- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Giving breath to the ghosts

- Article Subtitle: A mood of systematic retrospection

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Nicolas Rothwell is perhaps best known as a critic of art and culture for The Australian, though he has also published several non-fiction books, one of which, Quicksilver, won a Prime Minister’s Literary Award in 2016. Red Heaven, subtitled a ‘fiction’, is only the second of Rothwell’s books not to be classified as non-fiction. Always straddling the boundary between different genres, Rothwell has cited in Quicksilver Les Murray’s similar defence of generic hybridity in Australia: the novel ‘may not be the best or only form which extended prose fiction here requires’. Working from northern Australia, and intent upon exploring how landscape interacts obliquely with established social customs, Rothwell, in his narratives, consistently fractures traditional fictional forms so as to realign the conventional world of human society with more enigmatic temporal and spatial dimensions.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Paul Giles reviews 'Red Heaven: A fiction' by Nicolas Rothwell

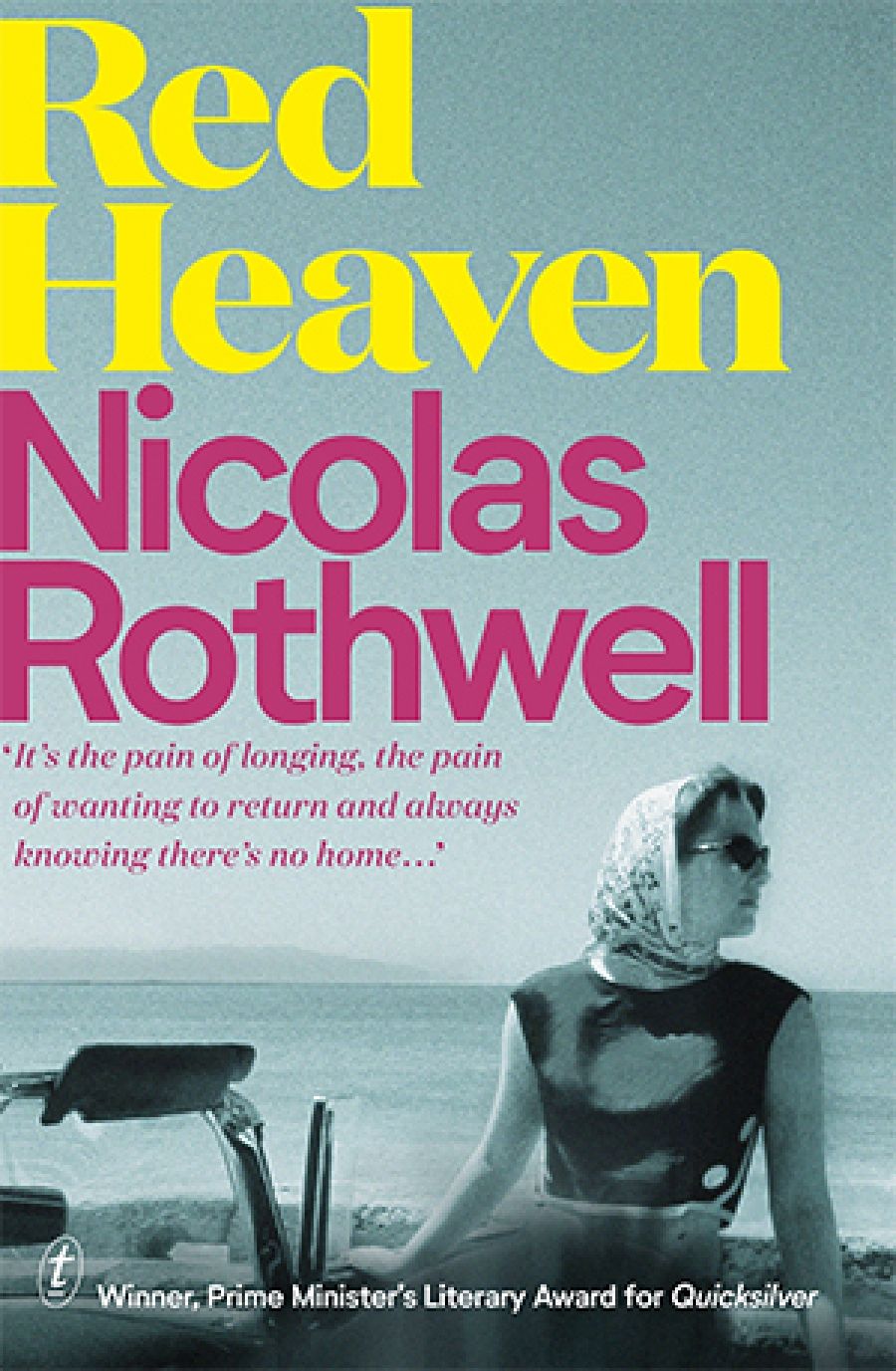

- Book 1 Title: Red Heaven

- Book 1 Subtitle: A fiction

- Book 1 Biblio: Text Publishing, $32.99 pb, 378 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/e4NPLz

Red Heaven, set mainly in Europe, tells the story of how a boy growing up is deeply influenced by two women he calls his ‘aunts’. Serghiana, the ‘red princess’, is the daughter of a Soviet general in the communist regime who goes on to work as a film producer in California; Madame Ady, described as ‘a gentler kind of autocrat’, is a fashionable Viennese woman married to a famous conductor and attracted to life’s glittering surfaces. The boy at the centre of this book remains unnamed, with the narrative focusing upon how these women have shaped his life. The time frame jumps backwards and forwards to exemplify the book’s thesis about life involving a series of repetitions, ‘pattern not coincidence’. As Serghiana’s production assistant puts it, ‘we’re all trapped, every one of us – we’re in a cycle, going round and round the same life all the time’. Such a pronouncement at any social gathering would surely be a conversation stopper, and the dialogue here tends towards the philosophical rather than the colloquial, just as the characterisation is based on type rather than haphazard contingency. This is a fiction of ideas, one of Rothwell’s key notions being that any conception of progress is illusory. As one of the characters says: ‘these people live through the wounds of the past … they go forward looking back.’

Rothwell has observed in an interview that Red Heaven is marked by figures who are absences rather than presences. The boy’s mother, for example, is a notable absentee, her relation to his aunts hinted at but never addressed directly. Another spectre that haunts the book only obliquely is a second meaning of ‘red’, which here indirectly implies not only the ‘Red Princess’ of a communist aristocracy, but also the Australian Red Desert, about which Rothwell has written many times. (The first section of Quicksilver is entitled ‘Into the Red’.) Serghiana in California wishes to ‘make a bridge between two worlds – between two systems’, and Rothwell’s narrative similarly attempts to bridge the discursive worlds of Europe and Australia, contemplating ways in which the scrambled time frames of the Australian Red Desert might work as a template for the human world more generally. Quicksilver, which is set in the Northern Territory, considers ‘the part in the history of ideas played by this continent’, and Red Heaven develops this ambitious conception in imaginative terms, with the narrator meditating on how ‘the past was still present there for me: as if it was claiming me and calling me’.

In relation to the history of ideas, Red Heaven offers a compelling and original treatment of the circuitous ways in which temporal sequence operates. In this specific work, however, such an imaginative conceit does lead to some awkward technical issues, since the narrator becomes a shadowy, passive figure whose fate is determined by his past rather than by his actions and engagements in the present. The repeated emphasis here on telling ‘stories’ evokes a mood of systematic retrospection, with the book structured around a series of soliloquies rather than any dramatic interaction where an exchange of views might make a positive difference to the characters. For Rothwell, fiction exemplifies a state of revelation, the elucidation of something that already exists, rather than a representation of social contact or conflict leading to a potentially different future. As Madame Serghiana puts it, you reach a ‘point where truth is shown to you – and everything after that is epilogue’.

Some of Red Heaven’s most effective passages involve critical meditations on other books, works of art, or films. There is an exquisite description of how the Sistine Madonna at the Pushkin Museum in Moscow impacted upon Dostoevsky, and a commentary on how all of the films by Russian director Andrei Tarkovsky involve ‘a quest for the divine in life’. In fact, Rothwell’s prose is reminiscent in its palimpsestic style of Tarkovsky’s cinematic effects, superimposing a frame of memory on visual scenes and landscapes as a way to invoke a shifting, evanescent mode of transcendence, where mind and matter both complement and contradict each other. Rothwell is particularly interested in the way Dostoevsky’s obsession with the Sistine Madonna re-echoes throughout his subsequent writings, and this corroborates his sense of the persistence and recurrence of luminous epiphanies, even in partial or fragmented form. Rothwell himself has wide professional and personal experience in the old Soviet Union and Eastern Europe, and this narrative brings places that are distant in both time and space into creative juxtaposition with contemporary concerns.

In the opening pages of Red Heaven, Serghiana recommends to the narrator Madame de Lafayette’s La Princesse de Clèves, and he subsequently comments on how the French author of romance was influenced by her intellectual liaison with the ‘chilly, self-contained’ La Rochefoucauld. Red Heaven nods to this long tradition of the European philosophical novel, while also seeking to integrate it with peculiarly Australian conditions. In Quicksilver, Rothwell praises Bruce Chatwin’s ‘rebellion against standard, sequential forms of narrative’, and Red Heaven follows a similar experimental trajectory. The book ends with the narrator’s friend Blaize telling him: ‘Don’t be a writer who writes everything except the thing that matters. Give breath to the ghosts inside you. Tell the story you know best.’ Abjuring the idea of the novel as a mere social construction, Red Heaven attempts instead to resuscitate ‘ghosts’ buried deep within the narrator’s psyche. Rothwell’s book is almost deliberately frustrating in the way it diminishes any sense of the narrator’s selfhood and evades the kinds of social scenarios and settings to which the novel has more traditionally been drawn. Nevertheless, it is a work of genuine intellectual exploration, original and provocative on its own hermetic terms.

Comments powered by CComment