- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Politics

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: The Awkward Squad

- Article Subtitle: Barry Jones goes into battle

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Barry Jones is a proud member of the Awkward Squad, one who follows his own convictions rather than the exigencies of day-to-day government. He confesses that in Parliament, ‘I was always aiming for objectives that were seen as beyond the reach of conventional politics’. The memo about ‘the art of the possible’ clearly never reached Jones’s desk. His time as a minister between 1983 and 1990 was a strain for both him and the then prime minister, Bob Hawke. Jones recounts with some glee that Hawke once referred to him as ‘Barry Fucking Jones’.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Paul Morgan reviews 'What Is to Be Done: Political engagement and saving the planet' by Barry Jones

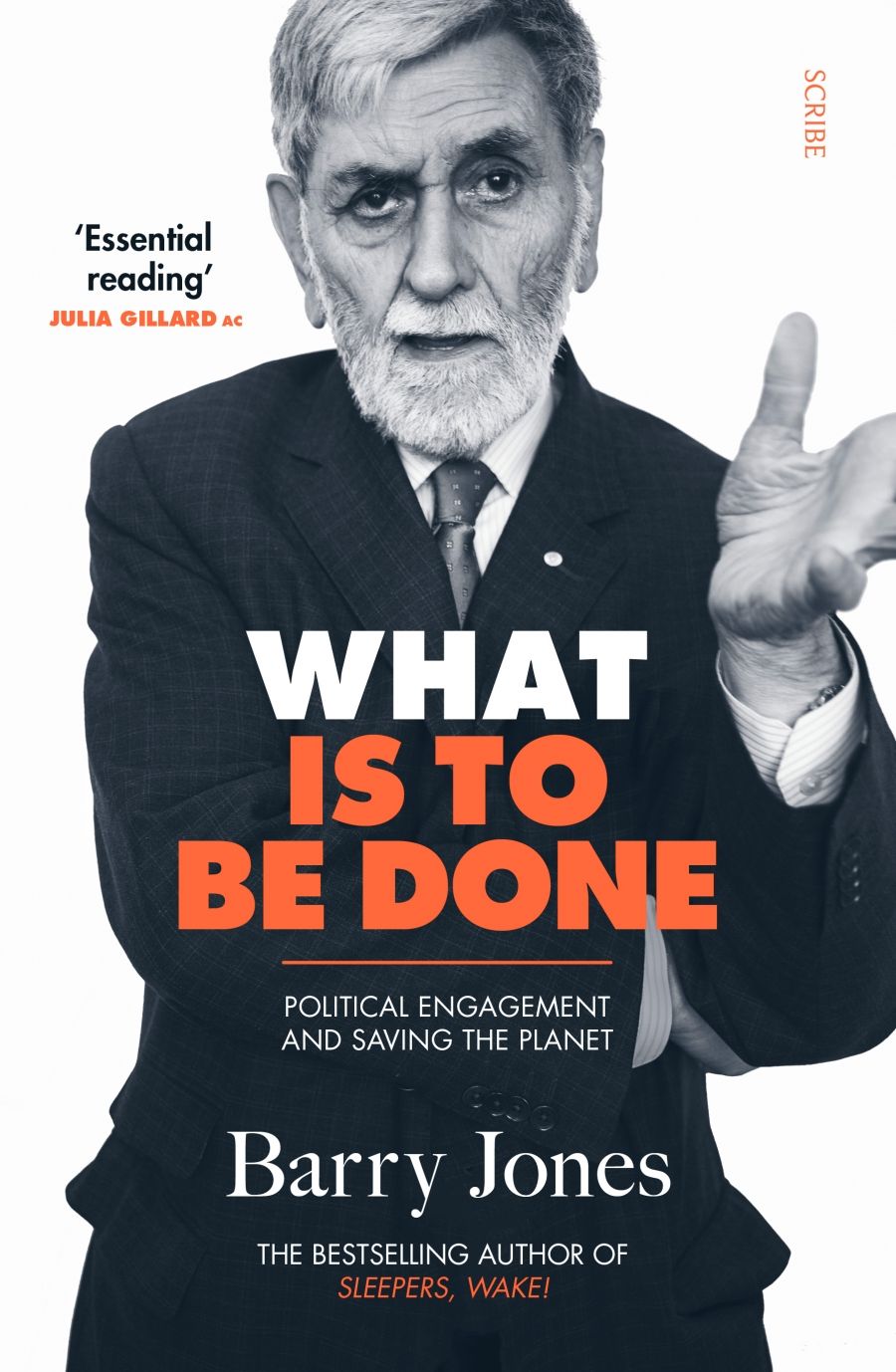

- Book 1 Title: What Is to Be Done

- Book 1 Subtitle: Political engagement and saving the planet

- Book 1 Biblio: Scribe Publishing, $34.95 pb, 389 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/6bE5rN

In What Is to Be Done, Jones turns his attention to contemporary challenges, primarily the climate emergency, threats to liberalism, and the retreat of social democracy as a political force (plus the coronavirus pandemic as a bonus). These are big issues to tackle in a single book, but Jones is up the task. His title is borrowed from a nineteenth-century Russian work by the nihilist revolutionary Nikolay Chernyshevsky. Published in 1863, that book has been described as the worst novel ever written – Vladimir Nabokov eviscerated it mercilessly in The Gift – and also the most influential political text of the century. It was a favourite of both Lenin and Ayn Rand, which probably says all one needs to know about it.

If you want facts, Barry Jones is your man. Names, dates, and titbits of information jump off every page. This is both the strength and the weakness of What Is to Be Done. The issues raised in Sleepers, Wake! were news to most people, and the solutions proposed were radical and challenging. In What Is to Be Done, on the other hand, the concerns discussed and potential solutions are wearyingly familiar. (How many thousand words have you read in the last seven days about the pandemic, the decline of liberal culture, the warming of the planet, etc?) This familiarity diminishes the novelty and power of Jones’s book as a call to arms. Rather than a polemic, it works better as a primer on these critical issues.

Jones is a born educator, with the ability to marshal a complex array of facts and present them clearly and enthusiastically. Information on the threats to liberal democracy and the Covid-19 pandemic is presented with encyclopedic detail. A section on the challenges of the digital age includes a history of the computer beginning with the Sumerian abacus in 2700 BCE. This accumulation of facts, though at times fascinating, threatens to swamp the arguments that Jones is attempting to make. The well-known histories of companies such as Apple, Microsoft, and Google (complete with their founders’ birth dates) take up pages that might have been expended on less familiar research. An example is the sociologist William Davies’ thesis in Nervous States (2018) that voters for Brexit and Donald Trump were motivated by a combination of two factors: hostility to immigration and physical pain. Jones quotes Davies to the effect that around a third of the US and UK populations experience chronic pain. These are often older, poorer, and less healthy people who consequently feel unhappy and angry, and disposed to express this through the ballot box. Chronic opioid use has been found to correlate closely with counties that voted strongly for Trump. The association may be over-simple, but it bears examination. It would have been interesting to read more on this intriguing hypothesis.

What Is to Be Done is most interesting when Jones examines the world he knows best: politics. With experience as a state and federal member, minister, and as a two-stint national president of the ALP, he knows whereof he speaks and doesn’t hold back. The major parties are ‘small, closed, secretive, and oligarchic, and they prefer it that way,’ he writes. They are timid followers of opinion polling rather than political movements with bold policies. The atmosphere in Parliament House is toxic, and tension in the party rooms resembles ‘the shower scene in Psycho’. The lack of serious debate is exacerbated, Jones writes, because Australia has the shortest number of sitting days of any parliament in a democracy: a mere sixty-seven days, around half that of Canada or the United Kingdom. The Labor Party comes in for the most excoriating criticism because Jones cares about it most. Finding someone from a blue-collar background at national conference these days is as likely as finding a platypus there, Jones complains. The ALP especially, he writes, is controlled by self-serving factions of careerists that effectively operate as ‘executive placement agencies’.

Jones confesses to frustration with politics, but his ebullient, hopeful spirit shows through in the final chapter of What Is to Be Done. Australians should engage with politics more, he suggests. It is only this broad public engagement that will bring about positive moral choices on (inter alia) moving to a post-carbon economy, rejecting racism and fundamentalism, and supporting progressive taxation and an updated Constitution. And so say all of us. Barry Jones can be idealistic, even naïve. But he is often right.

Comments powered by CComment