- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Society

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: The internet of things

- Article Subtitle: What it means to be human

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

In her novel Frankissstein (2019) – a reimagining of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (1818) that embraces robotics, artificial intelligence (AI), and transhumanism – Jeanette Winterson writes, ‘The monster once made cannot be unmade. What will happen to the world has begun.’ This observation might have served as an epigraph for her new book, 12 Bytes. Comprising twelve essays that ruminate on the future of AI and ‘Big Tech’, 12 Bytes contends that looming technological advances will demand not only resistance to the prejudices and inequalities endemic in our current social order, but also a reconsideration of what it means to be human: ‘In the next decade … the internet of things will start the forced evolution and gradual dissolution of Homo sapiens as we know it.’

- Article Hero Image (920px wide):

- Article Hero Image Caption: British author Jeanette Winterson (photograph by Ali Lorestani/Alamy)

- Alt Tag (Article Hero Image): British author Jeanette Winterson (photograph by Ali Lorestani/Alamy)

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Diane Stubbings reviews '12 Bytes: How artificial intelligence will change the way we live and love' by Jeanette Winterson

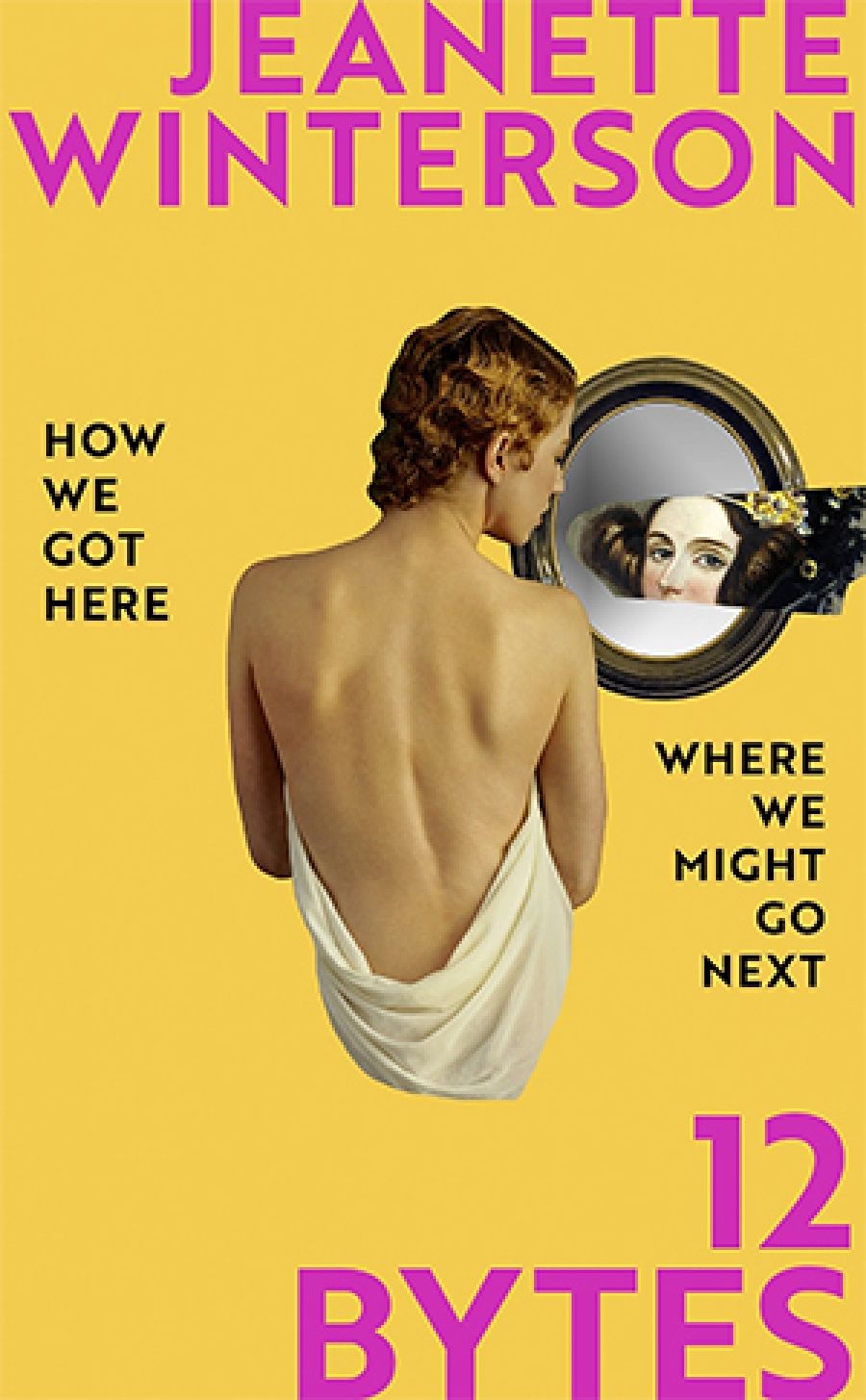

- Book 1 Title: 12 Bytes

- Book 1 Subtitle: How artificial intelligence will change the way we live and love

- Book 1 Biblio: Jonathan Cape, $32.99 pb, 275 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/doGvDM

Persuaded by American futurist Ray Kurzweil’s assertion that progress towards a future where the human species is fully integrated with AI is now irreversible, Winterson set out on a campaign to ‘track the future’, researching the relevant literature – scientific, economic, political, and philosophical – and wandering (often undercover) along both the highways and shadowy back alleys of the internet. 12 Bytes, Winterson’s first essay collection since the radiant Art Objects: Essays on ecstasy and effrontery (1995), is the result of that endeavour.

There is no mistaking Winterson’s fundamental optimism about the future of AI, nor her enthusiasm for the possibilities AI presents for the destiny of both Homo sapiens and the planet. She envisages in AI and artificial general intelligence (AGI) – where AI becomes self-programming and self-replicating – the potential for a society that is predicated on hive-like connections and relatedness, on an ‘interdependent web of livingness’, rather than difference.

Winterson canvasses the ways in which AI will allow us to push the limits of human existence, from interrogating whether human experience demands an embodied engagement with the physical world to examining the practical and existential repercussions of delaying, even defeating, death.

According to Winterson, in order to understand both the ‘Data Age’ and the future of AI, we need first to understand ‘how we arrived where we are now’. She situates the seedbed of AI in the nineteenth-century Industrial Revolution, the idea for Charles Babbage’s Analytical Engine (the first recorded design for a computer) flowing from innovations in weaving technology. As Babbage’s collaborator Ada Lovelace noted, the engine was able to ‘[weave] algebraic patterns just as the Jacquard loom weaves flowers and leaves’.

Winterson’s survey of the evolution of technology also takes in the advent of the transistor (she notes that where the first portable radio had six transistors, the iPhone 12 has 11.8 billion), ambient and integrated computing (devices like Alexa and Siri; internet-enabled fridges and clothing), early mobile phones, WiFi, companion robots, brain–computer interfaces (using thought processes to control AI), bioengineering, and trans- and post-humanism (humans merging with machines and the end of ‘meat-based physicality’).

Passionate as Winterson is about the future that AI promises, she recognises that humanity itself will determine whether this future is utopian or dystopian. ‘What concerns me,’ she writes, ‘is that transforming our biological and evolutionary inheritance … will not, by itself, transform us.’ Situating the expansion of AI within its historical and political contexts, Winterson astutely demonstrates that unless there is the political will to legislate just and equitable guidelines for the expansion of AI, we are doomed to repeat the mistakes of the past.

Drawing on the deleterious impacts of the Industrial Revolution, the sidelining of women in the development of computing, and Big Tech’s modus operandi, Winterson decries the monetisation of privacy, the diminishment of diversity, and the social inequalities and gender biases that technological progress has both initiated and reinforced.

How technology exacerbates existing discriminatory attitudes is illustrated by the emergence of sex-bots (robotic and AI-driven sex dolls). For example, there is the Harmony doll, which allows buyers to choose between ‘42 different nipple colours and 14 labia styles. The vagina self-lubricates, and it detaches for easier cleaning.’ Other dolls are programmed to simulate resistance so that, in Winterson’s words, ‘her owner can simulate rape’.

While acknowledging that sex-bots may have some role to play in breaking down conventional notions of monogamy and sexual relations, Winterson is clear about their dangers, particularly given the way they are regarded in certain corners of the internet, sex-bots becoming ‘a new and nasty way of spreading the age-old disease of misogyny’.

Winterson also reflects on the prejudices that are embedded in the programs that drive Big Tech. Data sets – the information on which the algorithms driving computers are based – are essentially stories, and if those stories ‘are overwhelmingly male-authored and male-centric’, if they privilege existing binaries and biases, and if they fail to reflect the diverse and heterogenous nature of humanity, then our AI-future will simply strengthen those same inequalities and injustices.

There is also the issue of privacy. As Winterson argues, ‘[we] have signed up to levels of surveillance dictators could only dream about – and struggle to enforce. And we’ve done it freely, willingly, actually without noticing, in the name of connectivity and “sharing”.’ Crucially, this information is used to modify our decisions, purchases, and affiliations, controls that, as China’s social credit scores, the 2016 US election, and the 2016 Brexit referendum confirm, can have far-reaching consequences: ‘Give an ideal an algorithm ... and it easily becomes a tool for coercion and control.’

In her fiction, Winterson has frequently positioned herself at the intersection of the arts and sciences, so she is the perfect guide for this journey into the near future. She skips between reference points – ranging from Classical Greece to pop culture – with a nimble intelligence and a conversational, occasionally gossipy style that make these essays immediately accessible. And she has a quick wit: ‘Men invented the geek-gene – and then worshipped it as God-given.’

‘The arts,’ Winterson notes, ‘have always been an imaginative and emotional wrestle with reality’, and that is precisely what she exemplifies in 12 Bytes, richly imagining the possible manifestations of AI and Big Tech that lie ahead in a way that, as in so many of her novels, brings a poetic sensibility to the science: Mary Shelley and Ada Lovelace were ‘flares flung across time, throwing light on the world of the future’; our minds are ‘moving prisms of light’.

12 Bytes asks ‘are we ready’ for what is coming? Do we, as a species, ‘have the emotional intelligence and ethical sobriety to take the next step?’ Winterson seems hopeful that we do. Watching humanity’s dawdling efforts to get ahead of Covid-19 and the climate crisis, I am far less confident.

Comments powered by CComment