- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Short Stories

- Review Article: Yes

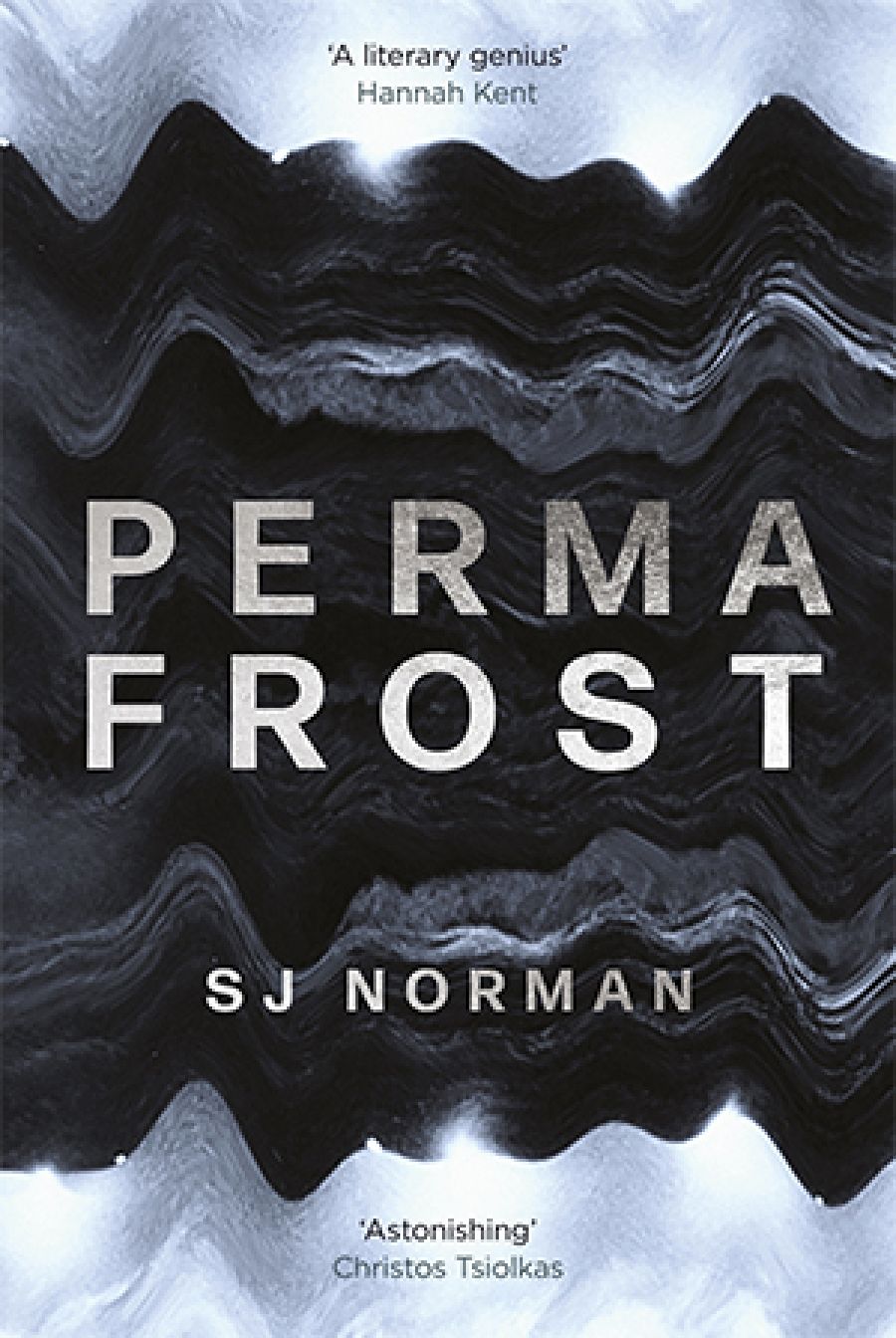

- Article Title: ‘Hot, red proof of life’

- Article Subtitle: S.J. Norman’s impressive short story collection

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Ambiguity, done well, has a bifurcating momentum that can floor you. The late Argentinian writer Julio Cortázar, a master of unsettling short stories shot through with ambiguity, knew this and used it to pugilistic advantage, declaring that ‘the novel wins by points, the short story by knockout’. Ambiguity is likewise central to S.J. Norman’s début collection, Permafrost, seven eerily affecting stories that traverse and update gothic and romantic literary traditions, incorporating horror, queer, and folk elements to hair-raising effect. No matter how often you read these spectral tales, they simply refuse to resolve themselves definitively. It could be that things have gone spectacularly wrong and that, simultaneously, everything is okay – a see-saw in constant motion, made all the creepier by the fact nobody is sitting on either side.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Paul Dalgarno reviews 'Permafrost' by S.J. Norman

- Book 1 Title: Permafrost

- Book 1 Biblio: University of Queensland Press, $29.99 pb, 213 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/MXb9DY

The stories (or rounds, to extend the boxing metaphor) feature first-person narrators about whose backgrounds we might learn something, or practically nothing. We do glean where they are in the world (Japan, the United Kingdom, Germany, Australia), but their identity – even their gender – is obscured. We might guess that a male customer’s apology to the narrator in ‘Secondhand’ – ‘Sorry, love. Sorry’ – outs the narrator as female-identifying, but Norman is adept at toying with our assumptions, sprinkling each story with ludic grains that contribute to the book’s purposefully shifting sands.

Each of the narrators is somehow isolated, whether sitting in an empty schoolyard, marooned in a block of apartments, or momentarily left behind in a gruesome tourist attraction, settings that provoke a peculiar shade of Kubrickian unease: there should be other people in these locations, maybe even lots of people, so where are they?

The difficulty the narrators have connecting with others is sometimes literal (a bad phone line) and sometimes lateral (they’ve transported themselves physically or emotionally). But, in all cases, they’re on the periphery, haunted by the ‘pressurised memory’ of the past, or a ‘sense of having disturbed something’ in the present. Various entities lurk and lurch just out of frame: a volcano hidden behind the trees in Japan, a county in which the ‘dead are with you always’; books roiling with ‘the touch of invisible hands, the clamour of inaudible voices’; a piano motif emanating unexpectedly from a recording in an all-but-empty house. As one narrator tells us: ‘Humans, like other living creatures, are more palpably affected by all the things we can’t hear, than the things we can.’

Displacement is a big theme, communicated most obviously via the locations – supposedly cheap and cheerful country retreats that confound expectations, overseas trips that clearly haven’t gone to plan. There are always pros and cons, of course. As one character in the title story puts it: ‘sometimes not belonging is a wonderful thing. Sometimes it’s just what you need.’ But displacement also abounds in the psychological sense, with objects and visual stimuli doing heavy symbolic lifting in the form of transference and transmogrification.

In ‘Whitehart’, the narrator creeps into a seemingly abandoned orchard in a woodland clearing, steals some apples, and cycles off, unperturbed that their ankles have been injured by thorns – ‘I realised I was bleeding quite badly. It felt fantastic.’ But this ‘[h]ot, red proof of life’ and the childlike transgression of stealing apples (which, as any Brothers Grimm fan will know, cannot go unpunished) commingle and re-emerge alongside other morphing details, propelling the narrative in unnerving ways.

Psychogeography – in the sense of places holding the psychic charge of what’s transpired in and on them – comes to the fore most explicitly in the description of Oświęcim, the Polish town flanking the Auschwitz–Birkenau concentration camps, which is ‘occupied by the living, who co-exist with the multitudinous dead’, but it’s prominent in several of the other stories, too, with an accretion of past lives and place-specific emotions that return and impose themselves.

Atmospherically, the collection swings between the oneiric and nightmarish, a deliberately uncertain melange of sleepwalking, night terrors, and potential psychosis. One of the only criticisms is that, taken together, the stories lean a little heavily on this particular ambiguity (are the characters dreaming or awake?) as our narrators fall into and emerge from ‘sleep stretched so thin with dreams it barely felt like sleep’.

Many of the questions at the heart of the book relate to loss and what we do with it. Does it stay with us? Does it disappear? And if its shadow slinks from us, where exactly does it go? Such concerns are raised iteratively and implicitly throughout, culminating in the last – and by far the longest – story in the collection, ‘Playback’. This structure gives the impression of a talent flourishing, with Norman’s preoccupying themes given more space to breathe (even if, due to the tale’s spookiness, they are shallow breaths for the reader).

In tone and execution, ‘Playback’ is also the closest to Cortázar’s ‘House Taken Over’, a 1946 tale in which a brother and sister attempt to live their lives unencumbered while their ancestral home is progressively ‘taken over’ by unknown entities. But the narrator in ‘Playback’ lacks even the comfort of a sibling to share in the unfolding mystery. Instead, they are accompanied by the memories of a partner who has recently abandoned them, and their late mother’s words that it is ‘possible for a living person to become a ghost’.

‘Playback’ offers the last chance in Permafrost for a clean knockout. But in this story and others, S.J. Norman demonstrates that there is often more horror to be wrought from the blows that leave us conscious.

Comments powered by CComment