- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Essay

- Custom Article Title: Max Dupain’s dilemmas

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Max Dupain’s dilemmas

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Max Dupain, one of Australia’s most accomplished photographers, was filled with self-doubt. He told us so – repeatedly – in public commentary, especially during the 1980s, in the last years of his life. It is striking how candid he was, how personal, verging on the confessional, and how little attention we paid to what he said, either during his lifetime or since (he died in 1992, aged eighty-one).

- Article Hero Image (920px wide):

%20copy.jpg)

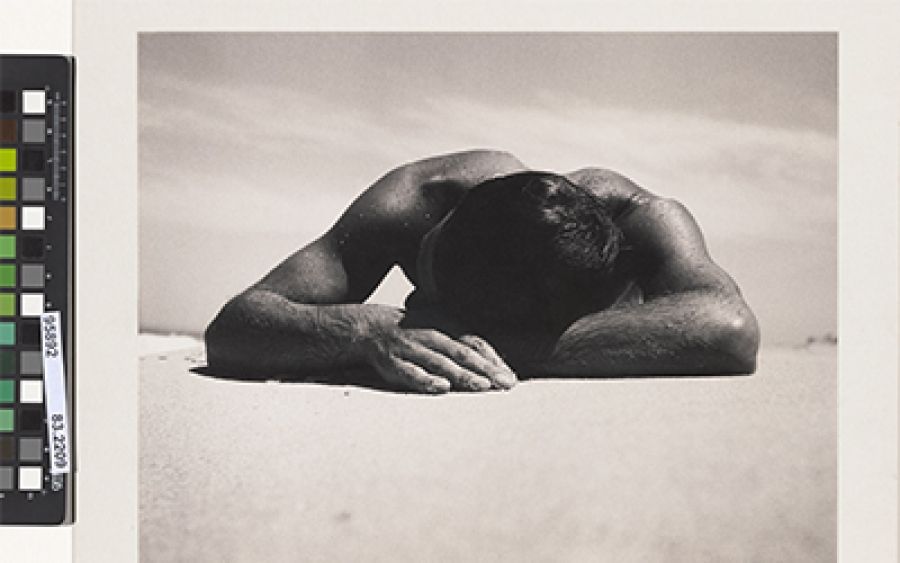

- Article Hero Image Caption: <em>Sunbaker</em>, c.1938 prtd c.1975, by Max Dupain, gelatin silver photograph, National Gallery of Australia, Canberra. Gift of the Philip Morris Arts Grant 1982 1983.2209

- Alt Tag (Article Hero Image): Sunbaker, c.1938 prtd c.1975, by Max Dupain, gelatin silver photograph, National Gallery of Australia, Canberra. Gift of the Philip Morris Arts Grant 1982 1983.2209

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): 'Max Dupain’s dilemmas' by Helen Ennis

There are, of course, many potential ways forward. Rebecca Solnit offers one, writing in The Faraway Nearby that ‘empathy is first of all an act of imagination’. I found this revelatory: it helped me start imagining different kinds of narratives for Dupain and his photography. So, in a different way, did a comment from Jill Crossley who worked at Max Dupain & Associates in Sydney in 1957–58. She loved the convivial and supportive atmosphere created by Dupain and his colleagues, with everyone being encouraged to pursue their personal photographic work on weekends and to present the results for discussion. What Crossley found exceptional was the way the men responded; they openly ‘expressed their feelings’ about the photographs they shared.

Throughout his life, Dupain published commentary on photography, in books, newspapers, and magazines. His début was in 1935 in art patron Sydney Ure Smith’s influential publications The Home and Art in Australia. For decades, Dupain was an articulate, passionate champion of modern photography and developed a strong, distinctive voice, opinionated, but not particularly personal. That began to change after his first retrospective exhibition, which was held at the Australian Centre of Photography in Sydney in 1975. It attracted a great deal of attention, culminating in 1980 in a one-person exhibition at the Art Gallery of New South Wales and publication of a scholarly monograph, the first on a living Australian photographer, written by the Gallery’s first curator of photography, Gael Newton. Dupain provided a living link to the past at a time when the historical consciousness of Australian photography was growing (there had been only one attempt at a history, by Jack Cato in 1955, and two new histories of photography did not appear until 1988, the year of the Bicentenary of the European invasion of Australia). But Dupain was also active in the present; he was a leading architectural photographer, a committed art photographer, and between 1979 and 1985 the photography critic for The Sydney Morning Herald. His profile reached its zenith during the 1980s. As the ‘Grand Old Man of Australian photography’, as writer Craig McGregor called him, he received extensive media coverage and gave numerous interviews. He also wrote his most extended autobiographical essay during this time; it appeared in his book Max Dupain’s Australia in 1986.

In his published and recorded interviews, Dupain told us that he had been ‘full of self-doubt all his life’. He confessed that he didn’t like people, and never had. In 1991, nine months before his death, he explained to McGregor that ‘to go into a room full of strangers is a chore for me … though not as bad as it used to be, because I don’t give a stuff any more’. He publicly questioned the value of his social and professional interactions, saying, ‘I always count the time, and the cost, and I think, Christ, I could be doing better things than this!’ ‘I can effect a relationship,’ he said, ‘but afterwards I think: was it worth it?’ What he did like was ‘to do things … I hate wasting time. That’s why I’ve got so many bloody photos!’ He found travelling ‘nerve wracking’ and after World War II made only three trips overseas, to Fiji in 1955, Bangkok in 1974, and Paris in 1978 (all were for work). In a more intimate vein, he wondered aloud whether he had ‘reciprocated adequately’ in his relationship with his wife and two children and acknowledged Diana’s ‘unremitting tolerance for a husband with such “insufferable single-mindedness” [her words]’.

In the writing of his own story, Dupain identified the war years as a turning point for his life and work. Among the most profoundly destabilising personal events he had to deal with were the unexpected decision of his first wife, Olive Cotton, to leave him in 1941 after eighteen months of marriage, and their ensuing divorce. His friends and colleagues, including his business partner Ernest Hyde, designer Richard Beck, and photographer and filmmaker Damien Parer, were dispersed across the globe, many of them placed in harm’s way. Dupain was devastated when Parer was killed while filming the battle between US and Japanese troops on the island of Peleliu in 1944. Between 1941 and 1945, Dupain, a pacifist, worked as a camouflage officer for the Australian Department of Home Security and was based at different locations in Australia, Papua, and New Guinea, as well as the Pacific. Like so many of his peers, he was deeply affected by the long periods spent away from home, telling journalist Candida Baker decades later, ‘I can’t underscore enough how difficult it was to settle down when I came back.’ In Max Dupain’s Australia, he elaborated further on ‘the long-term shock’ he had experienced:

The unstable war years, the grudging adaptation to ever-changing surroundings, the thousands of impressions both good and bad of varying environments, all added up to long-term shock. I just needed a settled emotional life for a while in order to get my life and work into a new perspective. I did not want to go back to the ‘cosmetic lie’ of fashion photography or advertising illustration …

This is a significant passage, not only because it acknowledges his loss of equilibrium in personal, direct language but also because it foreshadows the typically practical way Dupain dealt with his fraught emotional state. He decided to change direction in his work, turning to architectural photography, which he considered truer to his values and which became a mainstay of his practice from the 1950s onwards. Architecture involved less interaction with people than fashion or portraiture, which he welcomed. Jill Crossley recalled with amusement that Dupain had ‘a strong aversion to some of his clients (they probably talked too much or were boring) and if he thought we could handle them, managed to be out when they arrived’. She concluded that ‘he was a “loner” and needed plenty of space’.

Various other adaptive strategies can be identified. We know, for example, that Dupain was extremely diligent and worried about every assignment he undertook ‘for days beforehand’. He liked to be as well prepared as possible for his photography – creatively, technically, practically. As he explained:

Although I shoot extemporaneously a lot of the time, I prefer to have half a dozen shots in my mind. Probably I have seen them many times under different conditions and have been thinking about them. The moment will come when I shall go to them and make the photographs … I feel the contemplation of the subject brings it closer to you.

Photographer and critic Robert McFarlane regarded his commitment to his work as ‘ferocious … [and] almost painful to watch’, while the architect Harry Seidler, his long-term client and friend, considered ‘his pursuit of perfection’ to be ‘almost maniacal’. This level of intensity and meticulousness was also evident in the development of a practice of physical and psychological confinement, which Dupain outlined in 1991: ‘skittering around the periphery doesn’t interest me one little bit … [I like] to involve myself in, maybe, a small area geographically and work it out, as simple as that’.

We know, too, from Rex Dupain, that his father was ‘a man of habit. He liked system, order … he didn’t like being taken out of his habitual little state of being’. Max’s studio manager Jill White observed that he was ‘nervous about moving out of his comfort zone’. As many of his colleagues and intimates noted, he worked far too much, to the exclusion of a great deal else. Photographer and friend David Moore commented that he didn’t ‘want to be so devoted to the craft that it rules my life, as I think it did with Max’. By Dupain’s own estimate, he made more than a million photographic exposures during his career, a volume of activity he acknowledged as both excessive and a way of coping with self-doubt. He remarked to Craig McGregor: ‘I’ve smothered it [self-doubt] all up by being productive.’

While Dupain was frank about his working method as a way of controlling his self-doubt and anxiety, publicly he offered little insight into their psychological, emotional, or larger societal origins. He claimed, for instance, that he didn’t know why he was ‘devil-driven’, as Diana Dupain described it. He supposed ‘the will to achieve something is at the back of it all, and what’s behind that God only knows’. Perhaps the closest he came to an explanation was the recognition that his behaviour replicated his father George Dupain’s. Max felt that George, who was a pioneer in physical education in Australia and a eugenicist, was the same: ‘He had his work … and he was terribly devoted to it.’

When questioned by McGregor about why he didn’t like people, Max responded, ‘I don’t know’, speculating that ‘it may have something to do with being an only child; my parents were not over-social’, and left it at that. He particularly disliked mixing with groups of photographers, telling Candida Baker in 1988: ‘They talk about film speeds, printing paper, aperture, camera optics. Never do they mention any emotional content, or that they’ve taken a photograph because they were influenced by the “Moonlight Sonata”.’

One of the most heightened instances of Dupain’s anxiety – when he was beset by ‘continual, nagging worries’ – was his so-called ‘Paris experience’. In 1978, Harry Seidler invited him to photograph the Australian Embassy in Paris, which he had designed and which had been completed a few months earlier. The invitation would not have come as a surprise. The two men had already worked together for twenty-five years and had a productive though often testy relationship. Seidler’s wife, Penelope, commented that they ‘always used to bicker a lot … They each complained about the other one being very difficult, but beneath that there was a big respect.’ However, despite Dupain’s French ancestry, love of French photography, interest in the high points of Western art on display in Paris, and the prospect of having the well-travelled, erudite Seidler as a guide around the city, he initially declined the commission. He had no appetite whatsoever for international travel and felt unable to resolve potential technical obstacles: how much film would he need; how would he deal with the unfamiliar European light; how would he process his negatives; what would he do about a darkroom?

After what Rex Dupain remembered as a protracted ‘would he, wouldn’t he debate’ between photographer and architect, Dupain finally relented. The terms are revealing. A 1984 article reported that he ‘packed up his hampers and took his darkroom with him – developing tanks, chemicals, the lot!’ There was so much equipment that Seidler had to obtain special permission from Qantas to transport it. Seidler also resolved the vexed issue of the darkroom facility, arranging to convert a kitchen at the Embassy so that Dupain ‘was able to operate exactly as he did at home’.

Soon after his arrival in Paris, Dupain sent Jill White the first in a series of postcards that underscored his agitated state of mind. ‘Hello – and I don’t say that very cheerfully,’ he began, proceeding with a comment on what he saw as the scale of the task ahead. ‘The Embassy is an enormous building. It frightens me in its detachedness and Germanic efficiency. It’s pure Bauhaus .. . My thoughts are just to get the embassy done and get home. I don’t belong to Paris.’ In the week devoted to photographing the building, Dupain produced a series of dramatic interior and exterior shots that met, if not exceeded, the high expectations of both men and that continue to be widely published and appreciated. As was typical of Dupain’s architectural photography, they celebrate the building’s sculptural forms and are supremely confident and authoritative, but they are also very hermetic. In the absence of environmental context and detail, the viewer is obliged to react to the images rather than find their own pathway into them. While Seidler was, in Dupain’s words, ‘elated’ and ‘smiling’ at the completion of the assignment, Dupain was experiencing a level of exhaustion he had never known before.

Dupain spent the second week of the trip on his own, free to do as he wished. He later admitted that ‘I’ve never been so lonely in my life’. Seidler left him with a list of sites around the city he thought he might like to visit, but Dupain kept up his longstanding practice of confinement, later explaining that he ‘selected a very small part of Paris and worked it over – I didn’t even get to Sacré-Coeur’, the popular tourist site on the right bank of the city. This behaviour astonished Seidler: ‘All he did was explore the walking circumference from our hotel! He never got to Montmartre! He only spent one day in the Louvre – after that it was all too much! He just couldn’t cope!’ White surmised that the likely reason Dupain didn’t stray was because he was ‘frightened of getting lost’. She also noted that his hotel bill for ‘Neuf oeufs’ (nine eggs) revealed that he had not broken with his long-established habit of eating the same breakfast every day, whether in Paris or Castlecrag.

There are other illuminating aspects to Dupain’s ‘Paris experience’. His responses to the alien environment were extraordinarily visceral, as they had been when he had reluctantly visited Bangkok four years earlier on another architectural photography assignment. In a telegram sent to White from Paris, he declared that the tourists flooding the city were ‘here in three dimension[s]! They all smell.’ He found the ‘wild traffic’ daunting and told White: ‘Twice I have saved a person’s life and a bashed-up front end by just yelling in time.’

The personal photographs Dupain took during his days alone in Paris were not exhibited at the time. However, since their incorporation into what is now known as The Paris ‘private’ series in the collection of the Art Gallery of New South Wales, they have been celebrated as an expression of ‘the essence of order, logic and harmony which lies at the core of classicism’. In one sense this is true – the images are rigorously constructed and highly ordered – but in another, they say more about alienation than classicism. They feel different from Dupain’s Australian photographs and are redolent of his position as a stranger, as an outsider. I am left with the impression that the scenes he photographed were receding from him even as he walked towards them with his camera, and that he did not find this experience pleasurable. This feeling of unease is reinforced by the dramatic play of contrasts and preponderance of dark tones.

The way Dupain processed his time in Paris is also revealing. Several months after returning home, he presented Seidler with a gift of twenty-one photographs from their trip (The Paris ‘private’ series) and a letter thanking him. ‘The Paris experience,’ he wrote, ‘was wonderful and did everything to consolidate my thinking.’ This ‘thinking’ did not refer to the potential advantages of international travel but the exact opposite; going to Paris reinforced the beliefs he had formed decades earlier during the war. He would never travel overseas again, claiming that ‘we have it all here’. His view that nothing was to be gained by leaving Australia has a certain irony; Australian artists have commonly spent extended periods overseas and the introduction of cheap international airfares in the 1970s meant that Australians were travelling more than ever before.

Dupain’s dislike of travel wasn’t so much cultural as profoundly psychological and was intimately bound up with the conception of himself as an artist. White observed that he was not someone ‘interested in seeking out the new’. His fear of getting lost physically in Paris mirrored his profound anxiety about losing himself creatively. This related to his long-held identification with Norman Lindsay’s view of artists as exceptional beings who, through ‘sheer brute assertion’, could prevail over less than desirable circumstances. In a piece published in 1980 in Light Vision, Australia’s premier art photography magazine, Dupain gave an unusually detailed outline of his philosophy of life.

Working as a professional photographer in insular Australia has been my self chosen lot. In such a ‘cultural backwater’, as Norman Lindsay expressed it, mental stimulation is anything but over-plus … So one is thrown up against one’s inner resources, and visual excitement comes from over there by proxy in picture books and printed text … Direct influential impact is at half strength capacity. I think this is a good thing if one has the courage and endurance to sustain and promote his individuality by sheer brute assertion of belief in himself.

The implication is clear: Dupain was one of the exceptional men able to meet the challenge.

God help those who can’t muster this will unless they migrate, absorb and return to us, temporarily stimulated and refreshed, but possibly as other human beings lost to their real selves in the wilderness of the world’s pictorial paradise.

To avoid what he saw as the risk of exposure, contamination, and the potential catastrophe of losing his real self, he had no choice but to stay home. He found historical precedents that justified his position, declaring that ‘Rembrandt never left Amsterdam and there’s no evidence to show that Shakespeare ever left Stratford. … So why should I leave Australia?’

So far, I have discussed Dupain’s own perspective on his life and work, but what has been our role in the ‘making’ of Dupain and his photography, both in his lifetime and in the nearly thirty years since his death? This brings me to another aspect of empathy, the notion of complicity. We – writers, curators, and the broader public – are agents who fashion particular narratives about artists and their work. In Dupain’s case, sometimes there was mutual agreement between him and his audience – an intersection of common, vested interests – but sometimes there wasn’t.

What has become clear is that we have created a circular situation in which we keep looking at the same images – a tiny number given the immensity of Dupain’s oeuvre – and are still preoccupied with contextualising his work in terms of modernism and nationalism. Art historian Ann Elias – a rare exception – discusses the neglected area of Dupain’s photographs of flowers, which certainly invite greater attention.

Dupain himself was vague about what constituted Australianness in photography, and his views changed only slightly over time. Immediately after World War II, when he was particularly reflective and keen to act on ‘a fresh outlook, new ideas and possibilities’, Dupain argued for a documentary approach, what he referred to briefly as ‘factual photography’. The task, he declared, was to ‘see and photograph Australia’s way of life as it is, not as one would wish it to be’ and ‘to show Australia to Australians’. To this end, he envisaged a national photography that involved working in the outdoors rather than the studio (which he associated with ‘fakery’), and embraced the qualities of sunlight and ‘naturalness and spontaneity’. Later, he was more inclined to emphasise the importance of a subjective element in photography and what he called an ‘emotional factor’, but he stayed consistent in praising an Australian way of life irrespective of how clichéd such a view had become and how limited his own experience was. He told broadcaster Peter Ross in 1991, for example: ‘We have got a way of life that just does not exist anywhere else that I’ve been [my emphasis]. The tempo of life is much more congenial.’ Ross suggested the core of Dupain’s success was his ‘celebration of the physical life that we lead in this country’.

This brings me to Sunbaker, the most widely reproduced and discussed photograph in the history of Australian photography. Most recently it was the subject of a 2017 exhibition Under the Sun: Reimagining Max Dupain’s Sunbaker. I don’t intend to elaborate on it here, except as an instance where our need for the image usurped Dupain’s.

A little background is necessary: in 1938, on a camping trip with his friends to the South Coast of New South Wales, Dupain exposed some negatives of Harold Salvage, an English friend, sunbaking on the sand. He selected one of these images, which he titled Sunbaker, for inclusion in his monograph Max Dupain (1948). That image subsequently dropped out of circulation and there was no knowledge of its variants until 1975, when preparations were underway for his retrospective at the newly opened Australian Centre for Photography, the flagship for art photography in this country. Dupain presented several hundred prints for the consideration of the curators, ACP director Graham Howe and David Moore. Among them were architectural studies and documentary photographs from earlier decades, which Dupain considered to be his best work, but not Sunbaker. Mindful of his organisation’s brief as the Australian Centre, Howe was ‘looking for something that said “Australia”’ and pressed Dupain on the whereabouts of Sunbaker, his favourite image in the 1948 monograph. Dupain’s response was telling: ‘He said that he wasn’t keen on it, and besides, he had lost the negative.’ He did however acquiesce to Howe’s request to print up other negatives of the same subject, and it was one of these, subsequently known as Sunbaker, that Howe ultimately selected for the exhibition poster and promotional material. Howe attributed its subsequent fame to the media and more specifically to ‘how an audience loves an image that reflects something that is familiar to their own experience. All Aussies have laid on the beach like that and know that particular sensation of sun, water, sand and the sound and smell of the ocean’.

It is often said that artists are poor judges of their own work and their preferences are frequently overridden by their professional collaborators, curators, commercial gallerists, publishers and so on. But it must be emphasised that Dupain was very ambivalent about the elevation of Sunbaker within his own oeuvre and within Australian art photography more generally. He frequently tried to downplay it. He told me in a 1991 interview that its production was a ‘simple matter’ and that he believed it had ‘taken on too much, so much so that you feel one of these days they’ll say that bloody Sunbaker, there it is again’. (That said, between 1975 and 1982 he produced around 200 prints of Sunbaker for sale.)

Crucially, he also tried to direct attention away from Sunbaker and on several occasions nominated Meat queue (1946) as a much better photograph; he had included it in the group he presented to the curators of his 1975 show. Taken in a butcher’s shop in Sydney when meat rationing was still in force, in Dupain’s words, it shows:

four or five females all dressed in black with black hats, not looking too happy about the world, waiting for their turn. Suddenly one of them breaks the queue when I’m focused up all ready to go, see pure luck. She breaks the queue and the dame next to her [gives her] a pretty demoniac look …

Meat queue, 1946, by Max Dupain, gelatin silver photograph, National Gallery of Australia, Canberra. Gift of the Philip Morris Arts Grant 1982 1983.2211

Meat queue, 1946, by Max Dupain, gelatin silver photograph, National Gallery of Australia, Canberra. Gift of the Philip Morris Arts Grant 1982 1983.2211

Meat queue, like Sunbaker, monumentalises the human figure. It has the physicality, authority and graphic power characteristic of his most recognisable works. However, it was a curious choice in a number of respects. It was another old image rather than a contemporary example, and it depicted people rather than architecture or the landscape. Most significantly, it doesn’t champion either an explicitly Australian way of life or a national photography, both of which were so closely associated with Dupain. Indeed, it appears to contradict his own views of a distinctively Australian modus operandi defined by working outdoors in the harsh Australian sunlight. Arguably, Meat queue relates more to a specific knowledge of photographic history, notably the work of French photographer Henri Cartier-Bresson and others who relished the role of chance in their image making. If one of the women had not broken the queue, there would have been no photograph.

The level of success in thoroughly Australianising Dupain was clearly evident by the 1980s. In an article for The British Journal of Photography, 1982, Josef Grosz wrote: ‘to understand Max Dupain, it is, to my mind, essential to know the “feel” of Australia’. He concluded that ‘in some ways Max is Australia’. This conflation reached its apotheosis in the obituaries for Dupain published in the mass media in 1992. In one of the most incisive, in the UK newspaper The Independent, Peter Ride claimed that Dupain’s ‘greatest work’ was ‘of everyday subjects: illustrating a lifestyle and sense of leisure which pin-points exactly the way Australians thought of themselves’. Of the man himself, Ride stated that his characteristics

typified the image of an Australian male of his generation. He could be very blunt and straightforward and exuded both a vigorousness and an easy going manner. These were the sorts of qualities that he seemed to illustrate in the situations he photographed.

In 2000, the year of the Sydney Olympics, Sunbaker achieved a new level of fame after its licensing to Qantas for use in their ‘The Spirit of Australia’ publicity campaign. The irony was that its maker disdained travel.

One of my favourite books is David Malouf’s The Conversations at Curlow Creek, because of the way the two principal characters become unopposed at a crucial juncture. The physical space they occupy falls away and another opens up in which ‘the normal rules of separation, of one thing being distinct to itself and closed against another, no longer applied’. Malouf’s metaphor of an ‘open’ space is useful in illuminating what is simultaneously an abstract and concrete process – trying to imagine different ways of thinking and writing about Dupain’s photography that recognise his vulnerabilities, fears, contradictions, and failings, as well as our own. There is of course a larger point to such an endeavour, and it’s also open-ended: how can our reimagining of Dupain’s photography amplify our understandings of Australian society, art, and culture in his lifetime and since?

I am not an apologist for Dupain. His attitudes to race, eugenics, masculinity, and feminism have been rigorously critiqued by writers such as Geoffrey Batchen and Isobel Crombie, and there is still much more to be done. Nor am I seeking a biographical reading of his photographs, a practice that is inherently reductive and simplistic. But, at the same time as registering his predilection for the monumental and monolithic, for imposing himself on his subjects and making photographs that are assertions rather than invitations or ruminations, I am starting to notice other things. Strangely enough, this takes me back to Meat queue and the quiver of energy, which Dupain described as chance, caused by the simple action of a woman breaking the queue. That uncontrolled, uncontrollable quiver keeps reappearing in Dupain’s photography, up to the last. In one of his many late flower studies, Cattleya orchid, 1991, a petal flutters just enough to escape sharp definition.

When Peter Ross interviewed Dupain in 1991, he speculated that he was looking for ‘a sort of solidity’ in his photography, ‘trying to find some sort of order out of where we live’. And a few months after Dupain’s death when broadcaster Phillip Adams asked Gael Newton what he was like, she gave the memorable answer, ‘Rock on the outside, water on the inside’.

References

Peter Adams, ‘Max Dupain: Depth of field. Depth of feeling’, Industrial & Commercial Photography, March-April 1984.

Candida Baker, ‘Capturing landscapes of the heart, the Age, 26 November 1988.

Jill Crossley, correspondence with the author, January 2020.

Max Dupain, ‘Factual photography’, Oswald L. Ziegler, ed., Sydney, Ziegler Gotham Publications, Australian Photography 1947, 1948.

Max Dupain, Max Dupain’s Australian Landscapes, Ringwood, Vic., Viking, 1988.

Max Dupain, ‘Max Dupain’, Light Vision 5, 1978.

Max Dupain, ‘Past Imperfect’, Max Dupain’s Australia, Ringwood, Vic., Viking, 1986.

Ann Elias, Useless beauty: flowers and Australian art, Newcastle upon Tyne, Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2015.

Helen Ennis, interview with Max Dupain, ‘Max Dupain: Photographs’, Canberra, National Gallery of Australia, Canberra, 1991.

Josef Grosz, ‘Max Dupain: an appreciation’, British Journal of Photography, 15 January 1982.

Graham Howe, correspondence with the author, 2019.

David Malouf, The conversations at Curlow Creek, London, Vintage, 1997

Robert McFarlane, quoted by Geraldine O’Brien, ‘Exit, an old master’, Sydney Morning Herald, 30 July 1992.

Gael Newton, Interview with Philip Adams, ABC Radio, transcript, http://www.adrianboddy.com/?p=793 Accessed 11 January 2021.

Helen O’Neill, A Singular Vision, Harry Seidler, Sydney, HarperCollins, 2013.

Helen O’Neill, ‘Max Dupain’s lost shots of Paris’, https://www.afr.com/life-and-luxury/arts-and-culture/max-dupain-s-lost-shots-of-paris-20131102-iyyw4

Peter Ross, ‘Sunday Afternoon with Max Dupain’, ABC Radio 1992, transcript, http://www.adrianboddy.com/?p=793 Accessed 11 January 2021.

Photographers of Australia, documentary film, 1992

‘The Paris ‘private’ series’ https://www.artgallery.nsw.gov.au/collection/works/398.2012.16/

Comments powered by CComment