an ancient creature embedded in the handsome black limestone of the grand Marble Foyer, which, we soon learn, owes its black colour to carbon. From there, we launch into a rollicking retelling of Australian history through coal. Did you know that the first European ship to reach the east coast was originally a merchant collier, or that the Awabakal people of the Hunter region used coal to waterproof canoes? A quote from a 1913 article by Australian writer Mabel Forrest made me laugh in wry recognition: ‘A woman’s life … is like the earth that stores the coal, all its accumulated years of love and tenderness fuel for a man’s brief burning hour of passion.’

Many of the book’s recurrent themes are expressed here. Deep time – reminding us of the mind-bending aeons it took to create the ‘products’ we so swiftly consume. The bitter-sweet uneasiness of raising children now. Without giving too much away, there’s a shock reveal – Shawn the Prawn is not who we think he is – highlighting the symbolism of lying to children in the very halls of power; the site, as we are reminded chillingly, of a federal minister, a future prime minister, holding up a lump of coal and saying, ‘Don’t be afraid.’

Glamour, in the sense of an old faery spell or enchantment that prevents us seeing what’s really there, is another recurring theme, explicitly so in ‘The Opposite of Glamour’, where the dizzy enchantment of social media, the fetishising of ever-faster consumption, the parallel narrative of infinite abundance, blind so many of us to the unspeakable costs of our sparkling lifestyles – a Mordor of indentured slaves, a collapsing natural world. The potentially fatal nature of this bewitchment is expressed most mordantly in the final essay, ‘Everything Is Illuminated’, in which Falconer points out that the uncanny, phosphorescent beauty of Luminol, used to solve murders in the popular television program CSI, literally casts a glowing glamour over death.

Early in 2020, I drove through coal-stricken forests to visit my mother in Mallacoota. On the way, mindful of not exacerbating anyone’s trauma in that fire-massacred town, I called my friend, disaster psychologist Dr Rob Gordon, for advice. He said, ‘One definition of trauma is that it irreversibly shatters an assumption about the world we didn’t know we had.’

On reflection, that’s what we’re all going through now. The last four years feel to me like a mountainous cognitive shift, with a big pointy summit-spike on the eve of 2020, when, as if in a prophesy, our summery beaches turned apocalypse red, before a pandemic sealed the sense that the world will never be as it was. Our changing climate is changing us. Our language, our culture, our imaginations are adjusting as our poor brains struggle with ‘irreversibly shattered assumptions about the world we didn’t know we had’.

Delia Falconer’s mesmerising Signs and Wonders helps us to process the disorienting complexity of living in this time of great beauty and loss.

Comments powered by CComment