- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Old man yells at cloud

- Article Subtitle: Christos Tsiolkas turns to autofiction

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

On page 20 of my advance copy of 7½, I insert a line in the margin: ‘Starting to sound like Sōseki’s Kusamakura here’. I had met the author of the passage – a man named Christos Tsiolkas – at the Sydney Writers’ Festival in May, sidling up to the Clare Hotel breakfast bar at an enviably early hour each morning to enjoy fruit and festival conversation. As my pen hovers, I wonder how that gregarious and personable figure squares with the bittersweet register of this novel.

- Article Hero Image (920px wide):

- Article Hero Image Caption: Christos Tsiolkas (photograph by Zoe Ali/Allen & Unwin)

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Declan Fry reviews '7½' by Christos Tsiolkas

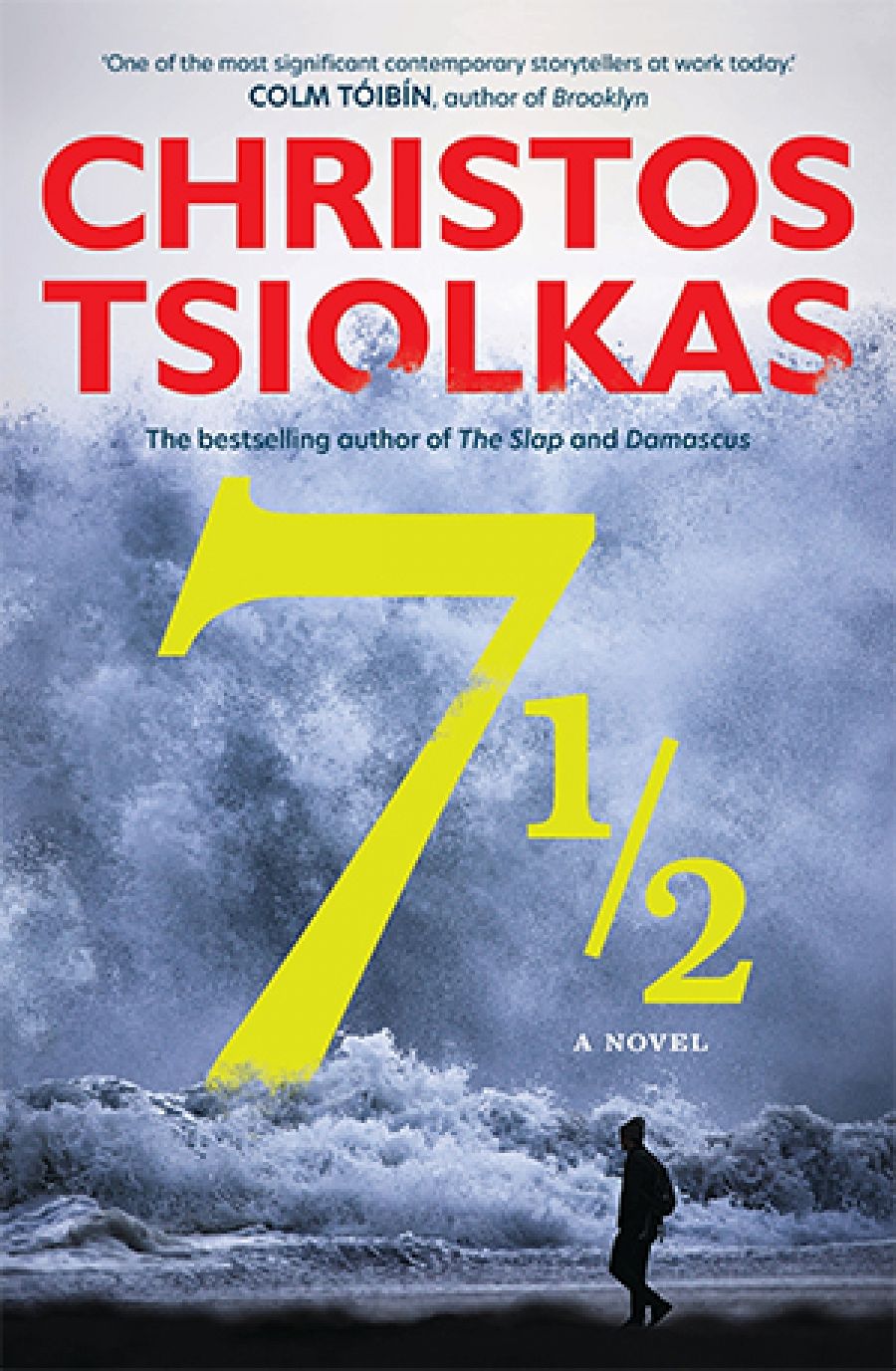

- Book 1 Title: 7½

- Book 1 Biblio: Allen & Unwin, $32.99 pb, 342 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/Jr44ME

Our narrator is an authorial surrogate. His name is Christos Tsiolkas. He is struggling to write a novel. Titled Sweet Thing, it concerns Paul, a character inspired by real-life porn actor Paul Carrigan. Tsiolkas’s surrogate indulges in frequent walks and swims, hoping to encounter beauty and counter ‘the inevitable sag of my ageing body’. His progressive friends worry that he has gone soft in other ways: his ardour for changing the world seems to be in abeyance. ‘[P]olitics, sexuality, race, history, gender, morality, the future – all of them now bore me,’ he admits. Aggrieved by sanctimonious online posturing, he alternates between old-man-yells-at-cloud dyspepsia and reinventing Eileen Myles’s ‘Everyday Barf’: ‘The simple nature of our craft is how to vomit these stories out on a page. [...] By defining the novelist’s art as a hurling, a spewing, I am being deliberately crude, because I am writing at a time when the novel is unbearably timid.’

Certainly, few of us might enjoy or claim unalloyed pleasure in the accoutrements of our age. We were promised flying cars; instead they gave us hellsites. 7½ is largely a meditation on disappointment: failing ideological faith, failing body, failing novel.

Tsiolkas also considers the greatest artistic failure of all: the dysfunctional relationship between life and fiction. From Balzac’s painter Frenhofer in ‘The Unknown Masterpiece’ to Henry James’s author Dencombe in ‘The Middle Years’, the work of art and art-making has often figured as a record of defeat. 7½’s narrator hopes to ‘separate my fiction from my truth’, yet finds the word ‘truth’ ‘inadequate’: ‘I am writing about my past [...] It clearly is as much memoir as it is fiction. The writing of one demands the same craft one uses for the other.’

Despite what Tsiolkas’s narrator may maintain about ‘craft’, the techniques of fiction are not necessarily identical to those of memoir: the felicity demanded by memoir is largely distinct from fiction’s imaginative licence. This difference explains, in part, why the two genres are distinct, quite apart from considerations of the reader’s need to distinguish social realism – with its desire to represent the world ‘out there’ – from questions of veracity peculiar to memoir and other temps perdu remembrance.

Woolf, Joyce, Genet (source of 7½’s epigraph), Duras, Bellow, Baldwin, Roth, Lorde (who described her ‘biomythography’ as ‘fiction built from many sources’), Coetzee, Murnane, Carey: all wrote from their lives; none purported to be creating anything other than fiction. Keep in mind that autofiction is a species of fiction – at least, as I believe it should be, when read with awareness of its conditioning fictional properties. This is how these authors’ novels succeeded: they played with the idea of borrowing from one’s life, from friends’ and family’s lives, without demanding this interpretation, or indeed any appraisal that would haphazardly draw the life in.

Repurposing creative narrative to serve fiction and memoir only gives it the freedom to fail as both. Tsiolkas knows this: his second novel, The Jesus Man (1999), weaved the voices of its characters alongside an ‘I’ voice that felt authorial without ever needing to imbue this narration with autofictional characteristics – sharing a name and profession with the author, for example, or metafictional gestures toward the creation of the book itself. Jump Cuts (1996), his brilliant and subtly experimental memoir-of-sorts (with Sasha Soldatow) similarly gave voice to both writers without claiming to be anything other than ‘non-fiction’, achieving a kind of sustained collaborative criticism in the process. When the narrator of 7½ describes hoping for ‘safekeeping between the story I tell of Paul and the story I tell of myself’, it is hard not to feel he would have been better served telling each story in separate books. Splicing the two together diminishes both and flatters neither.

If we call 7½ a novel, it’s an unsuccessful one: the novelising is weak and continually interrupted by memoir. Call it memoir, on the other hand, and we would have to concede that its autobiography is hampered by the half-sketched novel that keeps popping up. The only practical reason ‘autofiction’ seems to be employed here is to grant Tsiolkas an authorial surrogate who can narrate his experience of struggling to write Paul’s story in its own right. This isn’t necessarily fatal, but the story itself, a shaggy dog number, is.

So I found myself wondering: what if failure is the point of 7½? Tsiolkas leaning into failure as an artistic goal? This raises the question of critical generosity: can the critic be accommodating enough to inhabit failure – to stay with the trouble; perhaps even choose, like the author, to lean into it?

These considerations are prompted largely by the narrator’s process: he describes creating characters as akin to meeting them ‘in a mirror’. Those who refuse to emerge, he writes, are ‘trapped behind [it]’.

We have been conditioned to believe that art functions as a reflection of the world, a mirror carried along a road. The line, as Northrop Frye remarked, between fiction and non-fiction is one of belief, the reader’s willingness to lend credulity to the story being told. Tsiolkas plays on our desire to know the author despite being cognisant of authorial intervention and the mediation of narrative: inviting the reader behind the scenes, gently patting the seat nearby, ushering us in.

I doubt that it would disgruntle acolytes of New Criticism to note that, in describing Tsiolkas as an enthusiastic user of the Clare Hotel’s breakfast bar, I was not joking so much as making a character observation. He is an enthusiast – an avid appreciator. Tsiolkas is an antipodean D.H. Lawrence; he evinces Lawrence’s sensuous appraisal, the desire to see beneath the skin of things. Both are working-class writers intent on urging language to say something true – something unmediated, so to speak. Yet Tsiolkas’s narrator doubts the capacity of language to convey beauty in our ‘ungallant age’. Worshipping at Dionysus’s altar, he is frequently exercised by contemporary Puritanism.

The bogey of the censorious audience – some vague authority figure slamming 7½ down, shouting, ‘You’re a loose canon, Christos! They’ll cancel you if this ever gets out!’ – does not justify the novel’s coy ‘oh-now-this-will-get-me-in-trouble’ poses. Tsiolkas’s surrogate declares that ‘[t]here is an ugly rancour that refutes the link between biology and sex [...] Those who rail against the biology of gender and sex are as suspicious and hateful toward the body as were the most pious of early Christian moralists’. Whatever one thinks of this – a gracious reader might grant that Tsiolkas is adverting primarily to the body, urging us not to confuse nature’s indifference with anthropocentric vanities – the phallocentrism of his writing should give readers pause. ‘[Nature] is no simpering mother,’ the narrator reflects, observing a tree trunk. ‘Manet understood her: that protruding trunk is Mother Nature’s scandalous swinging cock; this mother has power.’

Forget the Jesus guy: Lawrence wept.

Comments powered by CComment