- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: History

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: The pull of Paris

- Article Subtitle: Colonial Australia’s antidote to England

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

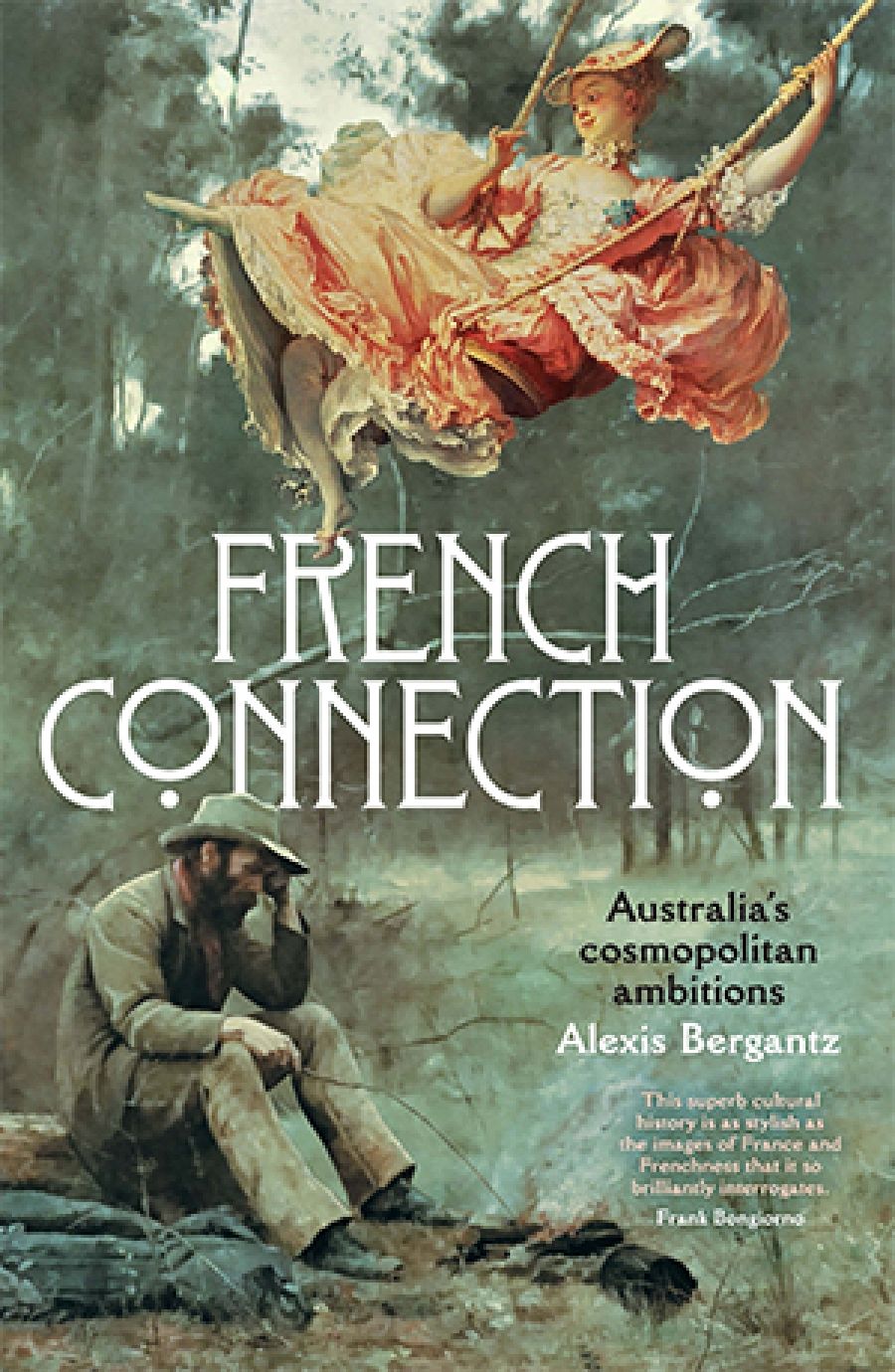

While France provided a relative trickle of immigrants – the French in Australia numbered only four thousand at the end of the nineteenth century – its influence in Australia was surprisingly pervasive. Some years ago, an exhibition entitled The French Presence in Victoria 1800–1901 drew together an extraordinary range of materials, including French opera libretti and school textbooks printed here, together with original Marseille tiles and sumptuous fabrics. But Alexis Bergantz’s new book, French Connection, is not concerned with the spread, or penetration, of French goods. Rather, it is a careful examination of the idea of France. It is typical of its verve and elegance that the cover captures this nicely: Fragonard’s frilly beauty swings high at the top, a world away from the bottom-left corner, where Frederick McCubbin’s bushman sits Down on His Luck. (Tom Roberts got it in one: his well-known painting of Bourke Street includes the French tricolor, flapping from a shopfront.)

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Jim Davidson reviews 'French Connection: Australia’s cosmopolitan ambitions' by Alexis Bergantz

- Book 1 Title: French Connection

- Book 1 Subtitle: Australia’s cosmopolitan ambitions

- Book 1 Biblio: NewSouth, $34.99 pb, 208 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/Eayv42

There was always ambivalence about France, and Bergantz is peculiarly well placed to trace it. He grew up in Alsace, a region sometimes regarded in France as peopled by French-speaking Germans. Later, he was an exchange student in England, and was surprised to encounter condescension there: for some people, France seemed to remain the ‘sweet enemy’. Traditionally it had been so enticing, with its café life, its luxuries, its permissive sexual mores, plus its leadership in the arts. But the French were also seen, when compared with ‘masculine’ England, as a ‘feminine’ country (despite Napoleon), full of excitable, histrionic people, given to political excess, teetering on the edge of social and moral corruption. Some of these attitudes, in an etiolated form, were transported to Australia. In addition, there was the threat posed by the French presence in the Pacific. Sydney built Fort Denison (Pinchgut) as much in response to them as to anyone.

Bergantz himself would find Australian attitudes to the French far more open than the English, and he demonstrates why. In the nineteenth century, Paris was strikingly cosmopolitan: although the number of foreigners (seven per cent) now seems extraordinarily low, this still comprised three times as many as then lived in London, Berlin, or Vienna. Christina Stead would later describe Paris as ‘not so much … the French capital, as the capital of the modern world’. There were some Australian artists who exhibited in its salons, bohemians who loitered in its cafes, and upper-class gels sent to its finishing schools (polishing their manners and ‘filly French’, as Nettie Palmer termed it). There was a view that French-derived culture would add seasoning to the roast beef of old England, helping materialistic colonies to become a cosmopolitan nation-in-the-making. It is quite indicative that J.F. Archibald, the Warrnambool boy who became the founding editor of the Bulletin, was not only a Francophile but also changed his first names to Jules-François.

But it was not all plain sailing. The Alliance Française had no sooner established a branch in Melbourne than it was riven by faction. Women dominated it, in particular Australian women, for whom French was an adornment, essentially a marker of class distinction. Increasingly opposing them was the French consul, who saw the Alliance as a nexus for the whole French community and as a projection of French soft power. But Melbourne’s society ladies saw it basically as one of their enclaves; their idea of French culture was as something disembodied and global, existing outside of France. They even discouraged highly qualified people from lecturing, and made a mess of language examinations. Things came to such a pass that there was a mass walk-out at a meeting addressed by the consul. Not long after, strings were pulled in Paris, with the result that the consul was recalled.

Part of the fastidiousness of the Melbourne Alliance arose from the fact that New Caledonia, annexed by France in 1853, became a penal settlement. Fresh transports kept arriving there almost to the end of the century. For their part – a prefiguration of their attitude to asylum seekers – Australians did not want a bar of it. Apart from having ambitions of their own in the Pacific, they were highly sensitive about their own convict past. (And, until 1868, boatloads of convicts kept arriving in Western Australia.) Drastic exclusionary measures were introduced in, but did not pass, the parliaments in the eastern colonies. There was much talk of ‘the scum of France’, highly exaggerated as (apart from some political prisoners) most of the recidivists had committed minor larceny or had been vagrants. A Victorian premier once argued for a total ban on French migration to put an end to the problem. For it was less one of escapees than of people who had served their sentences and then slipped into Australian colonial society undetected. (One resourceful gent in North Queensland managed to masquerade as a baron, for a long time fooling even his descendants.) In fact, the numbers involved were small and would have amounted to little more than a few hundred.

While French Connection is focused on the nineteenth century, there is an important epilogue on the connection in the twentieth century. There are some surprises: French high fashion remained influential for much of the period, and while there was some austerity just after World War II, Christian Dior himself was aware that Australia afforded his largest market after Paris and New York. (The Sydney store David Jones held the first Dior-only fashion show outside Paris.) When the magnetism of Parisian high fashion began to wane, Australians ‘went crazy for French cuisine’, as Bergantz remarks. In the past twenty years, no fewer than forty books have been produced in Australia about living in France, nearly all by female authors for a female readership. Haute cuisine and haute couture figure in them strongly, along with lingering ideas of distinction.

There are omissions. There is no hint given of the way France also acted as a beacon for the left, particularly after the Paris Commune. Until the Bolshevik Revolution, socialists (even here) still regarded France as the pacesetter. Mention is made of the attempt to make a Parisian boulevard of William Street, Sydney, but not of Melbourne’s four realisations, which include St Kilda Road. Most surprising of all is the failure to mention Louise Hanson-Dyer, whose interest in French music led her to Paris, where she published early music and issued pioneering recordings – on a label that acknowledged the Australian connection in its name, Oiseau-Lyre (Lyrebird). Before she went, Hanson-Dyer also managed to combine, at the Melbourne Alliance Française, the serious with the social. Melbourne University Press thought her worth a full biography in 1994; modesty (almost) forbids me to say I wrote it.

Nonetheless, French Connection is an exemplary piece of cultural history – assiduously researched, written with flair and a lightness of touch. Except in retaining its thorough documentation, the book has thrown off its origins in a doctorate. Alexis Bergantz is now a lecturer at RMIT, and we can look forward to his next book, on Australian links with New Caledonia.

Comments powered by CComment