- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Our code-red present

- Article Subtitle: Keeping score of planetary suffering

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

In August of this year, when the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s Sixth Assessment Report was published, the UN Secretary General, António Guterres, described its findings as ‘code red for humanity’. For those of us working in climate change communication, the alarm was familiar, another scream into the void to punctuate the prevailing astonishment at a world so insouciant in the face of its imminent environmental collapse. The aptly titled Bewilderment, Richard Powers’ first book since his Pulitzer Prize-winning The Overstory (2018), examines our code-red present with unnerving clarity, testing the viability of human life on this planet. As with The Overstory, a novel to which Bewilderment is very much a companion, humankind is on trial. Even by the gruelling standards of Anthropocene literature, it makes for unsettling reading.

- Article Hero Image (920px wide):

- Article Hero Image Caption: The American novelist Richard Powers (photograph by Pako Mera/Alamy)

- Alt Tag (Article Hero Image): The American novelist Richard Powers (photograph by Pako Mera/Alamy)

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): J.R. Burgmann reviews 'Bewilderment' by Richard Powers

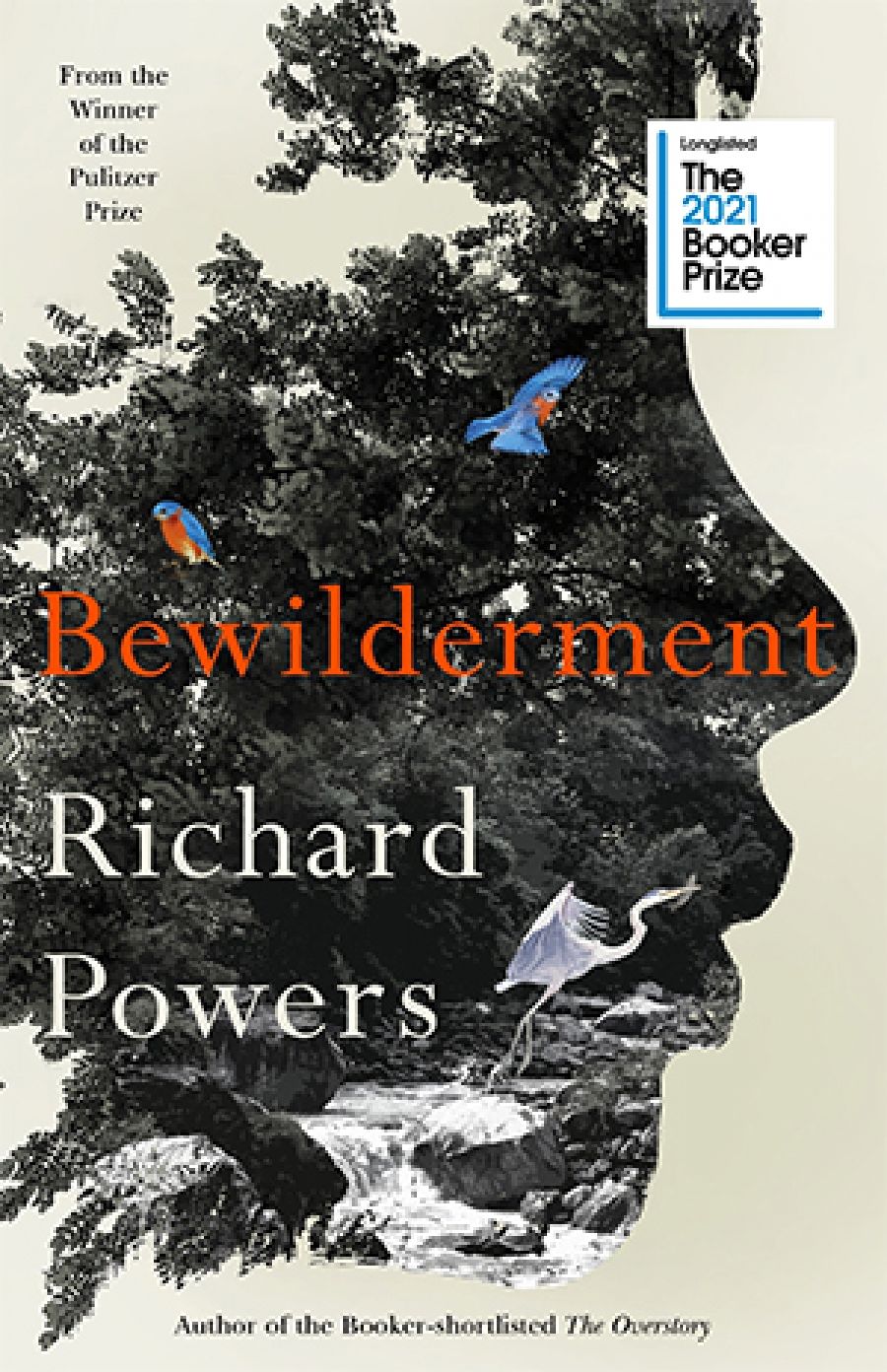

- Book 1 Title: Bewilderment

- Book 1 Biblio: William Heinemann, $32.99 pb, 278 pp

Readers and scholars of the American novelist will undoubtedly note the ecological shift in his two most recent books, a trend that can be observed across the narrative arts more generally, although perhaps not to a sufficiently significant degree given the progress towards ‘the destruction of life on Earth’. The Midwesterner’s concerted turn towards the planetary, which can also be witnessed in writers such as Margaret Atwood, James Bradley, and Kim Stanley Robinson, seems as unlikely to fade as the carbon dioxide levels in our atmosphere. But Powers’ approach to the ‘rising flood of our own craziness’ is distinctive for the way it responds to Robinson’s particular concerns about the limits of representing climate change in fiction:

[T]he phrase ‘climate change’ is an attempt to narrate the ecological situation. We use the term now as a synecdoche to stand for the totality of our damage to the biosphere, which is much bigger than mere climate change, more like a potential mass extinction event.

As in The Overstory, direct reference to ‘climate change’ appears rarely, if at all, throughout Bewilderment. In resisting nomenclature and eschewing expository shorthand, Powers commits quite radically, even riskily, to specifying the horrors from which such terms normally shield the reader.

Narrator Theo Byrne, recently widowed, is an astrobiologist who has developed a method to search for life on other planets. His life in Wisconsin now revolves around his only son, Robin (‘Robbie’), a capricious yet creative and preternaturally sensitive nine-year-old with a neurodivergent diagnosis about which his father is sceptical:

When a condition gets three different names over as many decades … two subcategories to account for completely contradictory symptoms, when it goes from nonexistent to the country’s most commonly diagnosed childhood disorder in … one generation, when two different physicians want to prescribe three different medications, there’s something wrong.

Struggling with school and still mourning the sudden loss of his mother, Alyssa, a once-prominent environmental lawyer and activist, Robin grows increasingly drawn to the natural world. When Robin faces expulsion in the wake of a schoolground altercation, Theo is confronted with the prospect of putting his son on psychoactive medication. Through his campus networks at Madison, he seeks recourse in an experimental, non-invasive neurofeedback trial – an earlier iteration of which he and ‘Aly’ had taken part in prior to her death – to train Robin ‘how to attend to and control his feelings, the same way behavioural therapy does, only with an instant, visible scorecard’. Robin turns out to be a ‘high-performing trainee’, suddenly able to regulate his emotions. His empathy blossoms to otherworldly heights, eerily akin, in Theo’s mind, to that of the child’s brilliant mother, who could feel ‘what was really happening on the planet, the systems of invisible suffering on unimaginable scales’.

Robin’s elevated sensitivity – a narrative ploy that recalls protagonist Thassa Amzwar from Powers’ novel Generosity: An enhancement (2009) – underscores an aporia that echoes throughout Bewilderment, that of how to explain ‘the world’s basic brokenness’ to your child, especially when ‘more empathy meant deeper suffering’. Theo offers escape in the form of wild speculations, narrative explorations of life forms on the distant planets of his life’s work, which Powers renders in self-contained chapters interspersed throughout the novel. But this imaginative fortress can only withstand so much. Their broken world is recognisably our own, populated as it is with blunt analogues: a despotic, election-rigging president who tweets nonsense to the masses – ‘America, have a look at today’s ECONOMIC numbers! Absolutely INCREDULOUS! Together, we will stop the LIES, SILENCE the nay-sayers, and DEFEAT defeatism!!!’; alt-right militias take to the streets; zoonotic viruses spill over from congested livestock into human populations; a platform resembling TED called COG is ‘the chief way that most of the world learned about scientific research … in less than five minutes’; and a Swiss climate activist named Inga Alder, ‘the world’s most famous fourteen-year-old’, shames ‘the Council of the European Union into meeting the emissions reductions they had long ago promised’. Entranced by this ersatz Greta Thunberg, who ‘called her autism her special asset’, Robin starts up his own sincere campaign to save the planet – or, more specifically, endangered species – with the aid of his talent for visual art.

Time, predictably, is running out. Ice shelves break off from Antarctica, temperatures rise, and extreme weather events multiply, while the ‘heads of states … [test] the outermost limits of public gullibility’. The latter portion of the novel bears an escalating sense of chaos, both personal and planetary, taking turns toward an end that, like our unfolding climate catastrophe (if you’ll excuse the dalliance here with nomenclature), seems tragically inevitable. Through a delicate sequence of narrative manoeuvres, Powers manages to align the ‘small’ stakes of a few people – Theo and Robin – with the ‘vaster catastrophe’ besetting the planet. Even Bewilderment’s larger, flashier counterpart The Overstory is self-referentially puzzled by this narrative demand: ‘the world is failing precisely because no novel can make the contest for the world seem as compelling as the struggles between a few lost people’.

It is tempting to frame Bewilderment as a response to, or inversion of, The Overstory’s perceived misanthropy. To do so would be to overlook an undercurrent of humanism manifest throughout Powers’ oeuvre. Rather, his recent project has centred on recalibrating frames of reference. If The Overstory implored us to consider time ‘at the speed of wood’, then Bewilderment redirects our gaze out into space, to look back and see our ‘changing world’ as a great cosmic improbability ‘that by every calculation ought never to have been’. And from these spacetime coordinates we might arrive at the same conclusion as Theo, that ‘there [is] no stranger place than here’. It should leave us bewildered enough to demand, as Robin does, a ‘new planet, please’.

Comments powered by CComment