- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Memoir

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: An academic cosmopolitan

- Article Subtitle: Amartya Sen’s places of learning

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

By any measure, Amartya Sen’s academic career has been a glittering one. A professor of economics at Harvard University for more than three decades, Sen has also held appointments at Cambridge University, Oxford University, the Delhi School of Economics, and Jadavpur University. In 1998, he was awarded a Nobel Prize for his contribution to welfare economics, including work on social choice, welfare measurement, and poverty. The same year, he was appointed as the Master of Trinity College, Cambridge (the first Asian head of an Oxbridge college). He has also written extensively on economics, philosophy, and Indian society and culture.

- Article Hero Image (920px wide):

- Article Hero Image Caption: The Indian economist and philosopher Amartya Sen (Agence Opale/Alamy)

- Alt Tag (Article Hero Image): The Indian economist and philosopher Amartya Sen (Agence Opale/Alamy)

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Varun Ghosh reviews 'Home in the World: A memoir' by Amartya Sen

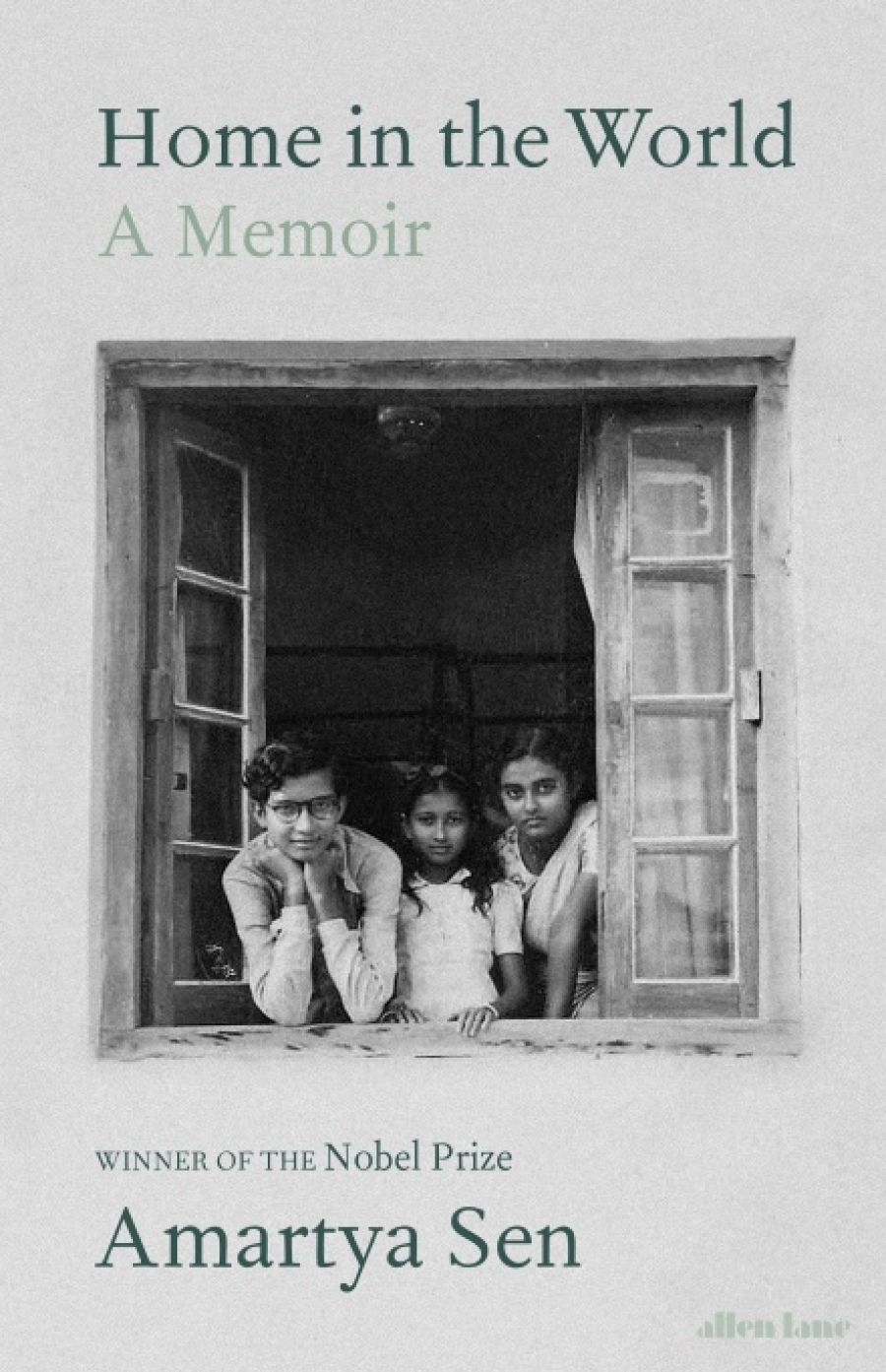

- Book 1 Title: Home in the World

- Book 1 Subtitle: A memoir

- Book 1 Biblio: Allen Lane, $55 hb, 479 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/2rd9xD

Home in the World explores the first thirty years of the author’s life – retracing Sen’s birth in West Bengal in 1933, his studies in India and England, and the early part of his academic career. Subtitled ‘A memoir’, the book is a far less conventional offering in which Sen moves without hesitation between personal reminiscence, history, cultural observation, and political opinion. At its heart, though, Home in the World is about places of learning.

In the early part of the book, Sen paints a captivating picture of his time at Rabindranath Tagore’s progressive school at Santiniketan. Reflecting Tagore’s commitment ‘to avoid sequestering education from human life’, students absorbed a creative and cosmopolitan education outdoors among the trees. As Sen recalls:

Santiniketan was fun in a way I had never imagined a school could be. There was so much freedom in deciding what to do, so many intellectually curious classmates to chat with, so many friendly teachers to approach and ask questions unrelated to the curriculum, and – most importantly – so little enforced discipline and a complete absence of harsh punishment.

The school was also an important cultural and political institution. Tagore himself took part in debates about the future of India, and there was no shortage of prominent visitors during Sen’s time there, including Chiang Kai-Shek, Mahatma Gandhi, and Eleanor Roosevelt. At Santiniketan, Sen developed and pursued a love of Sanskrit and mathematics. He was fascinated by the interaction between abstract reasoning and ‘earthy practical problems’ that would ultimately provide the foundations of his academic work.

At Presidency College in Kolkata, Sen studied economics and mathematics, but it was adda (a Bengali word for an agenda-free discussion on any topic) in the coffee houses and around the College that he loved ‘more than almost any other way of passing time’. He also frequented the ‘constellation of bookshops’ around College Street. Das Gupta’s (established in 1886) allowed the young Amartya to read the new arrivals in the shop and, occasionally, to borrow them overnight. Fatefully, Kenneth Arrow’s Social Choice and Individual Values (1951) was one of them and became critical to Sen’s later work in social choice theory.

While in Kolkata, Sen discovered a small lump in the hard palate of his mouth. Despite two clear diagnoses, the hypochondriacal Sen was convinced it was something more serious. A third review showed that the lump was cancerous and required sustained radiation therapy. Despite a ‘joyful return’ to college life after treatment, this health issue would dog Sen over the years.

After completing his degree in Kolkata, Sen read for a second Bachelor of Arts at Trinity College, Cambridge. Initially, he found friends among the foreign students (many of whom went on to high office and achievement); later his circle broadened to include fellow economists. In Cambridge, as in Kolkata, vibrant and energetic discussion was a priority. In addition to joining various political clubs, Sen was elected to the famous but secretive Cambridge Conversazione Society (known as ‘the Apostles’).

A typical evening would involve a very interesting paper read out by one of the Apostles, followed by discussion, and then there was generally a vote on some thesis linked to what had been read. No one much cared about the outcome of the vote, but the quality of the discussion was a serious concern.

Teaching stints at Jadavpur University in Kolkata, and visiting positions at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and other US universities aside, Sen remained at Trinity until around 1963 before returning to India to teach at the Delhi School of Economics.

Home in the World intersperses the account of Sen’s early career with extended explorations of ideas and matters that spark the author’s interest. Childhood memories of the friendliness of the people in Burma transition into a critique of Aung San Suu Kyi’s policies in relation to the Rohingyas. Fond remembrances of river journeys between Dhaka and Kolkata lead to excursions into the cultural and economic significance of the rivers of Bengal.

Similarly, while in Santiniketan, Sen saw the early signs of what became the Bengal famine of 1943. After a brief description of his experiences, the author embarks on an analysis of the underlying causes of the famine, blaming sharp increases in food demand (and thus food prices) in West Bengal on wartime requirements of British, American, and Indian soldiers stationed there. The result was that many families could not afford to buy food. Technocratic errors and ruthless censorship of reporting on the famine by the British authorities prevented an adequate response to this ‘class-based calamity’. Sen contrasts this with the improvement of overall nutrition in Britain, despite food rationing, during the war.

Economic debates also occupy a large portion of Home in the World. While Sen was at Presidency College, the work of Karl Marx dominated discussion in the academic circles in Kolkata, ideas which Sen then developed by evaluating their merits and limitations. The major arguments between the neo-classical and neo-Keynesian economic schools in Cambridge are described, as are the author’s frustrations with the narrow (and rivalrous) nature of those debates. An entire chapter explores the theories and work of three Cambridge economists who influenced the author: Maurice Dobb, Piero Sraffa, and Dennis Robertson. Aspects of this economic history are engaging, but not always accessible to a non-specialist.

Given the breadth of terrain covered, and the descriptions of various ideas, friends, and institutions, the portrait of Sen himself that emerges seems incomplete. Fleeting references aside, Sen’s adult family life forms no part of the book. The reader learns in passing that the author married his first wife in 1960, divorced her in 1973, and that ‘they had two wonderful daughters’. The book is almost devoid of introspection or any serious exploration of Sen’s emotional (as distinct from purely intellectual) responses to the events in his life. Further, the book’s focus on Sen’s time at elite schools and universities in India, the United Kingdom, and the United States sits uneasily with the subject matter of his research – welfare economics, poverty, and inequality.

Home in the World is a loving ode to Sen’s education, academic experiences, and intellectual friendships. Parts of the book are compelling. However, regular digressions into tangential (and often esoteric) subject matter will limit the readability of the book and leave the picture of Amartya Sen himself largely unfinished.

Comments powered by CComment