- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Memoir

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: The good lie

- Article Subtitle: An unsung Australian prophet

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

When did the rationale for the Iraq War – which began in 2003 and still rumbles today – go from being a mistake, to a self-deception, to an outright lie? When did it dawn on the Bush Jr administration and its key allies in London and Canberra that the ostensible reason for the invasion of Iraq had disappeared, probably literally, under the sands of Mesopotamia? By the time of the invasion, Saddam Hussein’s regime possessed no weapons of mass destruction that could threaten another country. The Iraqi dictator may have desired such weapons, but a combination of international sanctions and the mere fear of retribution thwarted his plans.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

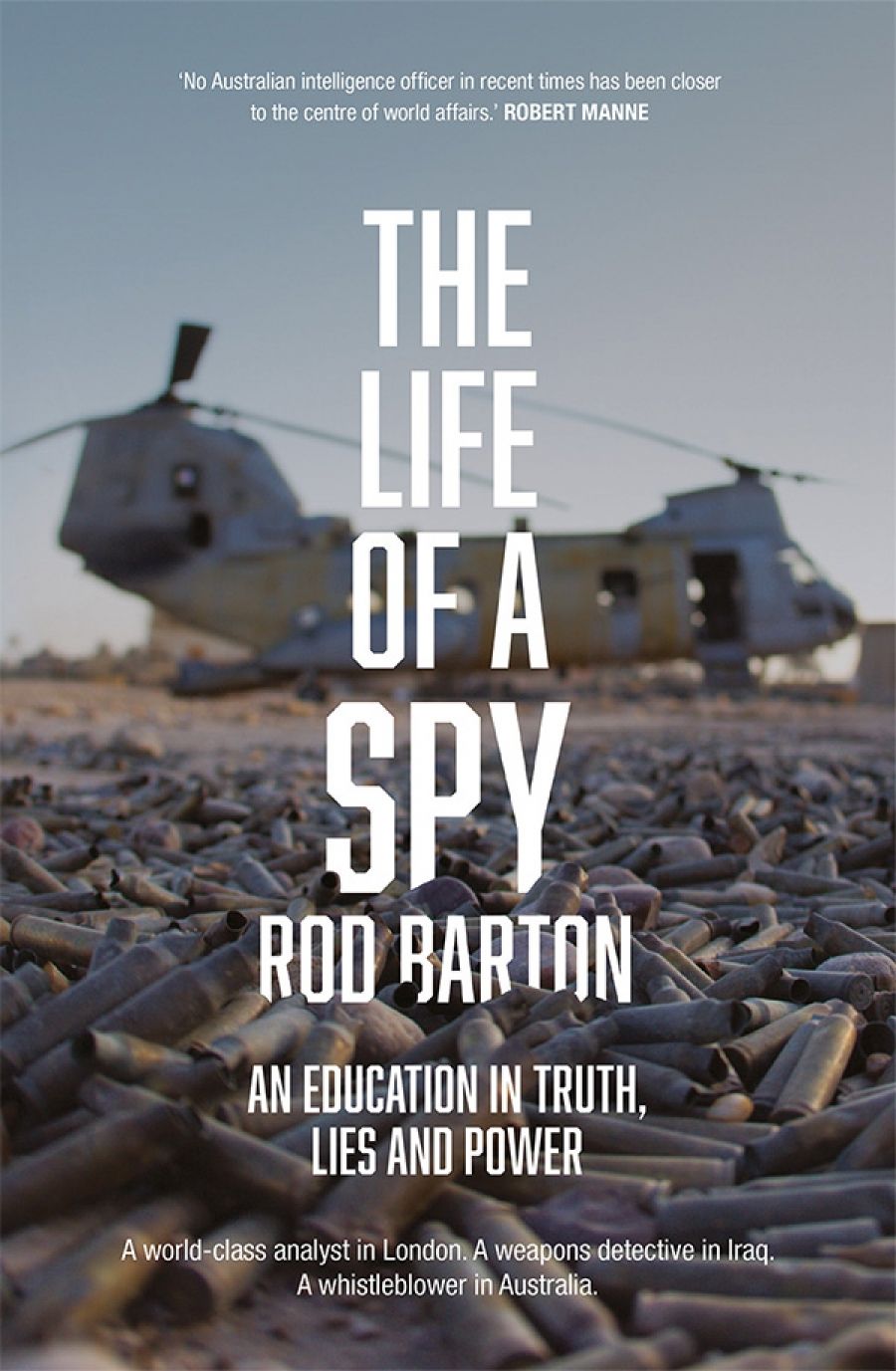

- Book 1 Title: The Life of a Spy

- Book 1 Subtitle: An education in truth, lies and power

- Book 1 Biblio: Black Inc., $32.99 pb, 304 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/AogBV7

At the centre of the effort to uncover the truth was an Australian scientist and intelligence officer, Rod Barton. His new book, The Life of a Spy, methodically builds the case that what began as genuine fear in the West about Saddam’s plans for a nuclear, biological, and chemical arsenal ended as an exercise in old fashioned arse-covering.

Barton spent close to ten years in and out of Iraq, working mainly for the United Nations as a weapons inspector. He was an officer with the Defence Intelligence Organisation and an adviser to the CIA. But – and this is telling – he was never fully trusted by the ideologues at Langley, where the CIA is headquartered. Barton simply did not share their penchant for the ‘good lie’, the untruth that justified the supposedly grander plan.

When Barton could not find any weapons of mass destruction, he wanted to do something radical – say it. It would end with his own government freezing him out because he had embarrassed its friends in a foreign spy service.

The first time Rod Barton understood the mendacity of the Central Intelligence Agency was in Indochina, and it centred on something as mundane as shit. It was 1981 and, with degrees in microbiology and biochemistry, he was a junior analyst with Australia’s Joint Intelligence Organisation. On the Thai-Cambodian border, he was interviewing refugees who had fled when Vietnam invaded Cambodia in 1979 to drive out the genocidal Khmer Rouge.

It is worth noting that the Washington Post reported in September 1980 that the United States would continue to support the Khmer Rouge as the representative of so-called ‘Democratic Kampuchea’, despite its murder of an estimated two million people. Among the refugees were ‘resistance fighters’ who claimed the Soviets were supplying the Vietnamese with a yellow, powdered chemical weapon. The CIA had collected samples of this powder and had detected, it claimed, mycotoxins. The CIA and State Department declared it ‘yellow rain’, a sly parallel to the Agent Orange that the United States had used to destroy swaths of Vietnam. But mycotoxins would cause blindness, and not a single case had been reported. A Harvard professor soon uncovered the truth. ‘Through private investigation,’ writes Barton, ‘he had discovered what all beekeepers know well: bees often defecate in swarms and their faeces often falls to the ground in sticky droplets like rain.’ The CIA had collected dried bee poo. The CIA, invested in the narrative of Vietnam spraying its own version of Agent Orange, tried to discredit the professor and Barton. It never corrected its mistaken intelligence. ‘The CIA is not an organisation to be easily crossed,’ Barton observes.

Fourteen years later, Barton is back on the weapons beat, having earned respect for his work on Somalia’s recovery from civil war. The United Nations Special Commission (UNSCOM) on disarmament seconded him from Australia’s Defence Intelligence Organisation to work in Iraq. Saddam had been driven from Kuwait in 1991, but the US-led forces left him in place. Iraq was under severe sanctions, and legitimate fears remained about its weapons aspirations.

Barton joined UNSCOM with an open mind. He is typical of many who questioned America’s rationale for going to war with Iraq again, this time in 2003. They were credible, experienced people, often diplomats and scientists deeply experienced in dealing with weapons. They were anything but the anti-war rent-a-crowd that George W. Bush, Tony Blair, and John Howard decried. They held no brief for the Iraqi regime, and, as Barton reveals, they were exhaustive in their hunt for weapons of mass destruction. But they knew when – and why – to stop hunting. In the mid-1990s, Barton did discover some haphazard attempts to cultivate a chemical and biological program under the guidance of a smart, British-educated scientist, Rihab Taha. Known as ‘Dr Germ’, she oversaw the build-up of alarming quantities of bacterial growth that could be used in anthrax. ‘Dr Germ’ and her menacing husband, General Rashid, were evasive and obstructed the weapons inspectors.

In 1995, the Iraqis, desperate to end sanctions and knowing the threat of armed action, admitted that they had tried to build an anthrax program. The inspectors ultimately found that even if Iraq did develop chemical and biological agents, it had no capacity to weaponise them or to deliver them beyond its borders. In 2000, Barton told an Australian parliamentary inquiry that Iraq was effectively disarmed.

Then came 9/11. Iraq had nothing to do with the Al Qaeda attacks on the United States, but Barton believes they created the momentum for the Bush administration to invade Iraq eighteen months later. Bush made a series of false claims about UN findings on Iraq, and Tony Blair, the UK prime minister, produced his dubious ‘Dossier’ about Saddam’s supposed weapons capabilities.

In the aftermath of the invasion, Barton would return to Iraq for a final tour of duty and confirm what he already knew. The Iraq Survey Group, set up by the Americans to find the weapons and to which he was attached, was effectively a CIA operation and here the situation turned from the deceptive to the farcical. Two of the analysts working on the operation (Barton calls them ‘Laura’ and ‘Sharlene’) were constantly missing deadlines for their reports on how the search was proceeding. They were fudging their findings. ‘Soon I discovered that they had each made major contributions to the pre-war intelligence assessments in Iraq,’ he recalls. ‘My guess was that they now did not want to write anything that might contradict these assessments. Careers are made and lost on such matters.’

We know how this story ends. We know that, briefly and desperately, the Bush administration and its apologists tried to refashion the Iraq invasion as a humanitarian intervention to end Saddam’s dictatorship. And we know they bequeathed a chaos that led to the self-styled Islamic State, a force that would surpass Saddam, the Taliban, and even Al Qaeda in its brutality and depravity.

Rod Barton was a prophet, unsung. This book is his testament.

Comments powered by CComment