- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Literary Studies

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Freedom and possibility

- Article Subtitle: Portrait of a year in poetry

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Sarah Holland-Batt’s Fishing for Lightning is a book about Australian poetry. As such, it is a rare, and welcome, bird in the literary ecology of our country. It is welcome because poetry, like any other art form, requires a supportive culture that educates and promulgates. Not that Holland-Batt, herself one of our leading poets, is ‘merely’ didactic, or a shill for the muses. Holland-Batt, who is also an academic, writes with great authority and insight, and she is a fine stylist, penning essays that are packed with humour and playfulness. These essays cater for all kinds of audiences, from newcomers to poetry experts, which is no small feat.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): David McCooey reviews 'Fishing for Lightning: The spark of poetry' by Sarah Holland-Batt

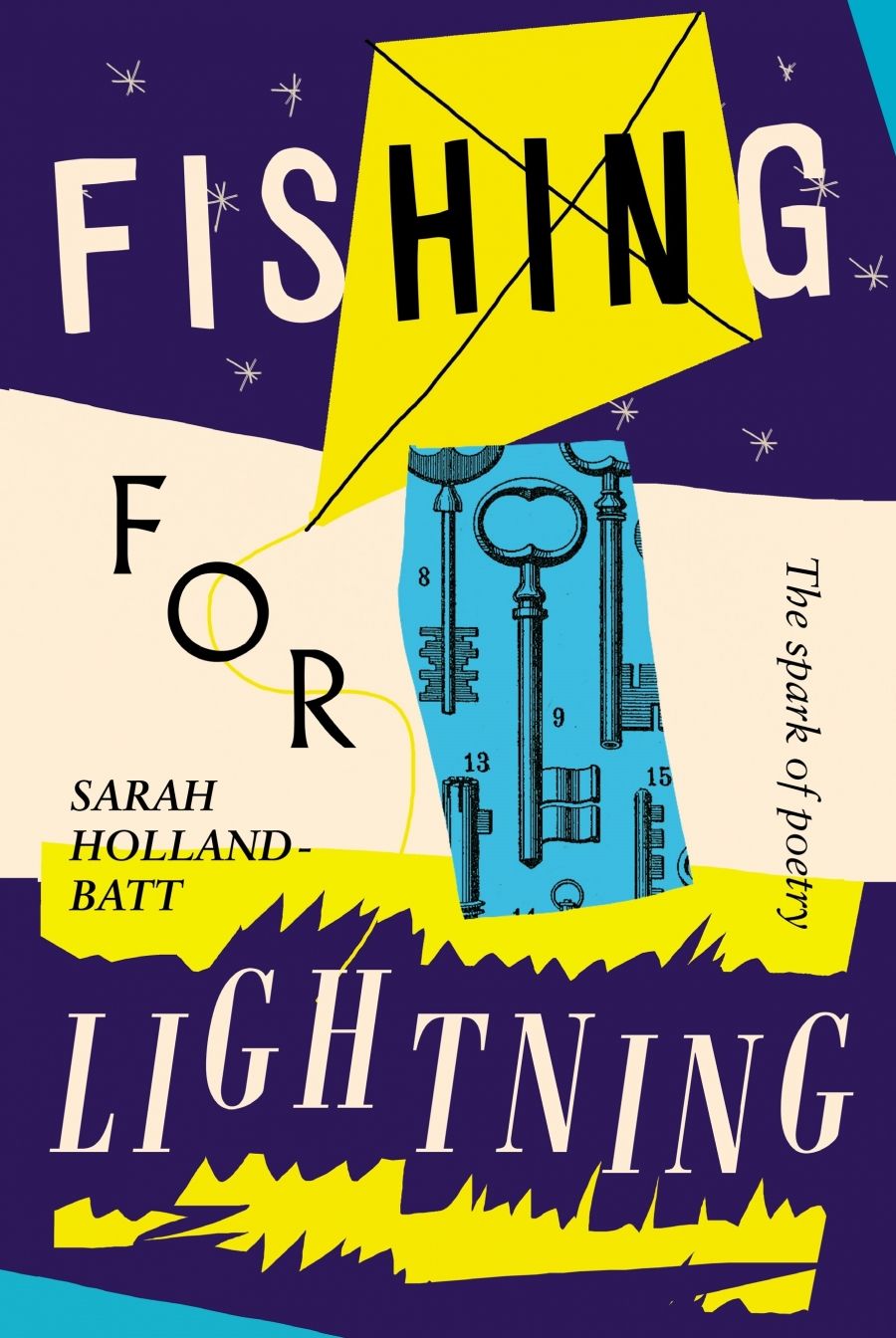

- Book 1 Title: Fishing for Lightning

- Book 1 Subtitle: The spark of poetry

- Book 1 Biblio: University of Queensland Press, $29.99 pb, 287 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/MXb36P

Fishing for Lightning brings together the fifty essays that Holland-Batt wrote for her weekly ‘Poet’s Voice’ column in The Weekend Australian, which began in March 2020. Each essay, with a couple of exceptions, focuses on a recent book by an Australian poet, introducing the book and the poet, and including a poem from the collection. For anyone who knows anything about the relationship between poetry, publishing, and the media, this project, and its subsequent publication in book form, is nothing less than miraculous, and it is testament to Holland-Batt’s standing that she realised – with the support of the Judith Neilson Institute – such a venture.

Holland-Batt focuses on poetry collections published in 2019–20, but she occasionally reaches back further, with 2016 being the limit to her retrospective range. She covers a diversity of Australian poets. These include, to choose a random list, Judith Beveridge, Omar Sakr, Robert Adamson, Charmaine Papertalk Green, Aidan Coleman, and Jeanine Leane. As well as single-authored collections, Holland-Batt attends to a few notable anthologies, and, in the week the American poet Louise Glück won the Nobel Prize for Literature, Holland-Batt (who is an expert on Glück’s poetry) wrote a characteristically fine essay on the new laureate.

Holland-Batt borrows the title of her book from Benjamin Franklin (he of the kite and key), stating in the book’s introduction that she always thought fishing for lightning – an absurd, eccentric, original, rebellious, secretly joyous act – is a perfect metaphor for what readers of poetry do. To outsiders, reading poetry might look like hard work, but when you get the hang of it, it is exhilarating. As a form, poetry is full of freedom and possibility.

‘Freedom and possibility’ are key terms in the pandemic year of 2020–21, with its lockdowns and hard borders. Unsurprisingly then, as Holland-Batt also notes, the essays ‘are a portrait of a year of reading, and a sort of time capsule, too. Where I could, I tried to choose poems or books that reflected the time of year, or events in the news – seeking to show readers that poetry can help us make sense of the times we live in.’

Using poetry, an ancient form as Holland-Batt reminds us, to understand the present day gives the essay collection a dual-facing perspective that is felt in other ways. For instance, in addition to focusing on our current national poetry, Holland-Batt emphasises the transhistorical, transnational, and transcultural nature of poetry. In discussing contemporary Australian poets, Holland-Batt moves freely across time and place, covering everyone from Sappho to Ted Berrigan, John Donne to the Oulipo group. Similarly, Holland-Batt ranges widely over the formal and conceptual landscape of poetry. Her essay on Judith Bishop covers the sonnet, her essay on Jill Jones covers the ode, and so on. Fishing for Lightning, then, is both a snapshot of poetry today in this country, and a superb primer on poetry itself. In addition to being an expert in her field, Holland-Batt is often epigrammatic and funny. While never obscure, she sometimes shows her own love of language, peppering her prose with the odd word like ‘pelagic’ and ‘disjecta’.

As these words might suggest, Holland-Batt is especially good on the sonic condition of poetry. Her essay on ‘Sound and Meter’ – which fittingly concerns that marvellously sonic poet Felicity Plunkett – demonstrates how something as apparently dry as poetic meter can be made intensely interesting. Holland-Batt’s skill with ‘soundy’ poems such as Plunkett’s ‘Syzygy’ (the title of which is nicely explicated) can be seen elsewhere in Fishing for Lightning, such as in her discussion of Stuart Cooke’s ‘kind of recitation of bird names from the poem “Lake Mungo” that serves as a charm, affirming the beautiful biodiversity of the Australian bush, but also as a warning’.

As this observation illustrates, Holland-Batt skilfully balances the formalist and playful aspects of poetry with its ideological and mimetic functions. In doing so, Holland-Batt brilliantly dispels the idea that poetry is merely an expression of affect or subjectivity or identity. All of those things come into play, of course, but they are instruments that need to be animated by the electrical currents of linguistic play, form, genre, and so on.

As her piece on Cooke may suggest, Holland-Batt is perhaps most compelling when dealing with poetry most different from the kind she herself writes. Her essays on Toby Fitch and Michael Farrell are highlights of the book, drawing attention – in the case of the former poet – to poetry’s intense engagement with contemporary modes of communicating through ‘endlessly replicated memes, GIFs, emojis and reposts’. Poetry has always, of course, been reliant on the limitless creative effects of repetition, and Holland-Batt is particularly attuned to this fact. It is perhaps appropriate then that, for me at least, the most exciting essay in Fishing for Lightning is on Jaya Savige’s stunning poem ‘Her Late Hand’. Evoking Keats’s ‘This Living Hand’ (allusion being another form of repetition), Savige’s poem works with the generative power of the anagram, also something – as Holland-Batt points out – with links to ancient poetry. ‘Her Late Hand’ recombines the word ‘handwriting’ nineteen times, to produce end words that Savige incorporates into his elegy with staggering inventiveness. Reading this, alongside Holland-Batt’s insightful account of the poem, shows just how fruitful the conversation between poet and critic can be. It also demonstrates definitively that affective power and formal playfulness are not mutually exclusive things in poetry. Australian poetry and criticism don’t get much better than this.

As Holland-Batt notes in the acknowledgments, the essays in Fishing for Lightning were written in the weeks and months after her father’s death. In the final essay of the collection, Holland-Batt writes that, ‘Since I started this column, I have heard from many readers who found some solace in poetry during the upheavals of the past year’. One of those readers sent Holland-Batt poems by his late son, Andrew Hardy, who passed away in 1997, aged twenty-two. The poem by Hardy that Holland-Batt includes and discusses is a fine one, and her reading of it is characteristically insightful.

The notes of loss, dialogue, and generosity are not ones we naturally associate with works of literary criticism. Through its humane attention to the words of others, Fishing for Lightning is ultimately, and perhaps surprisingly for those unfamiliar with poetry, as moving as it is illuminating.

Comments powered by CComment