- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: ‘The momentum of the general’

- Article Subtitle: Edward Said’s worldliness

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

When the leukaemia with which he had been diagnosed in 1991 claimed his life twelve years later, Edward W. Said left behind more than the usual testaments to a successful academic career: landmark studies, bountiful citations, bereft colleagues, and the cadres of pupils whose intellectual maturation he had overseen. More importantly, he embodied a many-sided ideal of intellectual and civic engagement that combined the vita contemplativa with the vita activa. A professor in Columbia University’s Department of English and Comparative Literature for forty years, Said was a member of the exiled Palestinian National Council and arguably the most visible advocate for the Palestinian cause throughout his later life.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

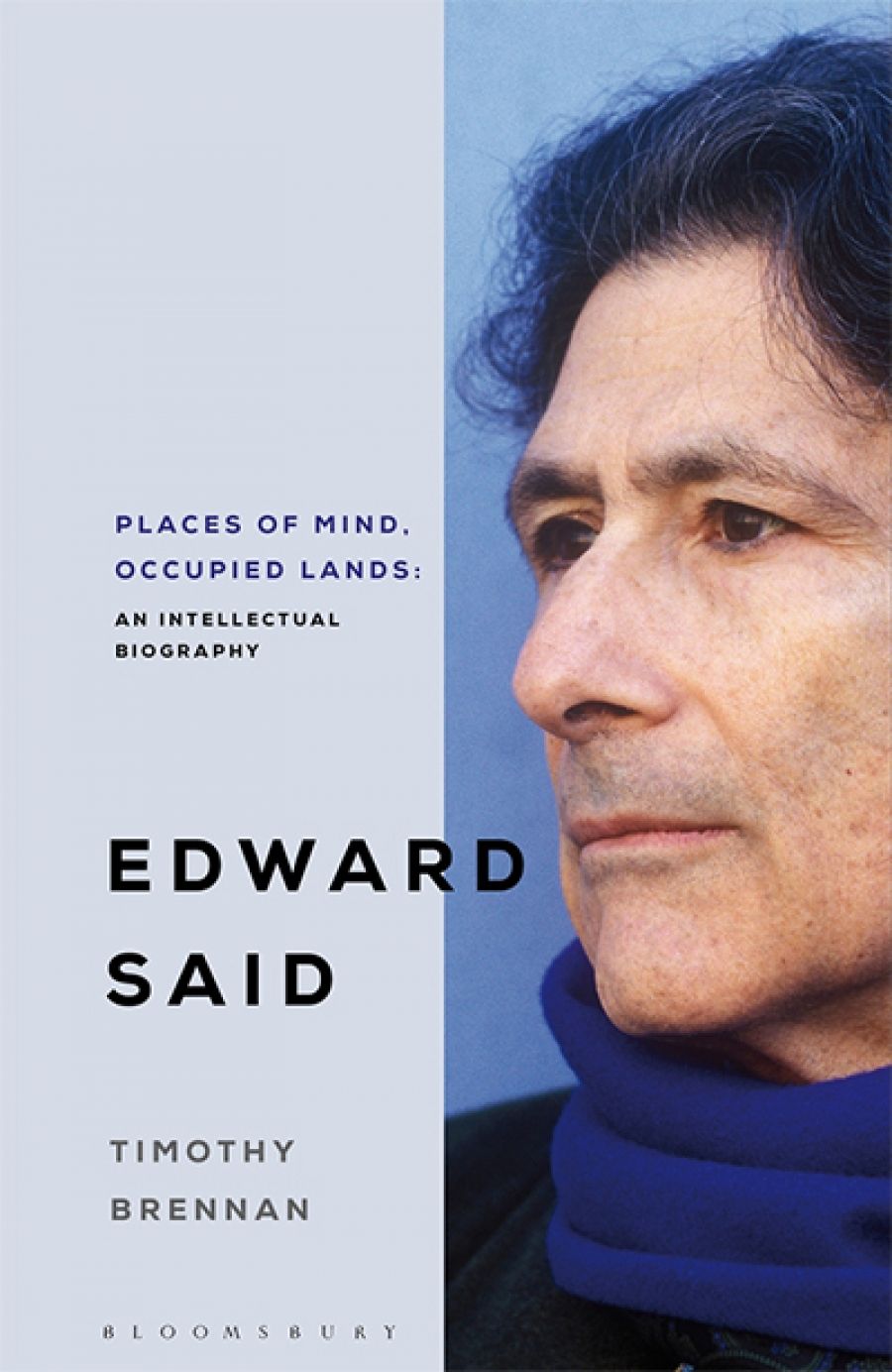

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): James Jiang reviews 'Places of Mind: A life of Edward Said' by Timothy Brennan

- Book 1 Title: Places of Mind

- Book 1 Subtitle: A life of Edward Said

- Book 1 Biblio: Bloomsbury, $49.99 hb, 456 pp

Among the many terms that Said either coined or made his own – ‘orientalism’, ‘contrapuntal’, ‘exilic’, ‘filiation’ and ‘affiliation’ – perhaps none is more important than his concept of ‘worldliness’. Said was undoubtedly ‘worldly’ in the ordinary sense of the word: well travelled, cosmopolitan in sensibility, a shrewd observer of power and prestige. But he gave it a more emphatic and more general cast. As he put it in The World, the Text, and the Critic (1983): ‘texts have ways of existing that even in their most rarefied form are always enmeshed in circumstance, time, place, and society – in short, they are in the world, and hence worldly’. This was especially worth keeping in mind with respect to critical texts produced by literary scholars – so keenly perceptive about the vintage and provenance of their sources, yet by and large oblivious to the variegations of their own terroir.

One of the upshots of this ‘worldly’ insight is that much of Said’s best work – I am thinking here particularly of his essays on the state of criticism – directly addresses its context, taking the ground and climate of opinion, scholarly or political, for its explicit subject. If a large portion of the biographer’s job is to weave his or her subject back into the thick web of contemporaneous circumstance, then any biographer of Said will necessarily find themselves a little squeezed by Said’s pre-emption.

Timothy Brennan’s Places of Mind: A life of Edward Said meets this unique challenge impressively through scrupulous archival research and some deft draughtsmanship of the shifting intellectual and political topography ranged over by his doctoral thesis adviser. Brennan’s biography is revealing about the complex genealogies of Said’s books, from the enframing ambitions that never came to fruition (such as the book-length study of intellectuals and the monograph on Jonathan Swift) to the stimulation provided by writing for an Arabic-speaking audience (the case for translating Said’s 1972 essay ‘Withholding, Avoidance, and Recognition’ could not be clearer).

What emerges most distinctly from Brennan’s portrait are not the lineaments of a gifted ‘mind’, but rather the sheer messiness of thinking for a living, as Said’s critical instincts are tested against the practical exigencies of statecraft. The messiness partially explains Said’s affinity with Swift: for both writers, a constitutive restlessness was ignited into fierce eloquence (Swift’s epitaphic saeva indignatio) by the cruelty and ignominy of colonial domination. Said’s most ambitious arguments, such as that forwarded in Orientalism (1978), have tended to invite misapprehension (including, as Brennan has shown in Wars of Position [2006], that book’s purported relationship to postcolonial studies). Though not always airtight, they appeal by pointing the way to somewhere less plagued by partiality, all the while ‘acquiring and expressing’, as Said once put it, ‘the momentum of the general’.

True to Said’s own critical ethos, Places of Mind is not sacralising hagiography but a thoroughly secularising chronicle. It oscillates between a defensive posture over an embattled intellectual legacy and a scepticism towards Said’s own habits of self-mythologisation. In the preface, Brennan writes that ‘we might even see today’s “post-critical” age (including in academia) as the establishment’s revenge on him’, an acknowledgment of the trend in literary studies away from the hermeneutics of suspicion (the arraigning of texts on charges of ideological complicity) towards a hermeneutics of attachment, of openness and pleasure (a word Said seldom fails to include in his characterisations of literary study). Said’s snubbing by the fellows of King’s College, Cambridge, who ‘turned him down for an honorary degree when others half his stature were given the honour without a second thought’ (a determination overturned under the urging of a dissenting group headed by Ian Donaldson) causes vicarious smarting. The indiscriminate diss (‘others half his stature’) is an odd lapse for Brennan, who otherwise evinces admirable coolness towards the politics of institutional prestige.

But Brennan isn’t afraid to burst his subject’s self-hallowing bubble, especially in his account of Said’s early life in Cairo and his time at Mount Hermon, an élite Massachusetts preparatory school where Said was sent in 1952 after his poor disciplinary record in the British colonial education system threatened to narrow his prospects. Here, Brennan’s account supplements Said’s memoir, Out of Place (1999), which showed its author suffering under the strict disciplinary regimens of paternal expectation and formal schooling, as well as from inconstant maternal affection. Brennan reports that Said’s sisters ‘were appalled by his portrait of his parents’ and surmises that ‘the burdens of a childhood without relaxation or leisure seem more the outcome of a relentless inner drive than the work of meddling parents for whom every achievement was a flaw’.

Similarly, by drawing on Said’s Mount Hermon records and correspondence, Brennan complicates Said’s sense of never feeling ‘fully a part of the school’s corporate life’, presenting his subject as ‘a rather eager participant’ and ‘positively jaunty in his letters to his superiors after graduation’. Despite his admiration for Theodor Adorno’s brand of kulturkritik, Said was very much at home in America and American culture, and it is one of Brennan’s most striking observations that ‘for all his writing on exile, [Said] was a rooted man – imaginatively in Palestine and actually in New York’. Indeed, shortly after taking up a position at Columbia, Said was introduced to the New York literati by his colleague F.W. Dupee, a founding editor of Partisan Review, and for most of his professional life Said produced a steady stream of reviews and essays for the city’s popular press (where he was decidedly less welcome after the publication of The Question of Palestine [1979]).

The concept of ‘place’ recurs as a ground note throughout Brennan’s biography (as it does throughout Said’s oeuvre), which reproduces an unpublished letter to The New York Times by Said’s friend Andre Sharon in response to the aspersions cast upon Said’s Palestinian identity: ‘There were no meaningful frontiers when we were growing up, particularly mental ones [...] It mattered much less to the inhabitants that they were from Iraq or … Saudi Arabia or Oman than it did to the Foreign Office or the Quai D’Orsay.’ It’s difficult not to notice a parallel between Sharon’s ‘meaningless’ geopolitical frontiers and the adventitious disciplinary boundaries abjured by Said: both kinds of barrier were bureaucratic fictions designed to inculcate governability rather than capture anything of the shape and texture of actual life.

Said was a steadfast defender of intellectual generalism, even going so far in his 1993 Reith Lectures as to advocate for amateurism. For like the exile, the amateur had the advantage of a double perspective, being ‘both in and out of the game’, in the words of Walt Whitman. Part of this was temperamental – Said was drawn to autodidacts such as R.P. Blackmur and Giambattista Vico – but it was also polemical. Said’s growing disenchantment with post-structuralist and even some Marxist strands of critical theory had to do with the burgeoning divide between intramural institutional politics and ‘the politics of struggle and power in the everyday world’. In one of his most devastating essays, ‘Opponents, Audiences, Constituencies, and Community’ (1982), Said argued that the ethos of ‘non-interference and rigid specialization in the academy’ was an extension of laissez-faire neoliberalism in the Age of Reagan. Even oppositional literary critics such as Fredric Jameson, for all their interpretative prowess and political commitments, only thickened literary criticism’s air of ‘cloistral seclusion’ insofar as these writers’ ‘assumed constituency’ remained ‘an audience of cultural-literary critics’.

Elsewhere, Brennan has written with acuity about Said’s generalism, and the difficulty of pinning down a generalist’s intellectual coordinates is amply demonstrated in the chapter ‘A Few Simple Ideas’, where Brennan examines Said’s relationships to Marxism, psychoanalysis, and feminism. The first of these is given the most sustained treatment, but also gives rise to the greatest discordance. There’s something slightly dogmatic and high-handed about Brennan’s procedure in identifying the ‘liberal-centrist’ tendencies in Said’s thought and in averring that Said was ‘rightly censured’ for having ‘corralled Marx into the camp of John Stuart Mill’ in Orientalism. Whether or not Said was ‘a Marxist’, his debt to the Marxist intellectual tradition was never in question. Brennan, of course, knows this, but it is symptomatic of what Said described as the ‘self-policing, self-purifying’ tendency within academic circles that an essay like his ‘Secular Criticism’ can be dismissed by Brennan as a piece of liberal cant when its very argument is poised against the coercive (and patronising) orthodoxies underlying institutionalised affiliation.

In ‘Secular Criticism’, Said offered a salutary reminder to those ‘who maintain that criticism is art’: ‘the moment anything acquires the status of a cultural idol or a commodity, it ceases to be interesting’. Said’s prominence both within and without the academy has put him at risk of becoming an approved cultural object. He lived long enough to see some of his own arguments and concepts harden into modish clichés, a process that the consciously unfashionable calls to philology and humanism late in his career could not reverse. But all Said’s interventions, from his turn against post-structuralism to his critique of Zionism, follow a consistent pattern: they refuse to allow any cause, no matter how noble its inaugurating motives, to devolve into a special interest. It is this that he meant by worldliness.

Comments powered by CComment